Among the hundreds of film series in the history of Western cinema, the James Bond movies tower over all rivals when it comes to cultural influence, financial success, and enduring popularity. Over a quarter of the world’s population has seen at least one of Secret Agent 007’s cinematic adventures. Based on Ian Fleming's widely-read spy novels, the official series has run for more than fifty years, across twenty-three pictures and six leading actors. Each new entry has attempted to simultaneously outdo its predecessors while maintaining tradition and continuity. Changes buffet the real world, but decade after decade the Bond series has remained fashionable, despite the fact that its subject, style, and attitudes are firmly rooted in a now long-gone time and place—Great Britain during the Cold War.

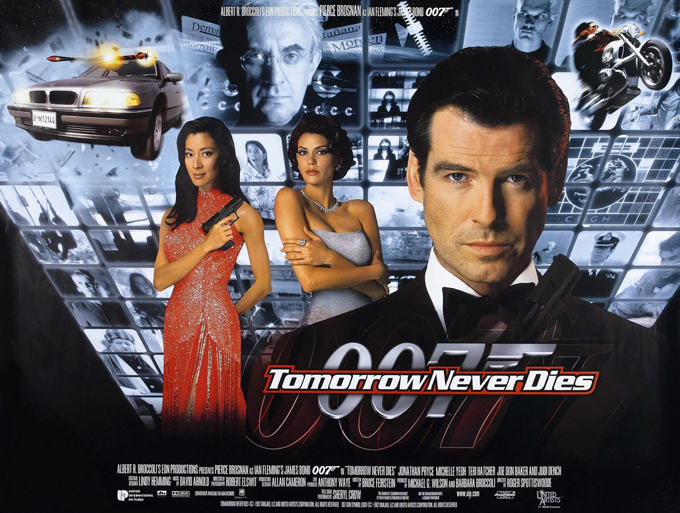

I saw my first Bond movie in 1981, when I was ten years old. It was For Your Eyes Only, and it was a good place to start, as it remains one of the better films of the series. I was hooked from the first frame of the pre-credit sequence, and I've never missed a Bond picture since. Even during the tedious Pierce Brosnan years, I still showed up at the first screening on opening day whenever possible. Of course, my double-0-philia is directly connected to my passion for movies in general. The first video rental store in my town was a Rent-A-Center that offered washer/dryers, vacuum cleaners, TVs, VCRs, and a "massive selection” of about 235 VHS cassettes, including all the Bond movies. Before our town got a proper video store, I rented every tape on that shelf about twenty times. I devoured the 007 films in short order, internalizing their dialogue, editorial rhythms, and visual style, and promptly moved on to Fleming's novels and short stories, and then behind-the-scenes magazine pieces, books, TV specials, and all manner of Bond production histories, anecdotes, and tall tales about the casts and crews.

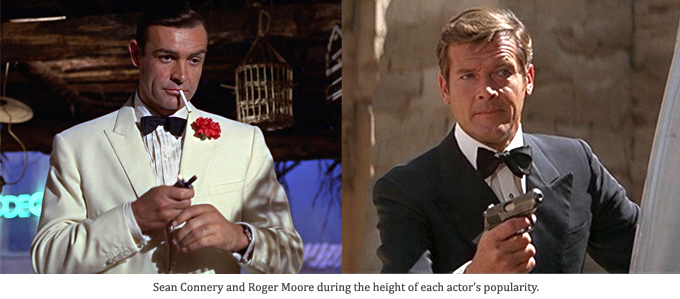

Like most Bond fans, I was partial to the first actor I saw play 007, which in my case was Roger Moore. To a young and uninitiated 1980s kid like me, Moore seemed like the real James Bond, the one in the newer, cooler films. But like practically everyone else, I soon came to view Sean Connery as the true James Bond. The Connery movies looked old and dated on my badly transferred, overplayed VHS cassettes, but once the Criterion Collection released the original pictures on laserdisc, and, later, when MGM released them on DVD and Blu-ray, anyone could see that the early Bond films were the quintessential Bond films. Not only was Connery’s characterization superbly entertaining, but the original power and allure of the James Bond mystique, style, and tone were an indisputable part of the 1960s British invasion, and the pictures of that era are simply more resonant and iconic. For the most part, they are also closer in spirit to the original novels.

Fleming’s Bond tales, which comprise eleven novels and two short story collections, are better reads than they are usually given credit for. While he never rises to the level of Graham Greene, Raymond Chandler, or Patricia Highsmith, Fleming is certainly the equal of authors like Mickey Spillane, Dorothy Sayers, and even Dashiell Hammett. Fleming’s strongest suit is his descriptive prose. Reading passages about Jamaica, his adoptive home and the setting for many of his books, you feel as if you could visit the island and know your way around (if you went back in time). But he is equally gifted at describing places he never actually saw, like Istanbul. In fact, Fleming convincingly invents much about the countries that James Bond visits purely out of his imagination—like the non-existent feudal castles of Japan in You Only Live Twice.

Fleming’s books bear out his reputation as a chauvinist with colonialist attitudes about white, English, male superiority. Yet while these inescapably unenlightened attitudes underlie most of his novels, he nonetheless dreams up a fair-sized array of heroic, multilayered characters, several of whom are women and people of color. Many of the stories feature vibrant, capable, and deeply sympathetic female characters like Honey Rider in Dr. No, Judy Havelock in For Your Eyes Only, and Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo in On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Perhaps these physically and intellectually stimulating members of the opposite sex represent a type of woman Fleming longed to meet but never actually did, immersed as he was in an intentionally isolated lifestyle. Though admittedly not an exact analogy, the smart, sexy, adventurous women Fleming envisioned can be seen as bearing some relation to the rich, sensitive, honorable male suitors Jane Austen fashioned in her novels; both writers, though on different literary levels, created idealized members of the opposite sex who were perhaps not as plentiful in the daily reality of their lives.

Fleming’s books bear out his reputation as a chauvinist with colonialist attitudes about white, English, male superiority. Yet while these inescapably unenlightened attitudes underlie most of his novels, he nonetheless dreams up a fair-sized array of heroic, multilayered characters, several of whom are women and people of color. Many of the stories feature vibrant, capable, and deeply sympathetic female characters like Honey Rider in Dr. No, Judy Havelock in For Your Eyes Only, and Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo in On Her Majesty's Secret Service. Perhaps these physically and intellectually stimulating members of the opposite sex represent a type of woman Fleming longed to meet but never actually did, immersed as he was in an intentionally isolated lifestyle. Though admittedly not an exact analogy, the smart, sexy, adventurous women Fleming envisioned can be seen as bearing some relation to the rich, sensitive, honorable male suitors Jane Austen fashioned in her novels; both writers, though on different literary levels, created idealized members of the opposite sex who were perhaps not as plentiful in the daily reality of their lives.

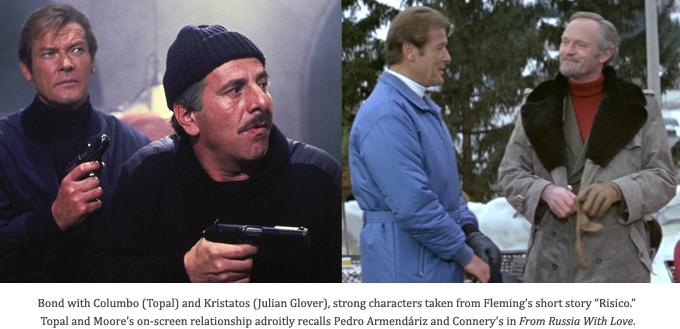

A critical theme of comradeship runs through all the books. James Bond’s respect for, and loyalty to, the allies and colleagues he teams up with in each adventure is formed by their shared experience, not their nationality. The Turkish station chief Darko Kerim in From Russia, with Love, the redoubtable Cayman Islander Quarrel in Live and Let Die and Dr. No, the Japanese agents Tiger Tanaka and Kissy Suzuki in You Only Live Twice, and the American CIA operative Felix Leiter in several books, are all savvy and courageous individuals in whose hands Bond places his life on many occasions. If harm comes to these friends it causes him deep pain and often instigates ill-advised ideas of revenge. While clearly part of a longstanding convention of male bonding in high-risk situations, such as appears in Moby Dick's Ishmael and Queequeg, Bond’s allegiance to those he works with as well as to the innocents who are often enlisted in his missions is a major part of what endears us to him.

Of course the Russians and members of other communist nations are always antagonists in the 007 novels, but Fleming paints them as skillful and worthy adversaries. The foreign agents Bond goes up against are sharp, deadly foes, often with complex views about their government that mirror Bond’s about his own. Interestingly, Bond (and Fleming) often seems more contemptuous of America than any other nation. Though the United States was England’s greatest ally during the Cold War, the books display a decidedly condescending attitude towards the superpower that was rapidly eclipsing Great Britain.

