The late ‘80s was an era in which movie genres were reinvented by films that followed well-established tropes while simultaneously ratcheting up what audiences loved and expected to see within a given style. These trendsetting pictures added a few key new ingredients to their respective formulas and were so flawlessly executed, and so embraced by the popular culture, that they forever redefined the type of story they epitomized. 1988’s Die Hard did this for the action movie, resetting the bar for every entry in that genre for decades to come. A year later, Disney would revitalize and modernize the fairytale princess genre (and the entire field of animation and film musicals) with the release of The Little Mermaid. Also in 1989, an independent film with the look and feel of a studio picture did the same trick for the romantic comedy. When Harry Met Sally was dismissed by many critics of its day as a mere Woody Allen knock-off, but it was beloved by mainstream culture in a way no Allen film has been before or since. It’s a picture very much of the period in which it was produced, in terms of its fashions, lifestyles, and the way gender is understood, that nevertheless went on to become a timeless classic. It’s an incredibly funny movie that hits on a number of universal themes. But I think what makes When Harry Met Sally so unique in the world of romantic comedies is that its narrative is built on honesty rather than deceit.

The fundamental narrative device of so many cherished rom-coms is a lie perpetuated by one or both of the protagonists that must grow and grow in order to propel the story forward. When this chicanery finally gets exposed at the climax of the third act, the lovers are able to realize what the audience has known all along—that, in most cases, these two people actually do belong together. And when they don’t, then that the feelings these two people believed existed between them were indeed real in spite of the deception they engaged in. From Hollywood’s golden age to the rom-com glut of the late ‘90s, which led to the genre burning out for a time, false pretences have provided the strongest structural foundation for this type of picture.

It’s a tradition that goes back to Shakespeare, who built most of his comedies around characters involved in some form of intentional or unintentional mistaken identity. Romantic classics of literature, ranging from the novels of Jane Austen to plays like Cyrano de Bergerac, trade in impersonation or falsification of certain individuals’ pasts or interests, which, of course, are invariably exposed at the end. Looking strictly at romantic comedy movies of the last hundred years, we can see how critical duplicity is to making them work. Rom-coms can’t exist without an obstacle that keeps the potential lovers apart, and nine times out of ten, some sort of subterfuge is employed to overcome it. The initial tactic usually doesn’t work as intended, which requires a doubling-down that leads to the myriad complications that constitute the second act (often the best part of these movies). By the time the truth finally comes to light, the characters have endured enough together and gotten to know enough genuine aspects of each other to have fallen in love, despite the false foundation on which their relationship was built.

Both Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night (1934), considered the seminal cinematic romantic comedy, and William Wyler’s Roman Holiday (1953), my all-time favorite picture, are about young, rich, prominent women pretending, for various reasons, to be commoners. They meet up with initially cynical newspapermen, hoping to capitalize on their masquerades in order to score a prime scoop. Confidence tricksters from Barbara Stanwyck’s Jean Harrington in The Lady Eve (1941) to Jamie Lee Curtis’s Wanda Gershwitz in A Fish Called Wanda (1988) ultimately abandon or adjust their schemes when they end up falling for their less streetwise marks. Sometimes both protagonists are professional liars, such as the thieves Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins play in Trouble in Paradise (1932) or Julia Roberts and Clive Owen’s corporate spies in Duplicity (2009).

Often it is not the intention of the main character to perpetrate any fraud, but when they are mistaken for someone they’re not, they go along with the misunderstanding, thinking no harm will come of it. Charlie Chaplin isn’t trying to fool the blind girl in City Lights (1931), who assumes he’s a millionaire when he buys her flowers and drives her home with the money and car of a drunken tycoon he’s recently saved from suicide. Similarly, Sandra Bullock in While You Were Sleeping (1995) doesn’t set out to pass herself off as the fiancée of the coma victim she’s secretly been in love with for ages; it just kinda happens.

It’s often clear to the audience from the beginning of the movie how the story will turn out, and the fun comes from watching how clever filmmakers and gifted actors reach these predestined conclusions. In His Girl Friday (1940), a newspaper editor (Cary Grant) convinces his ace reporter and ex-wife (Rosalind Russell) to cover one last big story before she hangs up her typewriter and marries another man. We know it’s merely a ploy to buy Grant time to convince Russell that she should stay with him and the paper, and we know the ploy will work: we just don’t know how. Similarly, in Coming to America (1988), we have no doubt that the wealthy African prince, pretending to be a poor foreign student (Eddie Murphy), will wind up marrying the woman he meets while working an entry-level job at a fast-food restaurant in Queens. But we’re still captivated by all the ways Murphy can play both the prince’s fish-out-of-water naiveté and his inherent sincerity, as he tries to find the kind of true love he doesn’t believe is available to someone whose parents arrange his marriage.

