When filmmakers turn real-life events into cinematic narratives, they usually take many liberties with the facts. I've never been one to lament this practice or question its necessity. In all cases, boiling down events that took place over years, months, or even weeks into two or three hours requires altering reality in myriad ways. Timelines expand and contract, groups of individuals become fused into a single composite character, the chronology of proceedings gets reordered, and the actual people involved are invariably transformed into more attractive and articulate versions of themselves. In many cases, circumstances are exaggerated, and entire incidents are even invented by filmmakers in order to convey the emotional accuracy of what the real-life protagonists experienced. These changes occur so that a story can be clearly and efficiently told through a simplified dramatic interpretation of an infinitely more complex reality. Without simplification, the truth risks getting buried under too many facts. Without radical embellishments, biographical and historical films would not be able to put across the sensations of wonder, tension, fear, bliss, despair, trauma, or power that the actual participants felt. Audiences would be denied a sensory understanding of the deeds, discoveries, and ordeals a film depicts. Narrative features and even documentaries never show us the unadulterated truth. They present a cinematic exegesis of reality, and moviegoers do themselves a great disservice when they fall into the trap of believing otherwise.

All the President's Men is the closest we get to being the exception that proves the rule about the need for taking extensive artistic liberties when dramatizing a fact-based story for film. The only significant creative license taken by producer Robert Redford, director Alan J. Pakula, and screenwriter William Goldman is what they chose to focus on and what they chose to ignore in their 138-minute film. That the picture didn't just end up a dull procedural, a sanctimonious and slanted history lesson, or an embarrassingly inaccurate construct is due to the talent and diligence of these men, as well as the film's exceptional cast and its gifted cinematographer Gordon Willis. All the President's Men is the most fascinating and inspirational film ever made about journalism, specifically because it never plays fast and loose with its fact-based story, yet still it functions as a riveting and dynamic thriller. Redford, Pakula, and Goldman create drama, tension, suspense, and emotional resonance through their faithful presentation of the facts as discovered by the two protagonists, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. With care, the movie traces how these cub reporters' investigation broke the infamous Watergate story, uncovered the crimes of a corrupt administration, and ultimately led to President Richard Nixon's resignation. By taking a measured and mature approach to this factual tale, the movie remains the gold standard of all films based on real-life events: a rare example of a truly great docudrama.

Released the same year as Network, Sidney Lumet's and Paddy Chayefsky's cynical denouncement of the TV news industry, All the President's Men depicts the most heroic movie journalists this side of Clark Kent. And while Network was dead-on in its predictions about the future of television news (its over-the-top satire now seems tame compared to contemporary reality), All the President's Men looks better and better as a film and as a portrait of journalists. Producer Robert Redford, one of the more politically interested and active members of the Hollywood community, was a passionate follower of the Washington Post's coverage of the ongoing Watergate story. At the time of the break-in at the Democratic headquarters at The Watergate Hotel, Redford was promoting The Candidate, a movie he made with Michael Richie about the cynical behind-the-scenes machinations of political campaigns.  Films about politics were considered a tough sell at the time, so Warner Brothers sent their star Redford on a whistle-stop tour through Florida that mirrored the one taken by actual people running for office. Redford and the studio hoped to ride on the publicity of real-life candidates to drum up interest in their fictional movie. During the tour, Redford met many political journalists who, like him, were following the developing story of the Watergate break-in. These savvy political insiders seemed to think there was far more to the story than the public was led to believe, but when Redford asked why they weren't writing anything about it, they laughed at his naivety. Redford became even more disillusioned with politics on this trip than he already was, but as Woodward and Bernstein's small stories began to develop, he took notice. As fascinated as he was by the details of the articles, the men behind the headlines came to interest him even more. When the two young writers made a critical error in their reporting, the White House denounced them, and they became news themselves. When it later emerged that they were, in fact, on the right track, Redford attempted to meet with them several times.