While Fleming did serve in Britain's Naval Intelligence Division during WWII, and though he based many of Bond’s specific tastes and attributes on himself, his novels were not autobiographical. The author always claimed that his original intention was to write stories about a relatively dull man to whom interesting and exciting things happened. He even lifted the character's name from the author of his favorite book of ornithology, Birds of the West Indies, because it sounded so bland and forgettable. But the novels evolved as they progressed, and Bond's character did too.

Fleming’s books typically begin with absorbing introductory chapters, in which 007 becomes involved in a mission that seems more casually curious to him than of dire import to his country. Frequently, he tangles with the principal villain early on, often over some sort of game. These passages are reliably good reads, but the narratives tend to falter by their big action climaxes, which often grow tiresome rather than exhilarating. The third novel, Moonraker, best illustrates this downward progression. In Moonraker, 007 is assigned to determine how a wealthy industrialist named Sir Hugo Drax is cheating at bridge. The first half of the book is devoted to Bond getting into the card game, sizing up his opponent, and outplaying him. The pleasure in these pages is unwavering. But the second half, in which Bond tries to stop Drax from destroying London with a nuclear-armed rocket, is pretty silly.

Fleming’s books typically begin with absorbing introductory chapters, in which 007 becomes involved in a mission that seems more casually curious to him than of dire import to his country. Frequently, he tangles with the principal villain early on, often over some sort of game. These passages are reliably good reads, but the narratives tend to falter by their big action climaxes, which often grow tiresome rather than exhilarating. The third novel, Moonraker, best illustrates this downward progression. In Moonraker, 007 is assigned to determine how a wealthy industrialist named Sir Hugo Drax is cheating at bridge. The first half of the book is devoted to Bond getting into the card game, sizing up his opponent, and outplaying him. The pleasure in these pages is unwavering. But the second half, in which Bond tries to stop Drax from destroying London with a nuclear-armed rocket, is pretty silly.

The film adaptations frequently follow this pattern of starting out stronger than they finish, but there are plenty of exceptions to the rule. The movies are entertaining on a much bigger and resplendent scale than the novels, and they range in quality from exceptionally good to unbelievably awful. The initial Bond pictures improved on many of Fleming’s books, fixing plot holes and finding humor. The middle films devolved away from their source material, with mixed results. And the later entries strived to reboot the series into something applicable to times vastly different from the era that birthed the character.

The films enable a kind of virtual travel for moviegoers who rarely, if ever, get to visit any of the far-flung locations where 007's adventures take place. Like the books they’re based on, the movies take place in exotic countries far from England or the United States, showcasing performances by actors indigenous to those nations and featuring inventive action sequences built around the prominent landmarks of major foreign cities. These tantalizing glimpses of a wider world meant a lot in the 1960s, when air travel was more of a luxury. Even today, few could ever dream of seeing all the marvelous places Bond visits.

At their best, the Bond films are a stylish mix of fun and danger, not to mention a tongue-in-cheek commentary on both themselves and movies in general. Many of the pictures, especially those from the 1970s and 1990s, exhibit adolescent preoccupations, but plenty of them are far more dramatic and character-driven than their reputations suggest. The best in the lot have either a great villain or a great female lead, and often both. Even more than the 007 character, the outsized personalities of his counterparts, and the actors who portray them, are what make the movies so memorable. The caricature of a Bond villain is a larger-than-life madman with a palatial secret lair from which he can hatch and launch fiendish schemes for world domination. But most of the antagonists' goals are less loony, if still diabolical: smuggling, extorting, controlling the media, pitting governments against each other. And while some Bond girls deserve their reputations as vacuous sex objects, just as many are complex, independent women. All the female characters in the series exist in a male-controlled world: one we all inhabit. What make these women so compelling are the ways they manage to thrive in, escape, or otherwise transcend their situations. This doesn’t necessarily make them role models, but it does make them great movie characters.

Finding the line that delineates where the James Bond pictures are a reflection of societal sexism and where they perpetrate the attitude is more difficult than one might initially think. With some key exceptions, the most blatantly sexist films have also been the most popular, and therefore the ones that stick most firmly in our memories. But they represent less than half the overall output. The 1970s pictures aggressively pushed back against the growing power of feminism, which threatened and confused many men. And while the series enjoyed tremendous box office success during this time, these are the films that now appear the most embarrassingly dated. The strongest female characters are found in the films of 1960s—surprisingly, since we assume it to be the most chauvinistic period—and in the films of the new millennium, when the series found new footing by appealing to both its traditional young male demographic and a more mature and diverse audience.

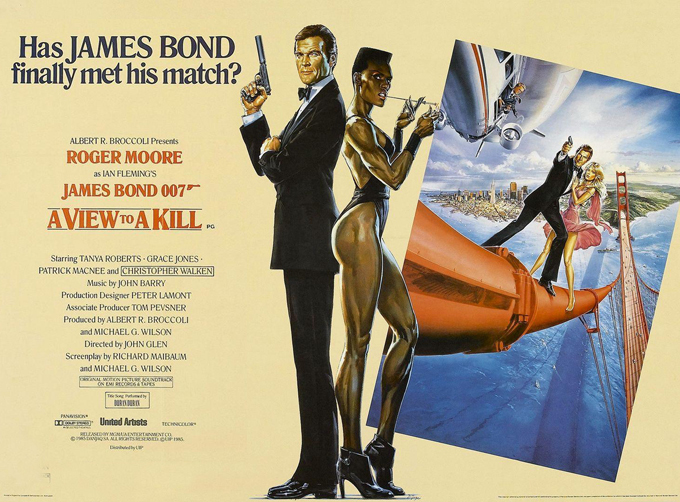

Of course, the ways in which these movies have been marketed and perceived in our collective conscious have always been unquestionably misogynistic. The term “Bond girls” itself was coined not by the filmmakers, but by tabloid journalists looking to sell newspapers and studio advertisers looking to drum up interest in each new release. Most of the lead female characters in the actual movies are far more nuanced than the scantily clad sex objects depicted on the posters, billboards, and magazine covers. But there is no question that the Bond pictures perpetuate an exaggerated male fantasy, not only with their abundance of beautiful, accessible girls but in the form of their violent yet principled hero. 007 is a man of contradictions. He's rough but sophisticated; a rebellious loner yet someone who belongs to the consummate clandestine team of a great Western superpower. He is a man caught between the bureaucracy of his government and the evil of those who wish to do harm to that government and the society it represents. Most moviegoers, not just men, get swept up in the escapism of a character who fights the good fight, overcoming tremendous odds, using his wits, bravura, and state-of-the-art technology. Throughout the decades, Bond has appeared all but indomitable—unlike his audience, and England, and America. This fantasy has sustained a cultural phenomenon longer than even its creators could have imagined.

This most British of series began at an opportune period in American cinema history. By the 1960s, US anti-trust laws were bringing about the demise of the Hollywood studio system. The resulting changes meant that independent producers were looking to finance films with international money for worldwide markets, which necessitated taking a fresh look at old assumptions about production and marketing. Since theaters were no longer restricted to the output of their parent studios and could now book whatever films they wanted, moviemakers from Europe found distribution in venues that had previously been unavailable to them. Freed by these emerging patterns of funding, development, and casting, the makers of the Bond pictures hit upon a formula that proved instantly lucrative and indefinitely replicable. The massive amount of money that the Bond films immediately began generating meant that more resources and talent could be poured into each new entry in the series, creating a buzz of audience expectation. Prior to Bond, sequels were mostly viewed with derision, and long-running film series for adults, like The Thin Man, Charlie Chan, or the Philo Vance mysteries, were rare. But after 007's success, the rest of the cautious and conservative industry caught up and realized that movie franchises could be both smart business and artistically satisfying.