In other prized movie rom-coms, we’re less sure how the picture will wrap up. Jimmy Stewart in The Philadelphia Story (1940) and Julia Roberts in My Best Friend's Wedding (1997) are both overconfident characters who show up to weddings under false pretenses with hidden agendas that don’t work out the way they plan, but they (and we) are left with satisfying resolutions nonetheless. The deceptions on which these plots turn are sometimes born out of pure necessity. The leads in Some Like It Hot (1959) and Tootsie (1982) disguise themselves as characters of the opposite gender for reasons of survival—to escape a hit, in the first case, and out of financial straits in the latter. In those films, falling in love is the charades’ by-product.

In the 1970s, Woody Allen almost single-handedly turned this rom-com formula inside out by making self-delusion the main impediment to lasting romantic happiness. Instead of lying to the people they’re attracted to, the neurotic New Yorkers of Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and most of Allen’s pictures, deceive and undercut themselves by grasping onto intellectual philosophies and moral ideologies that get in the way of establishing solid, stable but flexable relationships. Nora Ephron, the screenwriter of When Harry Met Sally, was fond of saying that she believed there were two schools of romantic comedy: the gentile tradition, in which there is a genuine obstacle keeping the lovers apart, and the Jewish tradition, epitomized by her pal Woody, in which the main obstacle is the internal neurosis of the male character. But this second type of structure can be found in many ’80s and ‘90s rom-coms with distinctly non-Jewish and non-male protagonists. Hugh Grant made a career playing charming but painfully shy guys who can’t bring themselves to confess their love to the women they’re following, and must therefore invent false reasons for their repeated encounters. And Holly Hunter in Broadcast News, Cher in Moonstruck and Dianne Keaton in Baby Boom, all from 1987, are every bit as obsessive or self-protective in their own ways as any of their male counterparts.

Harry and Sally are the same type of voluble, upscale New York professionals found in a Woody Allen movie, but they’re not especially neurotic. Neither are they shy, awkward, or self-delusional. They are somewhat trapped within the narrow constraints of how they each think life is supposed to work, but each is also open to having these views challenged. They don’t deceive themselves in terms of who they are or what they want, and they’re upfront and direct with each other and with their friends about how they experience things. They are, first and foremost, forthright people—occasionally to a fault.

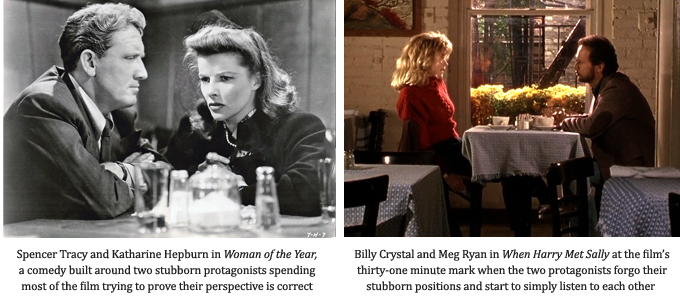

The beginning of When Harry Met Sally sets us up to think we’re going to see a classic "battle of the sexes" story, where the male and female characters are bullheadedly wedded to their differing perspectives and will thus be in opposition to each other for most of the story. This structure is typified by the romantic comedies of Katherine Hepburn and Spenser Tracy, whose spend the bulk of the narrative time in the eight films they made together arguing and working to prove to the other that their perspective is the correct one. Only at the end is a rapprochement reached.

When Harry Met Sally’s unique structure gives us all that comedic stubbornness and bravado, but condenses it into the lengthy first act. When we first meet the two characters they are college students in their early twenties, full of themselves and overconfident in their views on life. Harry is an arrogant, but funny cad, and Sally is a prissy, but charming, fussbudget. The film then jumps forward five years, when they run into each other again, this time on a plane. Harry is about to get married and is a little less aggressive with his philosophy, but he’s still that same pompous blowhard. Sally has just started dating a handsome guy named Joe, whom Harry used to know, and she’s a little more open-minded about other people’s perspectives on life. But in their late twenties, these two both are still fully enmeshed within the confines of the ridged identities they’ve carved out for themselves.

The film then skips ahead five more years to when Harry and Sally cross paths again, this time in a bookstore. By this point they’ve both been humbled by the break-ups of their first major adult relationships. They make small talk, and there’s a moment when they could each make the choice to conceal the truth of how they are really doing and make this third encounter the shortest and final one of their relationship. But each of them at this moment chooses to dispense with all pretence and answer the other’s questions honestly.