Films about politics were considered a tough sell at the time, so Warner Brothers sent their star Redford on a whistle-stop tour through Florida that mirrored the one taken by actual people running for office. Redford and the studio hoped to ride on the publicity of real-life candidates to drum up interest in their fictional movie. During the tour, Redford met many political journalists who, like him, were following the developing story of the Watergate break-in. These savvy political insiders seemed to think there was far more to the story than the public was led to believe, but when Redford asked why they weren't writing anything about it, they laughed at his naivety. Redford became even more disillusioned with politics on this trip than he already was, but as Woodward and Bernstein's small stories began to develop, he took notice. As fascinated as he was by the details of the articles, the men behind the headlines came to interest him even more. When the two young writers made a critical error in their reporting, the White House denounced them, and they became news themselves. When it later emerged that they were, in fact, on the right track, Redford attempted to meet with them several times.

It took years before Bob Woodward returned any of Redford's calls, but eventually the actor met with both journalists and learned they were planning to turn the nearly 400 articles they had written into a book. By this point, the term Watergate referred to far more than the break-in at the DNC headquarters; it was a catchall for conspiracy and corruption within the Nixon administration. For years, the importance of the Watergate scandal waxed and waned in the public consciousness, but Redford knew a definitive book by the two men who broke the story would be a best seller, and he wanted to secure the movie rights to whatever they came up with. At the time, Woodward and Bernstein planned to write the story from the perspective of the burglars, but Redford convinced them that they should tell their own tale of how they uncovered their information, worked together, persuaded their nervous editors to publish, and doggedly connected the dots to break what was rapidly becoming the biggest political story of a generation. By the time the book was published on June 15th, 1974, the Senate had begun conducting hearings into Watergate, and major members of the Nixon administration were being indicted, fired, or compelled to resign from their posts. A month after publication, the House Judiciary Committee passed the first article of impeachment against Nixon. It would take two more years before the film All the President's Men would come out, but Redford began working on it when the book was still a collection of notes and articles.

The more he got to know the two writers, the more he saw in his mind the film he wanted to make. They were a classic odd couple: Woodward, a measured, detail-oriented, mainstream Republican WASP from the Midwest; Bernstein, a passionate, intuitive, radical liberal Jew from the East Coast. Redford could see how the individual strengths of these two young men had combined into a powerful force, making them classic underdogs who triumphed over a powerful adversary. By this point, Redford had made The Sting (1973), his second buddy picture with Paul Newman, which was an even bigger hit than their first pairing, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). Redford saw the power in movies about a dynamic duo, but, at this point, he was not thinking about All the President's Men as a major feature starring him, but rather as a small-scale, black-and-white picture that he would produce with a cast of unknown actors.

To turn the book into a screenplay, Redford hired the talented, Oscar-winning writer of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, William Goldman (who went on to a storied career as one of Hollywood's most celebrated screenwriters and script consultants—penning films as diverse as A Bridge Too Far, The Princess Bride, and Misery). The challenge of adapting All the President's Men to film was daunting. The book had almost no narrative structure, little dialogue to draw on, and dozens of obscure names. Goldman didn't see how he'd be able to convey the significance of each person Woodward and Bernstein spoke to, and the way that pieces of information from one source led to another. The genre and subject matter, too, were problems. While Hollywood studios loved to make political thrillers, serious dramas about contemporary politics were considered box-office poison. Then, as the years of work dragged on, Watergate became a subject most Americans grew tired of, thought they knew everything about, and wanted to put behind them. In his astute and entertaining Hollywood memoir Adventures in the Screen Trade, Goldman describes how this screenwriting assignment was a crazy task to take on,  especially because everyone who would eventually review the picture had experience working in a newsroom and therefore would pounce on anything that didn't feel authentic to that milieu. Indeed, that was many people's reaction to Goldman's first draft. He hadn't put in the kind of time Redford had spent visiting newsrooms, hanging out with reporters, and getting the insider's perspective on how the job worked. His greatest contribution to the film was in finding a dramatic structure for the screenplay. Boldly jettisoning the entire second half of the book and concentrating on the mystery and details of the investigation, Goldman used as his climax the one serious error the reporters made, a mistake that almost killed the story, ended their careers, and disgraced the Washington Post. But it was Redford who worked tirelessly with him to get the smaller details correct, so they could make a film that rang true.

especially because everyone who would eventually review the picture had experience working in a newsroom and therefore would pounce on anything that didn't feel authentic to that milieu. Indeed, that was many people's reaction to Goldman's first draft. He hadn't put in the kind of time Redford had spent visiting newsrooms, hanging out with reporters, and getting the insider's perspective on how the job worked. His greatest contribution to the film was in finding a dramatic structure for the screenplay. Boldly jettisoning the entire second half of the book and concentrating on the mystery and details of the investigation, Goldman used as his climax the one serious error the reporters made, a mistake that almost killed the story, ended their careers, and disgraced the Washington Post. But it was Redford who worked tirelessly with him to get the smaller details correct, so they could make a film that rang true.