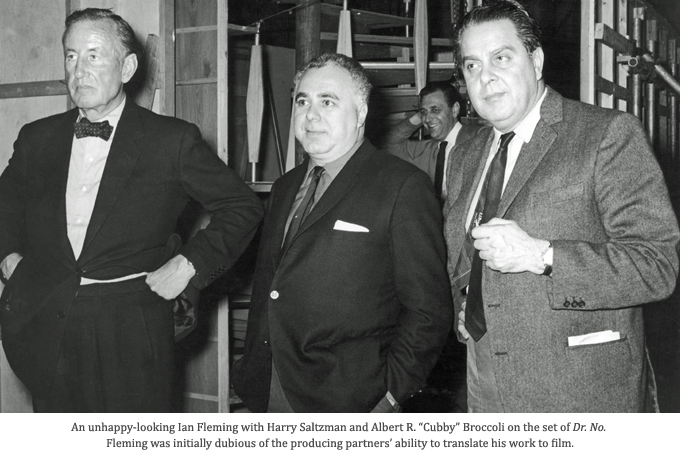

The triumph of the James Bond films is attributable to the seven individuals who came together to create the initial picture, Dr. No. The first two figures were Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli, respectively an ex-pat Canadian and ex-pat American living in England. A mutual friend who knew of their competing interests in Fleming’s properties introduced them. The two men seemed an unlikely pair. Broccoli was an experienced producer while Saltzman was a relative novice, and they had notable differences in personality that would bring them into conflict over the course of their partnership. But they were each smart enough to recognized they would have a better chance of long-term prosperity by combining their resources and acquiring the rights together. Within a week of their first meeting, Saltzman and Broccoli formed the production company EON (Everything Or Nothing). The following year, with most of the rights secured, they formed the holding company DANJAQ (named after their wives, Dana Broccoli and Jacqueline Saltzman). These entities were true family affairs. Both wives had a financial interest in the early productions and participated in much of the decision-making, and Broccoli’s daughter Barbara and son-in-law Michael G. Wilson would take over the lucrative family businesses in the 1990s.

In the 1960s, most film distribution companies with the capital needed to bankroll large-scale projects saw the James Bond material as risky, and the EON team initially had difficulty finding backing for their first project. American studios saw Fleming's novels as outlandish, overtly sexual, and simply too British. But United Artists, led by the wisest and most hands-off of all studio heads, Arthur Krim, took a risk and put up the budget for the first picture: one million dollars, a fairly modest sum even in 1962. Saltzman and Broccoli came from the “bigger is better” school of producing, and Dr. No would be their only Bond movie with a small budget. But given the producers' limited resources, the film represents a major achievement that has aged remarkably well.

The next two principal figures behind Dr. No’s success were its director, Terence Young, and its star, Sean Connery. Neither man was the first choice of the producers, who wanted Ken Hughes, Val Guest, or Guy Hamilton to direct and Cary Grant, David Niven, Patrick McGoohan, or possibly Roger Moore to play Bond. But Young, a dependable director who had worked with Broccoli before, was erudite, dashing, well groomed, and widely travelled, just like Bond himself. And when the producers chose the relatively unknown and (at the time) rather scruffy young Scottish actor to play 007, it was Young who took Connery under his wing and schooled him in the ways of an upper-class English gent. Many people involved in the production believe that the big-screen James Bond contained as much of Terence Young as Ian Fleming. There was also, of course, quite a lot of Sean Connery, who had considerable charisma and sex appeal. The young actor was far more impish than the solemn loner of Fleming’s novels, and these brash, insouciant qualities endeared him to audiences, who embraced the on-screen character of the cool but charming secret agent.

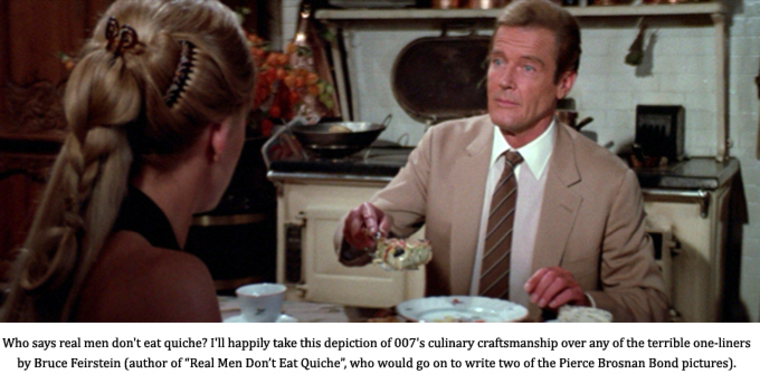

The fifth key figure was the prolific American screenwriter Richard Maibaum, a veteran Broadway actor and playwright who penned the 1949 version of The Great Gatsby and produced the fantastic 1948 noir thriller The Big Clock, as well writing as several early films for Broccoli. Maibaum wrote or co-wrote all but three of the first sixteen Bond pictures, and he contributed an American pragmatism that provided a balanced counterpoint to the wild flights of fancy that the British-based producers and directors encouraged. It’s telling that of the first sixteen Bond films, Maibaum had little to no involvement in the movies that faltered or devolved dangerously close to self-parody, and that every time the series righted itself after these stumbles, the script was authored solely by Maibaum or in conjunction with Broccoli’s son-in-law Wilson, whom Maibaum encouraged to become a screenwriter and with whom he wrote all five Bond pictures of the 1980s.

Dr. No’s editor, Peter Hunt, was the sixth crucial contributor. His stylistic sensibilities aligned seamlessly with the producers and directors. It's fair to describe many of the film craftsmen in England at that time as old fuddy-duddies, especially the editors and sound mixers, but Hunt, a seasoned but innovative film cutter, possessed a devilish sense of humor. He had a clear understanding of Young’s desire to give Dr. No an exaggerated, tongue-in-cheek feel, and this light approach to the material had the dual advantage of making the movie stand out while also appeasing the censors of the era. As Young correctly surmised, the filmmakers could get more of the story’s sex and violence past the powers-that-were if they played those aspects for laughs, rather than for pure dramatic effect. Through judicious cutting, sound mixing, and scoring, Hunt was able to push Young’s ideas even farther. He found all kinds of opportunities for humor in the post-production phase, as when he asked composer John Barry to create musical stings for each time Bond hits an approaching tarantula with his shoe. The audacious Hunt also gave the overall picture an unprecedentedly rapid tempo, thinking nothing of cutting several frames out of a shot if an actor didn’t shoot a gun or throw a punch fast enough. Even though this practice resulted in jump cuts, Hunt felt the jolts would make the action more exciting, and he knew how to use sound effects to smooth over the jarring transitions. The style and pace of Dr. No are major reasons why the movie holds up so well, more than half a century after its release.

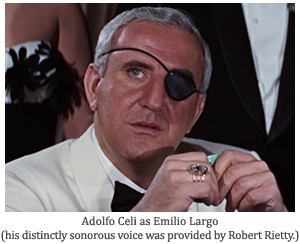

Hunt also supervised the dubbing of all the early films. Because these international productions prominently featured actors who spoke little to no English, the stars required additional actors to revoice their lines. Hunt’s casting and directing of these anonymous voice actors were crucial steps in the filmmaking process. Principal heroines and villains of the initial pictures, including Ursula Andress in Dr. No, Daniela Bianchi in From Russia with Love, Gert Fröbe in Goldfinger, and Adolfo Celi in Thunderball, all required overdubbing by English-speaking actors supervised by Hunt. If the vocal performances didn’t measure up to the physical ones, the films would have fallen apart, but Hunt always found the right voice actors to match the on-screen personalities. I saw these movies dozens of times before realizing that the voices I was hearing didn’t always belong to the actors I was watching.

Hunt was equally indispensable for his ability to cover continuity errors and plot problems through editing. Young tended to pay more attention to the cut of Sean Connery’s suit or the amount of handkerchief sticking out of the star's breast pocket than he did to making sure all the shots matched, and he was similarly not overly concerned with getting all the coverage needed to make a scene work. Hunt therefore directed a second unit to pick up material that Young didn’t have the time or inclination to shoot himself. Hunt also supervised re-shoots with the actors when script changes were made during the editorial process. He would even, at times, fabricate new shots by appropriating Young’s footage and altering it in an optical printer. Hunt was an editor far ahead of his time, the most unsung of the original James Bond creative team.

The last major contributor to the success of the series was the exceptionally talented John Barry, a former jazz trumpet player who became one of the most celebrated film composers of all time, creating exquisite soundtracks for Midnight Cowboy, Body Heat, Out of Africa, Dances with Wolves, Somewhere in Time, The Cotton Club, and dozens of other films. He was not credited as the composer of either Dr. No or the signature “James Bond Theme,” both of which were officially written by Monty Norman, but he did arrange, develop, and conduct these pieces, and he also provided the scores, songs, and orchestrations for eleven of the first sixteen Bond pictures. Barry, who was twenty-nine at the time, wrote and arranged with a youthful, raw, rhythmic energy that complemented Peter Hunt’s quick-and-dirty editing style. Hunt ended up inserting Barry’s variations on the “James Bond theme” throughout Dr. No, linking the music inextricably with the character. It's impossible to think of James Bond without thinking of Barry's music. And while his ‘60s themes are specific to the decade that gave rise to the series, his later scores feel as timeless as the Bond franchise itself.

These amalgamated talents created a series of films whose renown far surpassed that of the novels that were their source. But as with so many of cinema's greatest success stories, the artistic and commercial triumph of the Bond pictures has as much to do with timing as with the abilities of the people involved in their inception. The movies were produced and released in the early 1960s, when the youth of Great Britain was throwing off the austere attitudes of the post-war generation and embracing lifestyles of optimistic, pleasure-seeking excess. British bands like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones took American music and reinvented it, and much the same can be said of the first James Bond films. At the time, movies, like rock music, were a distinctly American export. But by loosening up the formulas, casting international stars, making the plots and set pieces more extreme, and adding an unmistakably English sense of humor, the men who made the Bond films were creating more stylish, action-packed entertainment, and beating the Americans at their own game.