At the thirty-one-minute mark, after Harry and Sally have disclosed their recent break-ups and expressed genuine compassion for each other’s situation, Harry asks Sally, “So what happened with you guys?” The film cuts to the two of them sitting in a restaurant, with Sally telling the honest story of the relationship impasse she reached with Joe. I consider this elliptical “time cut” to be as fascinating, and as important to its genre, as the lauded cut in 2001, A Space Odyssey, when director Stanly Kubrick jumps from the prehistoric era to the space-age future, via a match-cut from the bone weapon, tossed into the air by the dominant ape, to the American nuclear satellite floating in orbit around the Earth.

The 2001 cut skips past the evolution of all humanity over millions of years in a split second and invites us to contemplate what the significance of all that progress was. The cut in When Harry Met Sally simply glosses over whatever logistical conversation the two protagonists had about where they might go grab lunch and continue their deeper discussion, but it is at this moment that this romantic comedy differentiates itself from most every other example of the genre. Harry and Sally let down their guard here at the transition into the second act. They forgo reverting to any lies or half-truths, and they stop trying to convince the other that their worldview is correct. Of course, these two are still clinging to their ingrained philosophies, but they have reached a point where they’re open to having those beliefs challenged and altered as a result of listening and sharing with the other person.

The frank, candid discussions that make up the bulk of When Harry Met Sally are why I believe a movie that, upon release, appeared utterly familiar to audiences in terms of situations, settings, character tropes, and set pieces, also felt so fresh and even revolutionary. But honesty was never an organizing principle that the creators of this movie set out to explore. Nor is it the film’s central premise, or something critics ever singled out about it. The principal question When Harry Met Sally asks is: Can men and women be friends without sex getting in the way? That’s a pithy, poster-tagline way of saying that the movie interrogates differences between genders in a light, playful, humorous way that also drills down to the root of some fundamental truths about navigating binary gender differences.

When Harry Met Sally was born out of director Rob Reiner’s divorce from actress and director Penny Marshall. Reiner was depressed, angry, and pessimistic about love and relationships, but his desire for sex kept him in the dating game. His romantic experiences as a divorced single man did not make him happy, and they weren’t too great for any of the women he dated either. In the early 1980s, Reiner and his producing partner Andrew Scheinman approached the erudite New York columnist, author, and screenwriter Nora Ephron about a project they hoped she might write for them. Reiner had recently seen Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage (1973) and had hit upon the idea of doing something along the lines of "Scenes from a Friendship," featuring men and women arguing about their various differences. Ephron was not interested in this pitch, but she did enjoy having a long lunch with Reiner and Scheinman at the Russian Tea Room. Always a journalist and deeply curious person, she asked them questions about their lives and was both fascinated and horrified at the stories they told her about being straight, privileged single men living in the pre-AIDS ‘80s: fascinated, because their stories were so eye-opening and self-deprecatingly funny, and, horrified because both men seemed so misogynistic, deceitful, and clueless about what women really think and feel.

Years later, Ephron and Reiner met again in New York. He was still trying to come up with a movie premise that could contain all the funny and painful situations he’d found himself in over the previous ten years of dating. He pitched several of these concepts to Ephron, but he didn’t get a nibble until he presented the last of his premises: a man and a woman become friends right after going through the breakups of their first major adult relationships; they decide not to have sex with each other out of the fear it will ruin their friendship, and then they do have sex with each other, and it ruins the friendship. Ephron loved that concept. The film’s three acts were easy to see, and there appeared to be plenty of room to create funny, yet absorbing, resonant situations within it. She signed on to write the screenplay and Reiner went off to make his third feature, the successful coming-of-age period drama Stand By Me (1986).

Ephron had learned her screenwriting craft working for Mike Nichols (for whom she co-wrote Silkwood in 1983 and adapted her own novel Heartburn in 1986), and she was certainly influenced by the comedies of her friend Woody Allen. But when she wrote this original screenplay, then referred to as Boy Meets Girl, she had old-fashioned Hollywood rom-coms in mind. She made her two protagonists opposite types who dislike each other at first but who can’t help falling for each other. Harry Burns is a depressed but funny pessimist, enamored of his own dark side, outspoken and chaotic, which was how Ephron viewed Reiner. She based Sally Albright on herself: an optimist, more mature and socially refined than Harry, but overly structured and rigid in her opinions and attitudes.

In a picture from Hollywood’s Golden Age, characters like these might be forced into cohabitation due to some external circumstance, like being stuck traveling together as in Capra’s It Happened One Night (1934) or Reiner’s own The Sure Thing (1985). But in this script, the man and woman aren’t compelled by circumstance to coexist; they choose to spend time together because they enjoy each other’s company. Ephron was confident that her characters’ opposing viewpoints on life could provide plenty of comedic and narrative tension without some external obstacle and without extraneous subplots about their working lives or families of origin. As in some of Hollywood classics she loved, Ephron also created a best friend for each protagonist. For Sally, she wrote a wisecracking, less-lucky-in-love, Eve-Arden-type gal-pal, ultimately played by Carrie Fisher, into whom she poured all the aspects of herself that she wasn’t drawing on for Sally. And she gave Harry a buddy much like Andrew Scheinman was for Reiner, with Bruno Kirby eventually cast in the role.