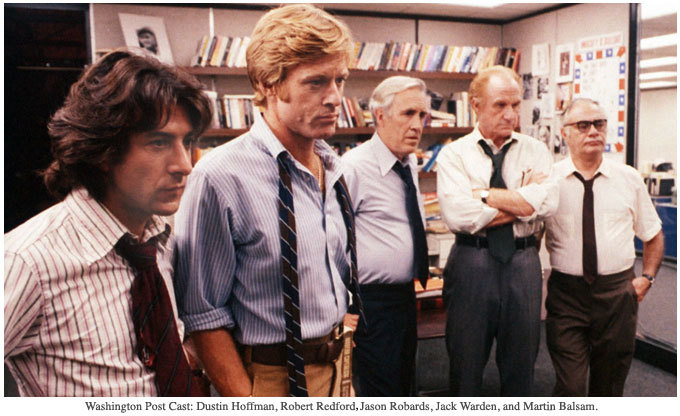

Redford, who was the biggest box-office star in the world at the time, initially did not want to play Woodward, believing it would put too much focus on one member of the duo and unbalance the movie. But Warner Brothers would only give Redford the budget he wanted if he played the lead role. He knew the film would only work if he could cast an actor of equal repute as Bernstein. In 1975, Dustin Hoffman was the only star who fit that bill and was the correct ethnicity- unless you count Al Pacino, who has played quite a few real-life Jewish figures in his day. Hoffman, initially an obscure but exciting off-Broadway stage actor, now risen to the unlikely status of Hollywood megastar via his acclaimed performances in The Graduate, Midnight Cowboy, Little Big Man, Straw Dogs, Papillon, and Lenny, was eager to take on the role. The pairing of Redford and Hoffman, two actors whose looks and approaches to acting couldn't be more different, is ideal and reflects the important stylistic differences between the men they're portraying. It also balances the picture beautifully. They even shared top billing by adopting the procedure Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne used for The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: one name billed over the other in the posters and trailers, with the order reversed in the film's credits. The two actors memorized each other's lines so that they could constantly interrupt, interject, and finish the other character's sentences and thoughts during various takes. This rapid-fire way of speaking adds credibility, intensity, and humor to the relationship between the two journalists and their passionate search for the truth.

Redford worked with Goldman on the various drafts of the script, but when director Alan J. Pakula was hired, even more research and drafts followed. Goldman recounts how Pakula was relentless in requesting rewrites and multiple versions of every scene; wanting all interesting tidbits, as gleaned from fieldwork, to be crammed into the shooting script; and requiring that many options be left open, on set and in the editing room, to give the director the maximum flexibility. Pakula would implore Goldman, "Don't deny me any riches!" But while the length, nuance, and structure of individual scenes constantly changed, everything in the script had to be vetted and confirmed by multiple independent sources, as everyone involved wanted to make the most accurate picture possible. Again, it was Redford, in his role as producer, who followed up on all these details. The film literally began and ended with him. Pakula was a fantastic director, but he wasn't the type of guy to work late into the night, obsessively trying to get everything perfect. That was Redford. When Pakula would knock off around six every evening to have cocktails with friends, Redford would linger in the editing room with Robert L. Wolfe (who also cut several films for Sam Peckinpah, John Milius, and Mark Rydell). Redford oversaw editing the same way he did the screenplay, making sure each scene played as well as it could.