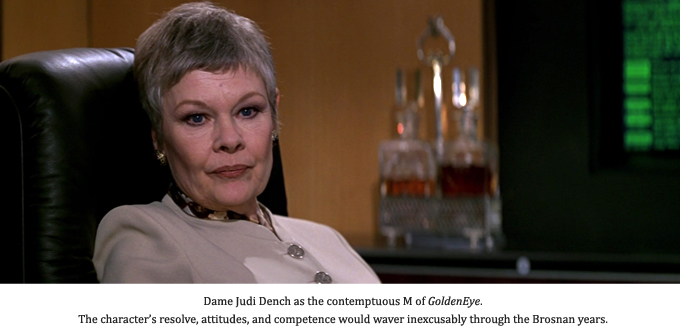

This voguish reimagining of familiar cinematic storytelling is the primary reason that the James Bond films of the 1960s are the best in the series. In the 1970s, Bond became campier, sillier, and more overtly self-conscious. The movies were still entertaining, but they lacked the cultural significance of their predecessors. While the 1980s pictures were more grounded and satisfying, the 1990s saw repeatedly unsuccessful attempts to make the character palatable to post-Cold War, post-feminist, post-politically correct audiences. (The attempts were unsuccessful in my opinion, that is; the box office receipts tell a different story.) In the first two decades of the new millennium, the franchise adapted once more, working to win for itself a new generation of viewers. After a shaky start, it has managed to achieve a triumphant return to artistic and cultural significance. Throughout these fluctuations in quality, from strong to weak, light to dark, groundbreaking to cliché, with many gradations in between, the box office remained robust. The roster of antagonists reflects the changing nature of threats faced by Western civilization, and the supporting players and cutting-edge technologies chronicle our society’s evolving conventions, tastes, subcultures, and attitudes. As a result, the series has managed not only to survive, but to maintain its value and relevance over an extraordinary span of time. The James Bond movies encompass a body of work that is thrilling to watch, study, and experience from different perspectives.

THE FILMS

Dr. No | From Russia with Love | Goldfinger | Thunderball | You Only Live Twice |

On Her Majesty's Secret Service | Diamonds Are Forever | Live and Let Die | The Man with

the Golden Gun | The Spy Who Loved Me | Moonraker | For Your Eyes Only | Octopussy |

The World Is Not Enough | Die Another Day | Casino Royale | Quantum of Solace | Skyfall

The first James Bond film remains one of the best, if not the best, of the series, despite its age and relatively small budget. Although it establishes the tone and style for many of the elements that would form the Bond template, it is more of a mystery thriller than a Cold War espionage tale. The heroic 007 is depicted more as a steely detective than as a globe-trotting secret agent. Bond's mission is to investigate the disappearance of a British officer in Jamaica, which leads to the discovery of a plot to interfere with the American space program.

Producers Saltzman and Broccoli had hoped to make Thunderball as their first James Bond picture, but the screen rights to that novel were tied up in a legal dispute between Ian Fleming and Kevin McClory, the first producer to try to bring Bond to the silver screen. It is just as well that the EON team didn't succeed, since the massive scale of Thunderball would have been unachievable on the $1 million budget that United Artists ponied up for the first production. Dr. No was a much better choice. The novel began as an idea for a TV series called Commander Jamaica that Ian Fleming was commissioned to write, after he had seemingly killed off James Bond in the novel From Russia With Love. When the TV series didn’t pan out, Fleming resurrected 007 and turned his Commander Jamaica script into the basis for his next novel, Dr. No. It turned out to be one of the most enjoyable reads in the series and ensured a future life for Bond in print.

The film opens with the signature gun barrel graphic created by Maurice Binder, who also designed the animated title sequence. Special titles were not yet commonplace in the early '60s, and Binder’s idiosyncratic credit sequences, which included all the opening titles from Thunderball (1965) to Licence to Kill (1989), are part of the series’ inimitable style. While Dr. No’s animated words and colored dots do not begin to rival Binder’s later sequences, in which the silhouettes of James Bond and bevies of naked women run, swim, fly, and perform gymnastics in an abstract playground featuring giant guns that shoot credits, it is still an attention-getting way to start a picture.

The writer originally hired by Albert Broccoli to adapt Fleming's novel was Wolf Mankowitz. The wild liberties he took with the material kept many of the best directors away. But Broccoli managed to convince his frequent collaborator Terence Young that the script would get sorted out by his next hire Richard Maibaum, and Young signed on as director. Harry Saltzman brought on Berkely Mather to do another script that was more “English” than what Maibaum devised, and Johanna Harwood to do the final polish and work with Young as the on-set scribe. Young claims that it was he, with Harwood’s help, who wrote the final draft, which adhered far more closely to the novel. Whatever the sequence of screenplay authorship, the final version of Dr. No is a faithful adaptation of Fleming’s excellent book. Fleming was alive at the time of the film’s production, and he hoped that his close friend Noel Coward would play either Bond or the titular villain, but Coward’s characteristically whimsical reply to Fleming’s letter of request read simply: “Dr. No? No, No No!”

At the time they were cast, the movie’s lead actors were essentially unknowns, which is part of what made the picture feel so fresh. Sean Connery’s biggest credits to date were for co-starring in the enchanting live-action Disney film Darby O'Gill and the Little People and the forgettable melodrama Another Time, Another Place. He also played minor roles in the British movies A Night to Remember, Hell Drivers, and Action of the Tiger (which was directed by Terence Young). A young Jack Lord, who went on to star in the TV show Hawaii Five-0, plays Bond's ally Felix Lieter, an American CIA agent. Lord, with his white suit and jet-black Ray-Ban sunglasses, is still the coolest actor to take on this role. Joseph Wiseman is appropriately sinister as the half-German, half-Chinese Dr. Julius No. But aside from Connery it is the women in this first production who really stand out. Of these three “Bond girls,” only one fits the common stereotype.

It is impossible to think of either Eunice Gayson or her character Sylvia Trench as a mere bimbo for Bond to toy with. Trench was intended as a recurring part of the series, the steady girlfriend to whom 007 would always be saying good-bye at the top of each film before jetting off to whatever exotic country his mission called for. According to interviews with Gayson, the plan was eventually to set a movie in England in which Trench would be Connery’s leading lady. But this notion was abandoned when Terence Young dropped out of directing Goldfinger, and Sylvia Trench wound up appearing in only the first two pictures.

We meet 007 for the first time through the character of Sylvia Trench: she is admiring his luck at the baccarat table in a swanky nightclub. This iconic introduction sets Bond up as the ultimate sophisticated English gentleman, wearing tailored clothes and deftly playing cards while casually lighting a cigarette from his gunmetal case. It is a nod to Bond’s introduction in Fleming's first novel Casino Royal, but the scene is shot in an even more distinguished manner. At first, we only see Bond from the back, and it takes a while before we get a glimpse of his face. Director Young claimed he was riffing on the 1939 film Juarez, in which director William Dieterle introduced Paul Muni in a similar way. Young apparently found Dieterle's slow build up rather pretentious and mocked it with his own protracted reveal. But whether this presentation is an advantageous steal or a sly inside joke, the minute we see Sean Connery introduce himself as “Bond . . . James Bond,” and we hear John Barry’s music begin to underscore the moment, we know we are in for a good time. This immortal introduction has aged marvelously. The expert linking of a protagonist to his theme music, as Bond exits the casino with the alluring and aggressive Trench, is one of the key reasons this film is such a classic.

The second Bond girl in Dr. No is Zena Marshall’s Miss Taro, who lures 007 into a potentially lethal car chase. Although Taro is the least important of the film’s three leading ladies, she holds the distinction of being the only woman to spit in James Bond’s face (at least on screen). As a seething and aggressive gesture, it anticipates the feelings of many future women characters that interact with Bond over the next fifty years.

