Whenever I am asked who my favorite filmmaker is I have to brace myself before I say Woody Allen. Especially in the last 20 years, there is a good chance this answer will elicit skepticism, dismissal, and even hostility. While it’s true that his more recent films have not come anywhere near the quality of his mid-60s through late-80s output, those “early funny ones” and even the early not-funny ones represent a body of work that is unrivaled in the history of cinema. Since he started making movies, Allen has written and directed virtually one picture a year for almost 50 years. That output alone would be an astonishing feat. The fact that most of the movies are good and many of them rank amongst my favorite films of all time is nothing short of miraculous.

You will find more films by Woody Allen on my list of favorites than by any other director. I have special affection for all but twelve of his over fifty movies. However, the two that will forever be my favorites are his classics from the late 1970s, Annie Hall and Manhattan. With these two pictures, Allen transitioned from a brilliantly funny writer, comedian, and novice film director into a great artist. In Annie Hall, working closely with co-writer Marshal Brickman and the great film editor Ralph Rosenblum, Allen developed a mastery of cinematic structure. In Manhattan, working closely with legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis, he developed his eye for composition and his faith in the power of the film frame. These pictures were followed by a decade of creative output in which he produced one amazing movie after another. In the 1990s, he would become more experimental and eventually less careful. By the Aughts he seemed to be sleepwalking through the process of making his films. But like the equally prolific Bob Dylan, Allen’s body of work is not diminished by the entries that lack the distinct spark of his greatest output—they just make it more interesting to explore.

ANNIE HALL

Annie Hall, revered by nearly all film lovers and one of only three romantic comedies to win an Oscar for Best Picture, was not the movie Allen set out to make. Originally titled Anhedonia, which is the inability to feel pleasure, the film was a semi-autobiographical exploration of the idiosyncrasies of Allen’s heart and mind, exploring his childhood, his life as a comic, and several of his failed romantic relationships. The story of his meeting, dating and breaking up with a woman named Annie Hall was just one of many subplots. This film is a great example of how a movie can become a masterpiece when it is treated as a living organism and allowed to grow and develop on its own terms, rather than being forced to adhere to the preconceived notions of its creator.

As Allen and co-writer Brickman have discussed in several interviews and biographies—and as editor Rosenblum so eloquently chronicled in his terrific book When the Shooting Stops—when the three men looked at their first cut of the film, they thought it was a disaster. It was full of great scenes that worked well on their own but not at all in conjunction with each other. The movie as a whole just didn’t play well. Their subsequent edit of the film not only condensed it (throwing out legendary scenes that most fans would kill to see but which were not saved), it refocused the narrative onto the love story between these two neurotic New Yorkers, making this film the quintessential romantic comedy of the “me” generation.

After his experience on Annie Hall, Allen began the practice of building into his small budgets a couple of weeks for reshoots after each film’s first assembly. This chance to revise was one of the primary reasons his movies from the 1980s were so effective. The best of his pictures were extensively reworked in post-production, as most films that are written and directed by the same person probably should be but aren’t. But for Allen, whose films principally take place in the same city with the same local actors and crew, reshoots are so relatively inexpensive that he’s one of the few filmmakers who can afford to take advantage of this process—though, unfortunately, I don't think he takes the time to do this anymore.

When Annie Hall was still Anhedonia, it was an absurdist film that ventured in and out of reality like a Monty Python picture. Though the film became more grounded when it became Annie Hall, it used even more non-traditional narrative devices to bridge the comedic set pieces and give structure to the film. Allen directly addresses the camera to set the story up—telling, not showing. He uses voice-over narration, breaks the fourth wall to comment on the action, and resorts to every imaginable gimmick to get laughs, including subtitles, split-screens, visualizations of what characters are thinking, and a total disregard for the reality of a given situation. Although I usually abhor the use of these overelaborate techniques in narrative features, in Annie Hall they all work for me. I’m not sure, but I suspect the reason I love the way Allen tells this story is because at the time the film was made these comedic gimmicks and narrative shorthand were not often used in commercial cinema—let alone done-to-death as they have been in so many film comedies of the last four decades.