Though Bernstein didn't cooperate much with the filmmakers (he and his future wife, Nora Ephron, wrote their own screenplay, which they hoped would eventually be used when Goldman's first draft disappointed), Woodward and Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee wisely decided to work closely with the filmmakers. They provided all the assistance they could to bring authenticity and integrity to what they assumed would become the definitive version of the story in the public consciousness. Woodward even weighed in on the most sensitive aspect of the narrative, the identity of the secret informant known as Deep Throat, who provided key information and verification to the reporters. Apparently, it was Woodward's suggestion to cast Hal Holbrook in the role. None of the filmmakers knew whether he made this recommendation because Holbrook actually resembled the real man, or to throw speculation into blind alleys. Deep Throat's identity remained one of the best-kept secrets in political history. FBI Associate Director Mark Felt (who did bear a strong resemblance to Holbrook in the '70s) did not reveal himself as this covert whistle-blower until 2005, thirty-one years after Nixon's resignation and eleven years after Nixon's death.

Holbrook's nearly invisible performance and the treatment of the Deep Throat character are two of the keys to the film's success. All the President's Men plays as a film noir mystery, with two detective protagonists venturing out of their depth into the dark and dangerous underbelly of a major city. A memorable actor plays each person they encounter, but, unlike the larger-than-life performances in the best film noirs, these roles are executed with the kind of subtlety and realism required for a film about recent history. Goldman and Pakula actually toned down the hilarious dialogue of Washington Post editor Harry Rosenfeld because they thought the spontaneous humor and cutting remarks the real man was known for played too much like the expertly crafted wit of fictional newsmen. Jack Warden, the personification of a great character actor, plays Rosenfeld and brings with him plenty of cinematic charisma, but never makes us think we're suddenly watching The Front Page. Every small role in the film is impeccably cast because each person the reporters contact is vitally important. Jane Alexander was famously nominated for the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for a performance that consists of barely eight minutes on screen (a record of brevity until Judi Dench won that award in 1998 for playing Queen Elizabeth in Shakespeare in Love for about the same duration).

Even though everyone (then and now) knows how the story ends, All the President's Men is one of the most chillingly suspenseful films ever made. This is due in large part to Goldman's script, Pakula's masterful casting and direction, and Gordon Willis's unparalleled cinematography. Despite the fact that this movie is mostly about two guys making phone calls and standing in dark doorways, All the President's Men is a visually stimulating picture of exceptional merit. Willis's pioneering use of shadow instills a tangible paranoia in the viewer. It is as if we, the voyeurs, are being watched ourselves, along with the characters, by unknown eyes hidden in the darkness. The images of a dark and shadowy Washington, D.C., both in interiors and exteriors, also heighten the film's already grand scale, making the titanic task the two young reporters take on seem all the more insurmountable. The shots inside the Washington Post newsroom set are unrivaled by any film this side of an Orson Wells picture  in their use of dollies, diopters, overhead lighting, and low angles that make giant, open spaces feel claustrophobic. David Fincher and Harris Savides would pay homage to this distinctive visual style in their fact-based film Zodiac (2007)—a brilliant movie whose camerawork, narrative construction, and casting are informed in countless ways by Willis, Goldman, and Pakula's work in this picture.

in their use of dollies, diopters, overhead lighting, and low angles that make giant, open spaces feel claustrophobic. David Fincher and Harris Savides would pay homage to this distinctive visual style in their fact-based film Zodiac (2007)—a brilliant movie whose camerawork, narrative construction, and casting are informed in countless ways by Willis, Goldman, and Pakula's work in this picture.

All the President's Men is one of the most important and lasting American movies of all time, as well as one of the best. I find no aspect of it that could be improved on. It's a compelling mystery, an exciting thriller, a gripping window into the workings of politics and journalism, and a thoroughly entertaining picture with two leads who are both great actors and great movie stars at the height of their careers. It is also one of the key films that demonstrate why the 1970s were such a significant period in film history. Unlike any other period in cinema, the '70s were an era in which challenging dramas trumped escapist fantasies. All the President's Men was the fourth highest grossing movie of 1976, easily topping Richard Donner's acclaimed horror thriller The Omen, Dino De Laurentiis’ big-budget remake of King Kong, and the third Dirty Harry picture The Enforcer. Compare that list to 2007 when the top five box office champs were all sci-fi and fantasy sequels, and Zodiac didn't even crack the top 75. I don't mean to imply that films like All the President's Men can't get made in this day and age, but they are no longer the films that mainstream audiences flock to and embrace. Therefore, they don't inform the public conversation in as profound a way. That ability to reach and affect the broad population is as much a reason why All the President's Men still resonates today, as is its timeless depiction of the search for truth.