The most imposing actress and the most indelible female part in Dr. No—and arguably in all of the Bond films—is Ursula Andress's Honey Rider. This character, which Fleming had named with one of his typical sex puns, is a resourceful and fiercely independent beachcomber who becomes entangled in Bond’s mission. Rider is less worldly than Bond, but she is very much his equal in terms of intelligence, resourcefulness, and sex appeal. The movie shifts gears dramatically when she and Bond meet. Andress’s introduction at exactly one hour into the picture is every bit as revered as Sean Connery’s at the beginning. The legendary director and estimable raconteur Orson Welles once commented that the two greatest entrances in all of cinema history were Omar Sharif’s in Lawrence of Arabia and Ursula Andress’s in Dr. No. It isn’t just that she looks so striking in a white bikini with a giant knife strapped across her waist, it is how her first appearance changes the dynamics of the film. At this point in the story, she is the last thing Bond (and the audience) expects to see. The fast-paced picture stops and lingers on her when she emerges from the ocean like Botticelli‘s Venus, humming Monty Norman’s “Underneath the Mango Tree,” with the sun glistening on her long, wet, blonde hair. A film can’t spend the kind of time on backstory that a novel can, and the movie version of Honey Rider is not the exotic, broken-nosed, almost feral character that Ian Fleming envisioned. But the screenwriters manage to give Andress an excellent scene in which Rider tells Bond about her life.

Two other fine actors in the movie are Anthony Dawson and John Kitzmiller. Dawson, a Scottish bit player best remembered for his role as the killer in Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder, was a favorite of Terence Young and appears in nearly all of the director’s pictures. In From Russia with Love and Thunderball, his hands depict those of the unseen evil genius Ernst Stavro Blofeld. In Dr. No, he plays Professor Dent, Dr. No’s sinister but weak-willed henchman. Kitzmiller, an African-American actor who moved to Italy after serving there in WWII, was a veteran of over fifty European films including Fellini's neorealist classic Without Pity. Here he plays Quarrel, a Cayman Islander who becomes Bond’s right-hand man. Quarrel is the first in a long line of characters whom some fans call Bond’s disposable helpers or sacrificial lambs. As a result of assisting 007, these endearing individuals suffer violent deaths in the second acts of many films in the series. But the dismissive monikers are unfair. Quarrel, like many of the sidekicks to come, is anything but disposable or lamb-like, and his death, both in the novel and the movie, gives us our first glimpse of Bond's emotional and physical vulnerability.

This film also inaugurates many of the recurring roles in the series, including Bond’s Secret Service Chief, known only as M and portrayed by the wonderful English character actor Bernard Lee (The Third Man, Beat the Devil), and M’s secretary Miss Moneypenny, played by the lovely Lois Maxwell. Maxwell’s playful banter with Connery, which always hinted at a fondly remembered long-ago fling between their characters, was so charming and successful that she carried on in the role in fourteen consecutive films. Peter Burton plays Q, the MI5 armorer. Burton could have had a job for life if he had wanted to continue in the role. Instead, he turned down From Russia with Love and was replaced by Desmond Llewelyn, who would appear as Q in sixteen subsequent pictures.

The cast and crew work magnificently together, and the stylish blend of exotic location shooting and virtuoso British studio work dazzles the eyes and ears. One invaluable member of the Dr. No production team who should not go unmentioned is the German art director Ken Adam. Adam’s ingenious sets, as much as Peter Hunt’s editing and Terence Young’s direction, make the early Bond pictures stand out among other impressive but more conventional adventure films of the period, like John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven, J. Lee Thompson’s The Guns Of Navarone, and Howard Hawk’s Hatari!. Adam’s large, sparse rooms, which combine modern technology with old-fashioned furnishings, gave the picture a look unlike anything seen before in movies. Adam also knew how to stretch the limited budget of the first film, making it appear far more expensive than it actually was. For example, in the scene in which Professor Dent receives orders from Dr. No to kill Bond with a tarantula, Adam’s highly stylized yet cost-efficient two-wall set with its grated ceiling and undersized chair, gives the professor the look of a tiny insect trapped in a spider’s web. Adam would go on to design seven of the most visually magnificent James Bond pictures of the '60s and '70s, as well as two more of the movies in my Top 100 Favorites: Jacques Tourneur’s Night of the Demon, and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove—which was Adam's next assignment after completing work on this picture.

Dr. No is a legendary movie that inaugurated one of the most celebrated and long-running international film series of all time. But it’s also enjoyable when viewed as the hastily produced, low-budget B-movie that it is. Shot mostly in Jamaica—not a place where films are commonly made—it has the winningly ragtag aesthetic of a little picture made by a small group of enthusiastic and unified people. You can tell that Sean Connery is always driving his car himself, even in distance shots which would normally use a double, and you get the feeling that cinematographer Ted Moore and director Terence Young are behind the camera at all times, rather than farming out major shots to second units. It is the only James Bond film that has this quasi-indie vibe, and watching it gives you the distinct sense that it must have been incredibly fun to make. While the movies got bigger and more extravagant as the series went on, they rarely, if ever, bested this one.

The second James Bond picture, made one year after Dr. No by mostly the same production team, improved on many aspects of the first. Though still larger than life and tongue-in-cheek, From Russia with Love is the most straightforward of 007’s cinematic adventures, playing almost like a John le Carré spy story that happens to indulge in a few amusing flights of fancy. It is based on one of the best of the Fleming novels, features two of the most entertaining villains in the entire series, and stars Sean Connery in his most confident and commanding performance.

Fleming’s novel, the fifth in the series, is inventively structured, with the first third of the book devoted entirely to the agents of SMERSH, the Soviet counterintelligence service that appears in several 007 novels. The reader learns all about the story’s villains and heroine before James Bond even makes an appearance. This sequencing would not suit the producers of From Russia with Love, who were eager to make a star out of Sean Connery, so the film follows the same basic structure as Dr. No. But screenwriter Richard Maibaum manages to work almost every noteworthy sequence from the novel into the movie, in addition to making a number of major improvements to the narrative.

One such change involves replacing SMERSH with the international terrorist organization SPECTRE, which Fleming did not introduce until Thunderball, his ninth Bond novel. Broccoli and Saltzman had hoped to make Thunderball as their first James Bond picture, but when that proved impossible they took the concept of SPECTRE and added it into Dr. No, figuring that setting up the fictional organization in this film would pay off if they were eventually able to make Thunderball. Also, by the time From Russia with Love went into script development, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and Great Brittan was thawing. The filmmakers saw political and narrative advantages in making the principal antagonist in this second movie SPECTRE rather than SMERSH, and having the terrorist network toying with the two great powers of East and West strictly for its own pleasure and profit.

One such change involves replacing SMERSH with the international terrorist organization SPECTRE, which Fleming did not introduce until Thunderball, his ninth Bond novel. Broccoli and Saltzman had hoped to make Thunderball as their first James Bond picture, but when that proved impossible they took the concept of SPECTRE and added it into Dr. No, figuring that setting up the fictional organization in this film would pay off if they were eventually able to make Thunderball. Also, by the time From Russia with Love went into script development, the Cold War between the Soviet Union and Great Brittan was thawing. The filmmakers saw political and narrative advantages in making the principal antagonist in this second movie SPECTRE rather than SMERSH, and having the terrorist network toying with the two great powers of East and West strictly for its own pleasure and profit.

The story of SPECTRE’s plan to steal a Russian cryptographic device and sell it back to them while at the same time exacting revenge on James Bond is a more complex narrative than the one in the novel. It is also more credible, since Fleming’s original conception of this plot being hatched by the Russian Secret Service is farfetched, and it’s also more fun. The formidable villains of the book lose none of their prowess when overseen by the mysterious Blofeld, the mastermind behind SPECTRE. These villains are the sinister SMERSH colonel Rosa Klebb and the brutal assassin Donald "Red" Grant. The infamous Austrian singer and actress Lotte Lenya (iconic star of her husband Kurt Weill’s Socialist masterpiece The Threepenny Opera) plays Klebb. Relishing the role, she embodies every bit of the 1960s stereotype of an evil lesbian Soviet agent. She's a squat, slimy, almost reptilian creature in an uncomfortable looking military uniform. Lenya’s portrayal of the harsh, heartless Klebb, with her braying voice, brass knuckles, and poisoned switchblade shoes, set her apart from the suave and sophisticated villains of the Bond series. It is a memorable role made all the more masterly by its limited screen time.

The English actor and playwright Robert Shaw plays Red Grant. Shaw, later known for his signature performances in A Man for All Seasons, The Sting, and Jaws, is so young and fit in this movie that he seems like he could kill Sean Connery just by looking at him. Shaw’s physical prowess, along with his chiseled, masculine attractiveness make him an exciting antagonist, and his clash with Bond on the Orient Express is arguably the most outstanding fight sequence in the entire series.

The revered Mexican-American actor Pedro Armendáriz, star of John Ford’s films The Fugitive, Fort Apache, and 3 Godfathers, plays Bond’s Turkish ally Ali Karim Bey. Armendáriz is one of the most appealingly macho actors to appear in a Bond picture. His warm, humorous presence lights up the screen in all of his scenes. Ironically, Armendáriz was in terrible pain while shooting in Istanbul and was diagnosed with inoperable kidney cancer during filming. It is believed he contracted the disease in the same way as John Wayne, Agnes Moorehead, and Dick Powell did, by working on the 1956 epic The Conqueror, which was shot downwind from the site of America’s aboveground nuclear weapons tests in Nevada. A great admirer of Ernest Hemingway's decision to shoot himself rather than to waste away in a deathbed, Armendáriz committed suicide with a gun once his scenes were finished, confident that his participation in From Russia with Love would secure his family’s financial future. In the few retakes that were necessary, director Terence Young stood in and doubled for the late actor.