Prior to Annie Hall, Allen’s output consisted of small but clever comedies and satires like Take the Money and Run, Bananas, Sleeper, and Love and Death. With this movie, Allen made a film about ideas and emotions and the attainment of perspective and wisdom—yet he was able to do it all without sacrificing the punchlines. In fact, Annie Hall was Allen’s funniest film to date and his most sophisticated work. Of course, as with most comedies, this is a film that should be seen in a packed theater. As funny as it plays at home, the film was made—and its rhythms timed—to be seen with a crowd.

Laughs aside, the real legacy of Annie Hall is that of a movie that perfectly captured a specific time and place—the 1970s in New York and LA—and showed the world that great romantic comedies, like all great romances, need not all end happily ever after. The final joke that Allen quotes at the end of the picture presents a universal truth: that love, sex, and interpersonal connections are not things we can pursue logically, but without them, life is greatly diminished.

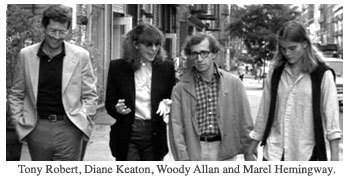

MANHATTAN

The success of Annie Hall enabled Allen to attempt his first serious film, Interiors, in which he emulated (some might say “satirized,” or, less charitably, “stole from”) Ingmar Bergman, his greatest cinematic hero.  Interiors was neither a box office success nor an artistic success, although I would argue that it is an extremely interesting failure and more successful than Bergman’s own attempt at an English language Bergman film, 1970s The Touch. (Good Lord, that’s a laughably bad picture!) With Interiors, Allen worked with the great cinematographer Gordon Willis, who had also shot Annie Hall as well as The Godfather I and II and All the Presidents Men. They focused on cinematic composition, color, mood, atmosphere, camera movement, and all the other things Allen had never bothered with when he was just trying to be funny. The result is a film that works brilliantly well on a visual level, despite its heavy-handed script.

Interiors was neither a box office success nor an artistic success, although I would argue that it is an extremely interesting failure and more successful than Bergman’s own attempt at an English language Bergman film, 1970s The Touch. (Good Lord, that’s a laughably bad picture!) With Interiors, Allen worked with the great cinematographer Gordon Willis, who had also shot Annie Hall as well as The Godfather I and II and All the Presidents Men. They focused on cinematic composition, color, mood, atmosphere, camera movement, and all the other things Allen had never bothered with when he was just trying to be funny. The result is a film that works brilliantly well on a visual level, despite its heavy-handed script.

The next film Allen and Willis (and Brickman) made was Manhattan. Shot in breathtaking black-and-white cinemascope, it is the final step in Allen’s evolution from a talented humorist to a full-fledged artist. With its look at the ways in which upper-class urban neurotics invent little problems for themselves in order to avoid confronting the larger existential issues they can't control, this film is utterly of (and about) its time.  But with its black-and-white film stock, Gershwin soundtrack, and use of New York City as a metaphor for all that is solid, permanent, and bigger than life, Manhattan is also a nostalgic film that celebrates an older, purer, simpler place and time. With its enduring themes of ambition and disillusionment, which resonate today more strongly than ever, it is truly a film for the ages.

But with its black-and-white film stock, Gershwin soundtrack, and use of New York City as a metaphor for all that is solid, permanent, and bigger than life, Manhattan is also a nostalgic film that celebrates an older, purer, simpler place and time. With its enduring themes of ambition and disillusionment, which resonate today more strongly than ever, it is truly a film for the ages.

Manhattan's devastatingly powerful final scene is the first fully pessimistic moment in the Allen canon. It’s not bittersweet like the end of Annie Hall but truly heartbreaking as Allen, through his character Isaac, acknowledges that to have a happy life, you do “have to have a little faith in people.” It’s clear that Isaac, and Allen, don’t have enough faith in people, or love, or in any belief system. What he does have faith in is the city, the music, and the movies. The fascinating question Allen asks… is that enough?

Manhattan is a self-critical film, and it is Allen's least favorite of his movies. When he finished it, he reportedly offered United Artists a deal wherein he would make his next film for free if they would not release Manhattan. Fortunately for us, that's not how things went. Interestingly, Allen’s most popular pictures are most often the ones he considers the least successful, because, I think, he sees in these movies his failure to achieve his original vision for them. I measure film not by how successfully it fulfills its creator's original intent but by how well it expresses what it ends up being about. Annie Hall is the case study for this measure, and Manhattan is the master class.