Reiner and Ephron met up after another year and talked more about the script. Ephron went off to write another draft while Reiner made the fractured fairytale The Princess Bride (1987). Disappointed with how 20th Century Fox had bungled the lackluster release of Princess Bride, Reiner and Scheinman set up their own production company, Castle Rock Entertainment, with some executives from Fox and Nelson Entertainment. Nelson owned the home video rights to Reiner's early hits This Is Spinal Tap, The Sure Thing, and The Princess Bride. Correctly betting that these ancillary rights would be lucrative, Reiner and Scheinman planned to self-finance their next project, which they hoped would be Ephron’s script. They all got to work polishing the existing draft.

Ephron had written a lean, sharp, and sophisticated screenplay with a hefty number of jokes that felt organic to the characters. She had devised a lengthy first act in which her two protagonists meet twice over the span of five years, and we get to know them well before the story proper gets started. It was an unusual way to begin a film. Reiner contributed a key structural device that was also original, if potentially awkward: cutting interstitially to testimonials from random married couples sitting on a sofa telling the stories of how they met and fell in love. This device was inspired by a dinner Reiner had at the home of a friend and the friend’s parents. Hoping to engage the subdued, elderly father at the head of the table, Reiner asked how he and his wife had met, at which point the man sprang to life and told the charming story  that became the opening lines of When Harry Met Sally. Cutting away from the main narrative to these unrelated anecdotes made the first act even longer and more staccato, but everything in it seemed so funny that Ephron and Reiner trusted it would work. Reiner shot actual elderly couples telling their real-life stories in the hope they could be used in the film, though ultimately Ephron condensed these interviews into pithy monologues or exchanges to be reenacted by professional actors.

that became the opening lines of When Harry Met Sally. Cutting away from the main narrative to these unrelated anecdotes made the first act even longer and more staccato, but everything in it seemed so funny that Ephron and Reiner trusted it would work. Reiner shot actual elderly couples telling their real-life stories in the hope they could be used in the film, though ultimately Ephron condensed these interviews into pithy monologues or exchanges to be reenacted by professional actors.

For Harry, Reiner was keen on casting his best friend Billy Crystal. The two had met when Crystal was hired to play his fictional best friend on an episode of All in the Family, the iconic Norman Lear sitcom in which Reiner became a star. Crystal, a successful stand-up comic who had become famous on the sitcom Soap and as a cast member and frequent host of Saturday Night Live, was not yet a movie star. Aside from cameo roles in two of Reiner’s earlier pictures, Crystal had appeared in only a handful of films, mostly the directorial débuts of other actor/comedian friends: Joan Rivers' Rabbit Test (1978), Danny DeVito’s Throw Momma from the Train (1987), Henry Winkler’s Memories of Me (1988), and opposite Gregory Hines in Peter Hyams’s buddy cop picture Running Scared (1986). Crystal wasn’t exactly a box office star, but he was a well-known celebrity. Reiner tested a few more famous actors, like Albert Brooks, but since his own company was financing the movie, there was no studio telling him not to cast his best friend as a lead. Ephron had already incorporated elements of the two men’s relationship into her script, including, notably, the scene in which Harry calls Sally to complain about how depressed he is, and they watch Casablanca on TV together from their respective apartments. After Reiner’s divorce, he and Crystal would talk every night on the phone while watching the same old movie on television, and much of their actual conversations ended up in Harry and Sally’s dialogue.

To play opposite Crystal, Reiner and veteran casting directors Janet Hirshenson and Jane Jenkins chose Meg Ryan, an up-and-coming TV actress just starting to make a name for herself with girl-next-door roles in popular features like Top Gun (1986) and Innerspace (1987). Her chemistry with Crystal was enchanting. The two actors light up the screen in this film, which solidified them both as major stars for decades. As much as Ephon’s whip-smart script and Reiner’s elegant direction, it’s these two leads’ connection with each other and the audience that made the film the hit it became.

Before shooting, Reiner scheduled two weeks of rehearsals with Crystal, Ryan, Carrie Fisher, and Bruno Kirby. Ephron attended all these sessions and tailored her script to the four leads’ personalities, adding in all the ideas and improvisations that arose—especially those from the fertile comedy minds of Crystal and Fisher. Crystal contributed far more than just a few good jokes and funny voices. Many of his ideas were for situational gags that enhanced Ephron’s well-crafted scenes, such as spitting grape seeds out the car window when Harry and Sally meet, staging his first scene with Kirby at Giant Stadium where their serious conversation about divorce is repeatedly interrupted by their need to participate in “the Wave” with the rest of the crowd, and Harry bumping into his ex-wife at the Sharper Image while performing a goofy karaoke with Sally.