As Bond’s love interest, Daniela Bianchi was just 21 years old when she played Soviet Embassy clerk Tatiana Romanova, who is engaged by SMERSH to entrap 007. She's the youngest actress to play the female lead in the series, which makes her character’s naiveté all the more convincing and charming. Bond first meets her when she turns up naked in his hotel room bed, one of the key episodes in the movie, and it features one of the most overtly sexual double entendres in the entire series. The line comes across as a fairly subtle joke since Connery delivers it without any overt mugging to the camera and it slipped right past the censors of the day.

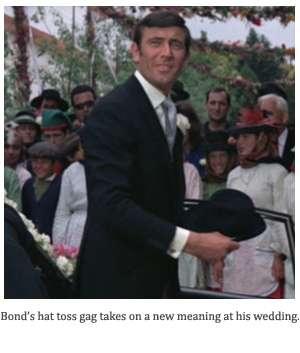

Bernard Lee, Lois Maxwell, and Eunice Gayson all return in their roles from Dr. No, and Desmond Llewelyn makes his first appearance as Q. Llewelyn would continue on as the beleaguered armorer in seventeen films—more than any other actor in the series. But it is Connery who owns this picture. From Russia with Love showcases his best performance as 007. He is cooler and more self-assured than he was in Dr. No, but not yet bored with the character, as he seems to be in some of his later outings. His ruthless side is on full display, as he slaps several people in the face and shoots his enemies in cold blood, but he is also tender and sensitive in many moments with Bianchi. Early in the film, Bond walks into his Istanbul hotel room and catches himself in the act of dropping his hat on the bed. He hesitates for a second, aware of the superstition, and then aggressively tosses the hat squarely onto the bed as if daring the bad luck to take him on. It is non-verbal moments like this one that make his performance and this picture so stimulating and endlessly re-watchable.

The James Bond formula fully gelled in Goldfinger, the first movie to possess nearly all the components people associate with a 007 picture. It does lack a few key ingredients, however, most notably an exotic, far-way setting—the film was intended to be a blockbuster aimed squarely at the US market, and accordingly much of it takes place in American locations like Miami Beach and Kentucky. While many consider Goldfinger the best Bond movie and a cinematic classic, it also contains an abundance of the series' least appealing facets, including misogynistic overtones, painfully overt jokes and gags, Bond's reliance on gadgets and gimmicks rather than wits and strength, and the uninspired casting of certain supporting roles. Most of these drawbacks are more odious to contemporary viewers than they were to audiences in 1964 and are outweighed by a well-crafted script and some stand-out performances. The producers had hoped to score Orson Welles for the title role, which would have been wonderful, but he wanted too much money. (Welles would go on to play the Bond villain Le Chiffre three years later in Casino Royale, Charles K. Feldman’s nearly-unwatchable James Bond spoof, when the cash-strapped auteur had become less choosy about the acting roles he was willing to take.) Instead, Broccoli and Saltzman hired German actor Gert Fröbe after they saw him portray a child molester in the film Es geschah am hellichten Tag. The fact that Fröbe spoke no English was of little concern to them, as he looked ideal for the role.

For Goldfinger's henchman Oddjob, director Guy Hamilton cast the Korean Olympic weightlifter Harold Sakata after seeing him win a wrestling match. Fascinated by the way Sakata moved, Hamilton incorporated many of the large man’s attributes into the character. Though Oddjob has no lines in the picture, he too makes one of the most indelible impressions of all the Bond villains. As distinctive, twisted, and potent adversaries to 007, Goldfinger and Oddjob are, perhaps, second only to Rosa Kleb and Red Grant in From Russia with Love.

As in Dr. No, three Bond girls grace Goldfinger: two minor roles in the first half, and one more substantial one in the second. Shirley Eaton has the smallest but most iconic part as Jill Masterson, a gorgeous young woman who works for Goldfinger in various capacities. We don’t know if she's in thrall to Goldfinger or if she is using the big man as much as he is using her, but either way, she’s no bimbo. Jill Masterson represents an important, though often dismissed type of Bond girl. She may be trapped under the thumb of a powerful man, but she is as smart, self-interested, and sexually aggressive as James Bond himself. When she helps him spoil Goldfinger’s card cheating scam, the villain has her killed and covered in gold paint. Her glittering corpse became the main image of the film’s marketing campaign and one of the most striking in the series. Tania Mallet is neither as skilled nor as attractive an actress as Eaton, but her character Tilly, Jill's avenging sister, is well-written, and Mallet is able to hold her own with Connery.

Honor Blackman deftly takes on the most memorably named Ian Fleming creation of all time: Pussy Galore, Goldfinger’s personal pilot and accomplice. Blackman is five years older than Connery and, at thirty-nine, was the oldest actress to play a Bond girl until fifty-one year-old Monica Bellucci in the 2015 film Spectre. Blackman was a major star in England from the television series The Avengers. Delighted to undertake this part, she particularly relished bringing up her character’s name to dignitaries and members of the press whenever possible. The producers feared they might have trouble getting the name past censors, but when a London newspaper ran a picture of Blackman and Prince Charles with the caption “Pussy and the Prince,” all concerns instantly vanished.

In Fleming's novel, Pussy Galore is a tough, butch gangster who runs an all-lesbian Harlem crime syndicate called the Cement Mixers. For the film, the more extreme aspects of her personality had to be toned down, but we get a few hints about her sexual orientation, not the least in her illustrious line to Bond: “You can turn off the charm, I’m immune.” After sparring with Pussy in a hay-barn, Bond forces himself on her until she submits. Many found this notorious episode objectionable at the time, and even more do now. While the scene is a little cringe-worthy, Pussy Galore is a woman whose interests and desires are established as running the gamut. It is therefore not inconceivable that she might fancy both a fight and a sexual tryst with James Bond, or that she might find it strategic to choose to switch her allegiance from Goldfinger to 007. Nevertheless, many critics of the era called out the film for implying, via this scene, that Bond’s sexual magnetism is so supernaturally powerful that he can turn a lesbian straight—something the writers of the next picture, Thunderball, would amusingly address with the character of Fiona Volpe.

Bernard Lee, Lois Maxwell, and Desmond Llewelyn all return as the MI5 staff. Llewelyn, as Q, steals the show when he explains the “rather special modifications” of the Aston Martin DB5 car that has been specially prepared for 007, which include machine guns, an oil slick, an ejector seat, and, with great prescience, a GPS device. The scene in Q’s lab became a staple of the series henceforth, and James Bond’s car became as famous as the character himself. The rest of the supporting cast is less successful, especially Cec Linder as Bond’s CIA buddy Felix Lieter. Linder, who seems about twenty years older than Connery, took the part when Jack Lord demanded equal billing and a larger salary to reprise the role. It is too bad the filmmakers didn’t just find a Jack Lord lookalike, as they did in the next picture.

Terence Young, who oversaw the first two Bond outings, chose to make The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders over Goldfinger, so Broccoli and Saltzman turned to Guy Hamilton, one of their original first choices to direct James Bond. Hamilton would go on to do three other Bond pictures, and not three of the strongest. He tends to exaggerate too much and overplay the humor, although he does come up with some adroit comic touches in Goldfinger worthy of Alfred Hitchcock—such as a scene at a gate house when a little old lady bows, scrapes, and smiles at Bond in one moment and returns blasting a Tommy gun at him in the next.

The film was budgeted at three million dollars, the cost of the first two pictures combined, but it looks sloppy and piecemeal. Though Ken Adam’s sets are magnificent, much of the movie’s connective tissue feels tossed together at the last minute by editor Peter Hunt. The heavy use of doubles, back projection, redubbing, and other post-production techniques stand out less forgivably in this spectacular, higher-budget picture than in the first two comparatively modest movies.

The film was budgeted at three million dollars, the cost of the first two pictures combined, but it looks sloppy and piecemeal. Though Ken Adam’s sets are magnificent, much of the movie’s connective tissue feels tossed together at the last minute by editor Peter Hunt. The heavy use of doubles, back projection, redubbing, and other post-production techniques stand out less forgivably in this spectacular, higher-budget picture than in the first two comparatively modest movies.

The novel Goldfinger is one of the better books in the series. Fleming delves more deeply into Bond's psychology than he had in any story to date, in addition to dreaming up a dastardly villain and some gripping set pieces. Screenwriters Paul Dehn (author of the scripts for The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, Murder on the Orient Express, and all the Planet of the Apes sequels) and Richard Maibaum dispense with the psychologically complex, internal aspects of the character, but they also fix huge holes in the novel’s absurd narrative, which concerns Goldfinger's plot to steal all the gold in Fort Knox.

This well-structured film contains perhaps the most absorbing first act in the entire series. James Bond meets the main villain twice during the first half hour, which is quite unusual. The early golf sequence, in which Bond and Goldfinger play a leisurely eighteen holes and 007 tempts his nemesis with a bar of Nazi gold, is one of the true joys of the picture. Though I’m not a golfer, even I get sucked into the idea of the game when watching this beautifully-constructed and photographed sequence. It was while shooting this movie that Connery developed his passionate and enduring love for the sport, and it’s hard to blame him.

Forty minutes into the picture, Bond seems to have solved the mystery and completed his mission, until he stumbles onto a much more elaborate plot after being captured. The sequence in which Goldfinger threatens to slice a bound Bond in half with a laser beam is yet another revered scene in this classic film, and it contains the most celebrated verbal exchange between 007 and a baddie. The first half of the movie, which also includes a high-octane pre-credit sequence and a car chase where we see the tricked out Aston Martin in action, is so chock full of unforgettable and beloved moments that it’s no wonder this picture is so many people's favorite. But the second half doesn’t quite live up to what comes before it. While it has dozens of great moments, among them Goldfinger’s explanation of his master plan and the outlandish Fort Knox climax, the humor and goofiness undercut their potency, and they don't hold up as well upon multiple viewings. This film, more than Dr. No, established the big action sequence climax of the Bond formula, complete with a ticking bomb, hundreds of extras in army uniforms or matching jumpsuits, and a nail-biting confrontation with an impossibly muscular henchman. Indeed, Bond’s mano a mano with Oddjob inside the golden fortress is thoroughly satisfying. The restrained tension of this small fight helps to ground the wild silliness of the larger battle outside. Still, this big action climax can’t touch the golf sequence as an outstanding piece of cinema.

Goldfinger was the first Bond movie to be scored entirely by John Barry, whose first swing at a theme song became the undisputed greatest of the entire series, not to mention one of the most lionized title tunes in all of cinema. The instrumentation is raw and raunchy and prominently features brass instruments to accentuate the metallic nature of the villain’s obsession. Barry and lyricist Anthony Newley drew inspiration from Kurt Weill and Bertold Brecht’s villain song, “Mack The Knife,” from The Threepenny Opera. Shirley Bassey's aggressive vocal permanently sealed the song into both film and music history. This Bond title song is one of the only ones that is still frequently played and performed today.

The third 007 picture turned out to be the massive hit the producers were hoping for, and it fully activated and inspired James Bond mania all over the globe, especially in the US. The first two films were re-released worldwide and proved to be tremendous successes, while Desmond Llewelyn and the Aston Martin went on an international tour, drawing droves of people who wanted to see James Bond’s car up close. Ian Fleming, sadly, did not live to see the series become a phenomenon. The life-long smoker and heavy drinker died of a heart attack at age 53, before Goldfinger was released.

In 1959, producer Kevin McClory hoped to be the first man to bring James Bond to the silver screen. He and screenwriter Jack Whittingham collaborated on a script with Ian Fleming with the working title James Bond, Secret Agent. But after the lackluster reception of McClory’s movie The Boy and the Bridge later that year, Fleming got cold feet about their collaboration. When the James Bond, Secret Agent picture (also known by the title Longitude 78 West) began to fall apart, Fleming did what he had done with other failed television and film projects: he adapted the unused screenplay into his next James Bond novel. But when Fleming wrote the book, which he named Thunderball, he neither consulted his former collaborators nor gave them any credit as co-authors. Accordingly, McClory sued Fleming shortly after Thunderball’s publication. The eventual settlement ensured that subsequent editions of the book would credit McClory and Whittingham, and it awarded McClory control over the screen rights.

Saltzman and Broccoli feared having any rival Bond films made from the two titles they did not control, Thunderball and Casino Royale. So as soon as McClory’s lawsuit was settled, they decided to bring him into their fold and make Thunderball with McClory serving as producer and themselves as executive producers. As part of their deal, McClory would retain the screen rights to the novel, with the provision that he not remake the film for a period of at least ten years. It would take nearly twenty years for a Thunderball remake to come to fruition, as Never Say Never Again (1983), for which McClory was able to lure Sean Connery back for one last performance as 007.

Terence Young, who had directed the first two James Bond pictures, returned to direct the fourth. Young always said his favorite Fleming novels were Thunderball, From Russia with Love, and Dr. No, and they were the three he ended up making, albeit in reverse order. The scale of this film is enormous compared to the first three movies, and the running time substantially longer. Though somewhat bloated, it doesn’t feel overly-ambitious and its tone is much more in line with the first two movies—still playful and over the top, but far less goofy than Goldfinger.

The novel returns James Bond to Fleming's best-loved location, Jamaica, but first the macho secret agent is sent by M to a trendy health clinic in the hope of breaking him of some nasty habits—mainly the heavy drinking and smoking, vices to which Fleming was also addicted. Screenwriters Richard Maibaum and John Hopkins make the most of Fleming's lively first chapters and turn one of the most enjoyable reads in the Fleming catalogue into one of the better James Bond screenplays.  The plot, in which the villainous SPECTRE organization steals two nuclear warheads and uses them to hold the United States and England hostage for ransom, makes for an adventure story on a much larger scale then most of the other novels. Maibaum and Hopkins are able to make better use of key connections between the characters than Fleming does in the novel. For example, the mastermind behind the SPECTRE plan, Emilio Largo, uses the brother of his lover Domino to hijack a plane carrying the warheads. Domino’s relationship to the pilot, whom Bond remembers seeing during his time at the health clinic, is what enables 007 to uncover much of the information he needs to foil the caper. The screenplay is defter in its use of the innocent Domino’s various attachments to the sinister characters involved in the hijacking and ransom. However, there are several memorable moments in the book that don’t survive the transition to film because they are too overtly sexual for the standards of the era.

The plot, in which the villainous SPECTRE organization steals two nuclear warheads and uses them to hold the United States and England hostage for ransom, makes for an adventure story on a much larger scale then most of the other novels. Maibaum and Hopkins are able to make better use of key connections between the characters than Fleming does in the novel. For example, the mastermind behind the SPECTRE plan, Emilio Largo, uses the brother of his lover Domino to hijack a plane carrying the warheads. Domino’s relationship to the pilot, whom Bond remembers seeing during his time at the health clinic, is what enables 007 to uncover much of the information he needs to foil the caper. The screenplay is defter in its use of the innocent Domino’s various attachments to the sinister characters involved in the hijacking and ransom. However, there are several memorable moments in the book that don’t survive the transition to film because they are too overtly sexual for the standards of the era.

Adolfo Celi’s Largo continues the tradition of villains who are simultaneously amusing, imposing, charming, and deadly. Like Gert Fröbe, Celi’s voice is dubbed by another actor, which gives Largo a distinctively understated, almost whispered, style of speaking his disquieting dialogue. Desmond Llewelyn returns as Q who, in an unusual change of structure, travels to equip Bond in the field. Even more than in Goldfinger, in Thunderball the amusing and irreverent relationship between the two characters becomes firmly established.

Adolfo Celi’s Largo continues the tradition of villains who are simultaneously amusing, imposing, charming, and deadly. Like Gert Fröbe, Celi’s voice is dubbed by another actor, which gives Largo a distinctively understated, almost whispered, style of speaking his disquieting dialogue. Desmond Llewelyn returns as Q who, in an unusual change of structure, travels to equip Bond in the field. Even more than in Goldfinger, in Thunderball the amusing and irreverent relationship between the two characters becomes firmly established.

Broccoli hoped to land Julie Christie, Raquel Welch, or Faye Dunaway as his leading lady, but none of them panned out, and he eventually narrowed down his search to the French beauty queen Claudine Auger and the Italian actress Luciana Paluzzi. In the end, both were cast. Auger plays Largo's mistress Domino with strength and tenderness, unaware of the extent to which the villain is manipulating her. Her Domino is a smart, damaged, and sympathetic Bond girl whose eventual union with 007 does not seem like a foregone conclusion, as is so often the case in this series. Paluzzi, for her part, is one of the film's high points, as the fiery and voluptuous SPECTRE agent Fiona Volpe. Volpe is the most compelling and amusing of all the villainous Bond girls. Physically imposing, verbally sharp, and sexually aggressive, she is every bit James Bond’s equal. In one of her best lines she mocks 007's supposed ability to win women over by the sheer power of his irresistible sexuality. In doing so, she uses dialogue that quotes verbatim from one of the most scathing critical reviews of Goldfinger. This type of unobtrusive inside joke—which takes nothing away from the drama of the scene—is an example of Terence Young’s skill at creating entertainment that works on multiple tiers. Later directors in the series would be less successful at finding this balance between credible storytelling and winking at the audience.