Ephron, Reiner, and Scheinman continued to hold script meetings in diners and delis where they would share their differing perspectives on life, love, dating, and friendship. Reiner was fascinated by how Ephron, a true foodie, would never order anything directly off the menu, and constantly told the wait staff or chef how to prepare her meal or beverage. It never occurred to Ephron that there was anything odd about ordering food the way she wanted it, but she enjoyed how tickled Reiner was by this behavior. He wanted this quirk incorporated into Sally’s character, and it went into the script. Ephron continued to grill the two men, who were still bachelors, about dating, observing that, from their behavior towards the women they slept with, it sometimes sounded like they were out for revenge against her entire gender. That went into the script too.

At one lunch, Ephron was interested to hear Reiner and Scheinman confess that all men want to go home as soon as sex is over. They described the stories they would make up about why they needed to run out the door, fabrications they assumed would never be discovered since the sexual encounters were most often one-night stands. When Reiner asked Ephron to reciprocate by telling him and Scheinman something they didn’t know about women, she confided that most women fake orgasms. Reiner and Scheinman didn’t believe most women did such a thing, and certainly that no one had ever faked orgasm with either of them. Ephron assured them that she had no doubt many women they had been with had faked it. Reiner proceeded to ask every woman in his office if they’d ever faked orgasm (a workplace move he’d surely think more carefully about today), and was astonished that well over 60% said yes—not to mention the many women who, he assumed, might not be telling him the truth about faking.

This revelation knocked Reiner on his heels and led to the creation of the film’s most iconic scene, in which Sally, lunching with Harry in Katz's Delicatessen, loudly and dramatically demonstrates how easy it is for a woman to fake an orgasm. In a perfect example of the groove that had developed between the film’s key creatives, Ephron worked the fake-orgasm discussion into an existing scene in the script. Ryan hit upon the brilliant idea of performing a full-on fake orgasm in a public place like a restaurant. Crystal then contributed the line that capped the scene and became the film’s biggest laugh, delivered by a woman at an adjacent table, who tells the waiter, “I’ll have what she’s having.” And Reiner hit upon of the perfect person to deliver that line: his mother Estelle. The collaborators’ creative energy was sizzling.

The late addition of the Katz’s Deli orgasm scene was indicative of how this production felt to all involved, like the gods of film had blessed it. This was one of those rare movies in which everything came together with ease, and a joyous, stress-free shoot resulted in a delightful, easygoing picture. Crystal is fond of telling a story about the last day of filming in Central Park, which included photographing the signature shot of Harry and Sally walking in front of lush, multicolored fall leaves. The instant the cameras captured the best take of the scene, rain started to pour, and all the leaves promptly fell off the trees. It was as if Mother Nature was holding back, waiting for the production to get the image that would, in many markets, become the film’s poster.

Still, filmmakers never know if what seems to work well when shooting will actually connect to an audience. In an interview not long before her death, Ephron recalled being on set for the scene in which Harry and Sally set each other up with their best friends. As she watched Crystal, Ryan, Fisher, and Kirby take her dialogue and make it sing, it made her feel like the movie would be a smash. Then, just a few hours later, she went to view dailies with Reiner and saw footage of the film’s final scene, shot just the day before. That experience convinced her that the movie would bomb.

The ending of When Harry Met Sally was reshot twice. Reiner and Ephron, who had both been through nasty divorces, didn’t originally plan on having their two friends-turned-lovers end up together at the end of the film. But as production neared, it became clear that the script they had created should end with Harry and Sally living happily ever after, like one of the married couples that appear in the interstitial testimonials, instead of parting as friends. After all, while the film concerns real emotions and relatable situations, and although it’s shot in authentic locations in the actual city where the story takes place, the movie's reality is heightened. This New York is breathtakingly beautiful at all times, during every season, and thirty-two-year-old protagonists can afford fabulous apartments and enjoy days free from stress, work deadlines, and apparently any other commitments.

Like previous hit romcoms of the ‘80s, such as Splash, Moonstruck, and Working Girl, there is a major element of wish fulfillment to this picture, and a happy ending feels right, if maybe less realistic. But when the ending was first shot, it came off as saccharine. A second attempt failed too. The finished film’s final monologue, in which Harry explains how he came to realize that he wants to spend the rest of his life with Sally, was, by all accounts, another collaboration between the creative foursome, with Crystal contributing many of the key lines. Reiner and Ephron felt it was finally specific and personal enough that they could believe in it and be moved by it. Go-for-broke, declarative “I love you” speeches had ended romcoms before, but this one became perhaps the genre’s most shamelessly emulated convention in the wake of When Harry Met Sally’s success. Yet even three decades and countless lesser versions of this speech later, Crystal’s words and delivery still work for all but the most cynical viewers.

It helped that, by the time the ending was shot for the third time, Reiner had met the woman who became his second wife, and he was feeling more optimistic that romantic relationships could indeed last. They’d even met during the production of When Harry Met Sally, in another one of those magical moments that seemed to permeate the making of this picture. One day Reiner was complaining to the crew about his life, as he was wont to do, and he looked over at a magazine that had actress Michelle Pfeiffer on the cover, along with a story about her recent divorce. Reiner remarked to cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld that Pfeiffer seemed nice, and maybe he should call her, to which Sonnenfeld replied, “You’re not gonna call her; you’re gonna call my friend Michele Singer. She’s who you’re gonna marry.” Sonnenfeld invited Singer to a lunch a week later, where she and Reiner met. They went out to dinner, fell in love, got married a few months later, and are still married today. It might not quite be a “how-we-met” story worthy of When Harry Met Sally’s testimonial couples, but it’s still a charming and fitting anecdote. And it’s yet another indication of the storybook quality that seemed to surround When Harry Met Sally and help it feel so truthful, despite its romanticized gloss.

Still, some critics fault the movie for being one of the far too many pictures that spread Hollywood’s unrealistic happily-ever-after narrative. Here again, however, is where I think this film improves upon rom-com tropes, rather than falls victim to them. After all, what exactly is the false fantasy perpetuated by When Harry Met Sally? Is it inaccurate that men and women can work on trying to better understand each other to the point where a long-lasting happy relationship is possible? Of course not; there are many happy couples out there. And this is not one of those films that try to convince you that it’s possible to have it all, or that to find love, you have to wait for the right person to come along, or change yourself into something you’re not. This movie simply asserts that friendship is as important to a successful relationship as sexual attraction, and that it’s possible to be yourself and still find someone who’ll love you, as long as you’re willing to consider that your way of looking at life might not be 100% correct. It might require the kind of refinement that comes through the work of being in a long-term romantic partnership.

Critics of the time also complained that When Harry Met Sally was unoriginal. This charge grew primarily from the fact that Woody Allen had already made romantic comedies set in New York, so, I guess, there wasn’t a clear need for this one. And many claimed it was as phony as a sitcom, singling out the orgasm scene as something that would never happen in real life. But that scene is exactly the kind of classic movie moment that lasts in our collective imagination specifically because, though it wouldn’t actually occur in life, it feels credible in an artfully, comically heightened reality. More importantly, the truth being explored in this scene isn’t that straight-laced people like Sally simulate sexual climax in public while eating a sandwich; it’s that most women have faked orgasms, and that most men can’t tell the difference.

It may be difficult for those who grew up in a post-When Harry Met Sally, post-Seinfeld, post-Sex in The City, post-Internet world to u nderstand what a revelatory scene this was for audiences in the late ‘80s. Even urban sophisticates like those who made this film didn’t often discuss such matters in mixed company at that time. The scene encapsulates the movie's core theme: that men and women view sex and relationships in fundamentally different ways. Some could claim that the scene relies on a now-outdated, binary way of looking at gender dynamics, but when this scene came onscreen in 1989, audiences around the world exploded with the specific laughter of recognition. Women couldn’t believe a mainstream movie was outing this secret, and men didn’t want to believe it was true. But if those same men weren’t convinced by Sally’s line—“It's just that all men are sure it never happened to them, and most women at one time or another have done it, so you do the math”—her counterfeit climax sold it. And of course, Estelle Reiner’s scene-topping, “I’ll have what she’s having,” deadpan got such a laugh in the theaters that it obscured the entire following Ray Charles song that underscores the montage of fall changing into winter.

Earlier movies about the male/female divide were played on either a far broader or far more cerebral level, and the perspective of such films almost always slanted too heavily towards one side or the other. But When Harry Met Sally covered ground that most men and women could relate to equally. The film’s unforced, evenhanded approach to male and female attitudes and viewpoints is one of the keys to its success and longevity. Ephron and Reiner, Crystal and Ryan, Fisher and Kirby all embrace the strengths and flaws of their respective genders in ways that feel comical, affirming, and, most of all, accurate.

Ephron’s self-aware wit infuses the movie with a sharp and bright female point of view that the vast majority of films directed by men lack. But she’s such an astute observer of human behavior that her male characters are just as well realized. And, of course, Reiner, Scheinman, and Crystal brought much of their own personalities and experiences to Harry, while Ryan imbued Sally with her own distinctive charm. As I noted earlier, Crystal contributed tremendously to the final shooting script. I’ve seen this picture well over fifty times, and I count an astounding 115 places when I’ve laughed out loud during one viewing or another. From what I can guess after studying all the various accounts of the screenplay’s development, at least twenty of those laughs came directly from Crystal, as did key elements of Harry’s final speech, and as I noted, it was Ryan who contributed the idea for the film’s most memorable scene.