The third Bond girl in Thunderball also discredits 007’s presumed magical ability to seduce any woman he wants, though in a manor more unfortunately true to life. Molly Peters plays Patricia Fearing, a physiotherapist at the health clinic in the early section of the film. Fearing finds Bond a boorish pest who won’t take her, or the therapy she’s trying to administer, seriously. She fiercely rejects his numerous sexual advances. In the end, the only way Bond can have his way with her is through implied blackmail and taking her by force. It’s all played for laughs, but is undoubtedly the most flagrant act of brutal misogyny in the entire series. Fearing doesn’t instantly melt into a tamed, adoring sex kitten sighing, “Oh James,” after the encounter—in fact she gets in a few potent verbal jabs at Bond in their next sequence together—but by her final scene, the transformation is complete. She bids Bond farewell telling him she’d love to see him again, “any time, any place.” The line is another inside joke, referring to Connery’s earlier film Another Time, Another Place, but it firmly establishes the attitude that women who say “no” will eventually come around to “yes” even if it requires force. This perspective is reflective of the times the film was made, but is certainly guilty of perpetuating and reinforcing the unacceptable notion because, by now, Bond was such a major masculine hero whom men in the audience wanted to emulate. Far more than the much discussed and debated fight-turned-love scene with Honor Blackman in Goldfinger, the sequence with Molly Peters in Thunderball stands as the true misogynist legacy of the screen incarnation of James Bond.

Thunderball was the first James Bond picture to be shot in the 2.35:1 widescreen aspect ratio, which contributes to its epic texture. In addition, John Barry went all out with his musical score, including a title song with a high note that pop superstar Tom Jones holds for so long that he reportedly fainted during the recording session. Maurice Binder returned for the opening titles, which feature his signature silhouettes of Bond, naked women, and lots of guns, as would the titles of the next twelve movies in the series. Here, Bender's girls are swimming and shooting harpoon guns, which is appropriate since nearly twenty-five percent of Thunderball takes place underwater. All that undersea action makes the film unpopular with many fans and critics like Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, who complain that it is slow, boring, and frustrating, in the sense that it’s difficult to distinguish the good guys from the bad guys when all the actors' faces are obscured by masks and diving gear. While these underwater sequences are a bit indulgent, they are visually breathtaking and quite advanced for a picture of this vintage. And for anyone confused by who's fighting who, here's an easy way to tell the difference: the good guys wear orange wetsuits, and the bad guys wear black ones.

Thunderball cost as much as all three of the preceding movies combined, but the investment paid off: adjusted for inflation, it is still the highest-grossing James Bond picture, not to mention the twenty-seventh biggest box-office hit in all of film history. The production, however, marked a turning point in the attitude of the man in the starring role. Although Sean Connery called his performance in Thunderball his best in the series, the constant attention from press and admirers made shooting unpleasant. He began to tire of the role that made him famous. He wasn't even sure he liked being such a huge star in the first place. After Thunderball, Connery began to make noises about being fed up with the whole Bond enterprise. However, he would return to the role in the following film, and for two more movies, before finally calling it quits.

Saltzman and Broccoli had planned to make On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as their fifth James Bond film, but Switzerland’s unusually warm weather in 1966 meant a problematic lack of snowy mountains for that production. Knowing this, the producers hastily removed the traditional teaser line of text that ended their films (“James Bond will return in . . . ,” followed by the title of the next novel they planned to adapt) from the end credits of Thunderball just before it was released. Instead of the Swiss-set On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, they decided that You Only Live Twice, which takes place in Japan, would be made next. Richard Maibaum, who had co-written all of the prior James Bond films and had nearly completed his screenplay for OHMSS, was unavailable to generate an entirely new script on such short notice, so the producers hired Harold Jack Bloom (The Naked Spur).

Unhappy with Bloom's work and with an increasingly pressing need for a script, they turned to, of all people, the notoriously prickly British writer Roald Dahl (author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach, Matilda, The Witches, Fantastic Mr. Fox, My Uncle Oswald, and countless other novels and short stories). Why Dahl, who had never before worked on a screenplay, would be entrusted with the Bond legacy is a bit of a mystery, other than the fact that he was a friend of the late Fleming and shared his background in intelligence work during World War II. However, Dahl considered You Only Live Twice to be Fleming’s worst novel, dismissing it as a glorified travelogue with no plot. For his screenplay, Dahl cannibalized many elements of Dr. No, including a single exotic setting, a SPECTRE attack on the US space program, a villain with a fantastic secret lair in which he explains his fiendish scheme to James Bond, the one man he considers capable of appreciating his genius, and three Bond girls: an ally and an enemy who each get killed off in the first half, and a lead who winds up with 007 in the end.

There are numerous seemingly Dahlesque details to the movie. The pre-credit sequence features a space capsule that swallows other space capsules, which is a quintessentially Dahl image. And the hollowed-out volcano that serves as the villain’s hidden base of operations is much more like something out of a Roald Dahl story than one of Fleming’s books. In fact the volcano base does not appear in the novel, and only came about after the Bond team spent three weeks in a helicopter flying around Japan in search of a great castle on a sea cliff, like the one Fleming had written about. When the Japanese government informed them that such castles did not exist (and had never existed), production designer Ken Adam hit upon the notion of utilizing the dormant volcanoes they had seen during their helicopter scouting trips.

There are numerous seemingly Dahlesque details to the movie. The pre-credit sequence features a space capsule that swallows other space capsules, which is a quintessentially Dahl image. And the hollowed-out volcano that serves as the villain’s hidden base of operations is much more like something out of a Roald Dahl story than one of Fleming’s books. In fact the volcano base does not appear in the novel, and only came about after the Bond team spent three weeks in a helicopter flying around Japan in search of a great castle on a sea cliff, like the one Fleming had written about. When the Japanese government informed them that such castles did not exist (and had never existed), production designer Ken Adam hit upon the notion of utilizing the dormant volcanoes they had seen during their helicopter scouting trips.

The volcano base—arguably the most iconic and grandiose gadget of the James Bond film series apart from the tricked out Aston-Martin—is one of Adam’s most impressive pieces of production design. It was far larger than anything ever constructed at England’s historic Pinewood Studios and it set the standard for secret lairs in countless adventure movies to come. The scale, function, and utter preposterousness of this set are delightful. Adam also designed a number of other eye-catching interiors for this picture, mixing his classically spare style with the Eastern aesthetics of the location.

To helm the project the producers approached Lewis Gilbert, the genteel director of Reach for the Sky, Sink the Bismarck! and the previous year’s surprise hit Alfie. Gilbert was reluctant to take on the now-enormous James Bond series and all of its accompanying expectations, but he liked the producers well enough to fly to Japan to help them scout locations and brainstorm ideas, and once there he was hooked. It was his suggestion to hire the masterful British cinematographer Freddie Young, who had shot Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Zhivago for David Lean, to make the picture more visually opulent. The result is the most sumptuous-looking James Bond film until Skyfall in 2012.

Peter Hunt, who had lobbied the producers for the job of directing the next Bond movie, was asked to direct the second unit, which he accepted, figuring it would be a step towards getting to direct a film of his own. In addition to overseeing many of the action sequences, Hunt was later brought in to re-edit the feature when the almost three-hour initial cut delivered by Gilbert’s regular editor Thelma Connell tested badly with audiences. Hunt saved the picture in post-production, as he had done in one way or another on all four prior Bond films, and he was indeed rewarded, as expected, with the job of directing the next Bond entry.

With a new director, a first-time screenwriter, and a weary, reluctant star, You Only Live Twice often feels labored and unsure of itself. The Japanese leads are uninspired, and the movie doesn’t heat up until the third act, where we finally go inside the volcano and see the face of super-villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Oddly, the actor originally cast in the role was Jan Wreich, whom Lewis Gilbert described as a “kindly old Father Christmas” and who was hardly convincing as the megalomaniac mastermind behind so many sinister plots. After several days of shooting, Gilbert convinced Broccoli that Wreich was not going to work as Blofeld, and he was quickly replaced with the English character actor Donald Pleasance, who had recently appeared in The Great Escape and Fantastic Voyage. Though other actors would portray Blofeld in subsequent films, Pleasance's characterization is definitive. When comedian Mike Myers developed the character of Dr. Evil for the satirical Austin Powers movies, the former Saturday Night Live star famously parodied Pleasance’s look. Indeed, You Only Live Twice serves as the basis for numerous scenes and jokes in those Austin Powers films, as well as for many other James Bond send-ups.