But fans, reviewers, and even critics (who should know better) always ascribe more importance to contributions made by actors than is pertinent. Film legends, DVD commentaries, Q&As, and behind-the-scenes featurettes are so full of anecdotes about improvisation that we tend to think dialogue is the most important aspect of a screenplay. After all, creating what characters say is all that many audience members can conceive of when they imagine a screenwriter’s job. But there’s a reason the Writers Guild considers dialogue the least important aspect of the screenwriter’s craft when it comes to arbitrating credits. Dialogue can be (and often is) made up on the spot, whereas structure, theme, character, and all the critical elements of cinematic storytelling cannot be spontaneously created. The notion of spontaneously willing an entire film into existence on the fly is especially ridiculous when working in a form as delicate as the rom-com, but even “totally improvised movies,” like Reiner’s satirical This is Spinal Tap and the films of Christopher Guest that followed it, are not fully improvised from scratch: only the dialogue is. I point this out not to belittle the talent and contributions of actors who are brilliant improvisers but rather to contextualize the importance of that skill in creating a successful movie. This picture achieves greatness because of the unique combination of the many talents that converged to make it, but it was unambiguously Ephron’s rock-solid screenplay that provided the foundation upon which everything stands.

When Harry Met Sally is not popular with most critics who subscribe to the auteur theory, for the obvious reason that this film so clearly did not spring fully formed from the mind of one artistic genius. But for movie-lovers like me, who believe the greatest pictures result from an un-engineerable combination of talents and the fortuitous timing of disparate elements—many of which are beyond the filmmakers’ control or even awareness at the time of production—this feature is a shining example of what can happen when all the cinematic stars align and everything magically falls into place to create a film that can stand for the ages.

For evidence of how rare a movie like When Harry Met Sally is, one need look no further than scripts Crystal has written (Memories of Me, Mr. Saturday Night, My Giant, America's Sweethearts) or films Ephron has directed (This Is My Life, Michael, Mixed Nuts, Lucky Numbers). Few would argue the merits of these lackluster pictures. Indeed, each member of When Harry Met Sally’s key creative team endeavored to recapture the magic of the film and failed. Reiner tried with The Story of Us (1999), which isn’t a rom-com but still co-opts characters, tropes, and entire scenes from When Harry Met Sally—including an egregious example of an overwritten, go-for-broke “I love you” ending speech. Ephron re-attempted Harry and Sally twice, with Sleepless in Seattle (1993) and You've Got Mail (1998), both of which paired Ryan with Tom Hanks and, despite the onscreen chemistry, resulted in tedious pictures. Ryan herself had the most success returning to the Harry and Sally well with the strained but watchable French Kiss (1995), which she co-produced with director Lawrence Kasdan and in which she played a Sally near-clone. At the bottom of this cinematic recycling bin is Crystal’s Forget Paris (1995), a dead-on-arrival romantic comedy that he produced, co-wrote, and starred in with Debra Winger. These labored features are full of embarrassing casting choices, artificial character traits, shameless pandering to the audience, and scenes that feel like they came from a rom-com handbook rather than out of lived human experience.

Aside from those declarative monologues that conclude so many romantic comedies of the 1990s, the revitalized trope When Harry Met Sally popularized that became the most hackneyed the fastest was the idea that each protagonist should have a best friend to confide in. This device instantly became a lazy way for writers, directors, and actors to convey exposition, state subtext, and wink at the audience. Sleepless in Seattle is the worst offender here, with Reiner himself playing Tom Hank’s buddy in a hammy performance, and Rosie O'Donnell, as Ryan’s gal pal, practically glaring into the camera and shouting the theme of the movie to the audience at multiple occasions. So many of the surface details of When Harry Met Sally were reproduced in inferior films, but the things that made it such a unique example of the rom-com genre—dispensing with an external or internal obstacle to prevent the lovers from getting together, and forgoing any need for them to deceive each other—has rarely been repeated.

Those are the aspects that I believe make the film distinctive. The astutely observed writing and universally relatable themes are what make it timeless. But what makes viewers return to When Harry Met Sally over and over is simply how much we want to submerge ourselves in the world of this picture. There are few Hollywood movie characters I’d rather spend time with than Crystal’s Harry and Ryan’s Sally. And, though I moved to New York only a few months after first seeing this film and discovered the city I was living in bore little resemblance to the movie’s beguiling, spacious, autumnally-colored wonderland, the Manhattan of When Harry Met Sally is the city most of us want to believe New York is really like.

The soundtrack of standards from the American songbook, performed by the then-obscure, twenty-year-old piano-playing crooner Harry Connick Jr., envelops the film in nostalgic feelings, even if we have no previous association with any of those songs. Using new recordings of old standards was another way Reiner modernized a pre-existing trope of the genre and made it more universal and timeless. Woody Allen scored all of his movies with jazz standards, but he always chose vintage recordings that harkened back to an earlier time. While Connick’s singing style owed a great deal to Frank Sinatra, he possessed a distinctly modern way of putting an old song across. Outside of Allen’s work, most rom-coms of the ‘80s were scored with contemporary pop songs that ground them squarely in the era in which they were made. But the perennial tunes recorded for this soundtrack by Connick and by the gifted composer, lyricist, and musical encyclopedia Marc Shaiman contribute mightily to When Harry Met Sally’s timeless quality.

The last and perhaps most critical reason this film is so endlessly re-watchable is how lean and compact it is. It was not long after this picture that mainstream movies began to expand in length as if a film’s run time was in direct proportion to its quality and importance. Superstar Kevin Costner surely had something to do with this trend, producing several lengthy features in the ‘90s, including romantic pictures like The Bodyguard that clocked in at well over two hours. And Judd Apatow normalized the indulgent, overcrowded comedy in the Aughts with offerings like Knocked Up, Funny People, and This Is 40. Whereas When Harry Met Sally is part of a tradition that dates back to the early sound era, which maintained that comedies should not run much longer than ninety minutes. This efficiency leaves the viewer wanting more, and thus audiences return to the movie again and again the way we keep returning to the classic romcoms of the 1930s and ‘40s.

Studying When Harry Met Sally’s structure is fascinating in terms of where the movie is allowed to breathe and take its time without ever feeling slow or meandering and where it speeds up without seeming rushed. When running a 35mm print of this five-reeler, it’s surprising to note that the opening chapters, which show the first two times Harry and Sally meet, at five-year intervals, lasts far longer than a single reel—this first act is a full third of the picture. And the point at which the two friends finally do give in and make love comes right at the end of reel four, leaving less than half an hour for the complications of that choice, and the film’s resolution, to play out.

If I’ve had any complaint about When Harry Met Sally, it’s that I’ve wished Sally was given one more scene to help us empathize with how angry and cold she is to Harry in the weeks after they have sex. It is perhaps a missed opportunity for a film that hinges on this act to further explore how awkward their friendship becomes once they’ve crossed that line. The movie provides ample reasons why Sally would become distrustful and resentful of Harry after they make love, knowing all too well his views on romance and the history of how he treats the women he’s slept with. But I’ll always wonder what one additional brief scene in that last reel might have accomplished.

When Harry Met Sally catapulted each member of its creative team to a new level of success, though nothing any of them ever did after 1989 came close to achieving the perfection of this movie. Billy Crystal appeared in many hit comedies, including City Slickers (1991), Analyze This (1999), and the Disney/Pixar series Monsters, Inc. (beginning in 2001), but aside from these films and his early work as a sketch comedian, he’ll perhaps be best remembered in Hollywood as the greatest-ever host of the Academy Awards. There he remains the only master of ceremonies for that high-stakes gig to have been a well-established member of the film industry, and a lifelong fan of cinema with a deep knowledge of its history, and a first-rate stand-up comedian equally at home with pre-scripted material and spontaneous banter. Meg Ryan went on to a decade-long stint as America’s sweetheart in movies like Sleepless in Seattle (1993), You've Got Mail (1998), and Kate & Leopold (2001), but she had a rough transition into dramatic roles with pictures like Courage Under Fire (1996), Proof of Life (2000), and In the Cut (2003).

Reiner won wide acclaim and many award nominations for films like Misery (1990), A Few Good Men (1992), and The American President (1995), but none of the fifteen features he directed after When Harry Met Sally achieved the level of excellence of his first five movies (all made between 1984 and 1989!). Ephron continued writing brilliant, urbane, humorous essays, a craft at which she had few peers, culminating in two outstanding collections: I Feel Bad about My Neck: And Other Thoughts on Being a Woman (2006) and I Remember Nothing: And Other Reflections (2010). And after an uneven secondary career as a film writer/director and a playwright, she finally directed one excellent movie, Julie & Julia (2009), which combined her three great passions: writing, cooking, and analyzing the idiosyncratic aspects of all forms of relationships.

The fact that mainstream romantic comedies as satisfying as When Harry Met Sally don’t come across our movie screens more often isn’t surprising. It is perhaps the most difficult genre to get right, make fresh, and feel truthful. The dream team that created this picture all came together at the perfect points in their respective creative development to concoct a charming fiction born out of honest communication, observation, and curiosity.