Amadeus was one of the first films to get me excited about the art of filmmaking. I was thirteen when the movie was released. By then, numerous pictures had long enthralled me with the idea of film as a medium, but this one caused me to take notice of the different aspects of film-craft: the writing, casting, cinematography, production, and costume design, and, most of all, the editing. Ironically, it was not until twenty years after it came out, when the so-called "Director's Cut" of the film appeared, that I became even more acutely aware of the preeminent significance of its editing. Amadeus epitomizes why the 1980s was my favorite decade of cinema, but it also exemplifies the more recent trend of revising and replacing great motion pictures of the past with inferior versions.

While little about this picture dates it in ways we now think of as a product of the '80s, it is difficult to imagine a film like it getting made the way this one was, and having the effect on mainstream culture this one did, during any other decade. Amadeus was an independent production with a studio-sized budget; a historical costume drama without a single trace of stuffy pretension; a biopic celebrated for taking wild creative license more than criticized for not studiously adhering to the known facts; a two-hour-and-forty-minute epic that breezes by like a tight, ninety-minute comedy; and a rare coming together of high-brow, award-winning filmmaking and easily accessible popular entertainment made for the widest possible audience. When it was released in 1984, everyone I knew—from my stuffy English teacher to my stoner bus driver—not only went to see it but saw it multiple times in the theater. Its popularity grew by word of mouth, opening strong but not reaching its peak box-office take until its eighth week in theaters. And while not all critics praised it unconditionally, it was one of the rare Best Picture Oscar winners that almost everyone at the time agreed deserved that award.

The film tells the life story of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart through the antagonistic remembrances of his fellow composer and conductor, Antonio Salieri. Mozart—arguably the most famous and revered classical music composer—died in 1791 at the young age of thirty-five. After his death, rumors grew that Salieri had poisoned him and that the two men had been bitter competitors. While little evidence of their rivalry exists, it makes for an intriguing story, especially when combined with the historical truth that Mozart himself did not complete his final composition—a requiem commissioned by an eccentric Austrian aristocrat. Mozart's “Requiem in D minor” is such a powerful, passionate, and virtuosic work that the stories perpetuated by his widow Constanze gained significant credence. According to these apocryphal accounts, Mozart believed he was writing the requiem for his own funeral, and he received the commission for it from a mysterious messenger who never revealed the identity of the man commissioning the piece. The speculation around the circumstances surrounding Mozart's death is a classic example of the old John Ford adage: when the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

Amadeus began its theatrical life in 1830 as a one-act play called Mozart and Salieri by Russian writer Alexander Pushkin. In 1897 an opera of the same name was composed using Pushkin's play for a libretto. Eighty years later, the acclaimed British playwright Peter Shaffer (Five Finger Exercise, The Royal Hunt of the Sun, Equus) used the story and the intriguing mysteries around Mozart's death to create his 1979 play Amadeus. Under the guidance of renowned English stage director Peter Hall, the play enjoyed successful runs in London's West End and on Broadway, eventually winning the Tony for best play in 1981. The Czech filmmaker Miloš Forman saw Amadeus early in its Broadway engagement. Forman, who was not looking forward to what he anticipated would be a rather heavy night of stuffy drama, was taken aback by the play’s humor. Shaffer was introduced to Forman that night during intermission and often told the story of Forman saying, "If the second half of this play is as good as the first, I will make a film of it!"

The inspired collaboration between Forman and Shaffer, two men of distinctive talent and ambition, resulted in the rare transformation of a solid but contained play into a magnificent and expansive film. Though many of his works had been made into features before, Shaffer himself had never written a screenplay until this time. While he takes sole credit for writing what the opening titles proclaim as, “Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus,” he was always eager to credit Forman as the person who taught him to write for the screen. This education transpired over the four months he lived with Forman at the Czech expat's house in Connecticut, working on the adaptation, as well as sharing meals, watching Family Feud on TV, and discussing the intricacies of reinventing a successful stage piece for a visual medium.

The narrative structure of the Amadeus screenplay is sublime—much more complex, nimble, and historically detailed than the play. Shaffer's theatrical framing device, an elderly Salieri speaking directly to the audience and inviting them to listen to the story of why he assassinated Mozart, transforms into a madhouse confession told to a young priest after the old, now forgotten composer attempts suicide. The film is able to dart back and forth, from the old Salieri telling his story to the events he describes, with the same agility that Mozart's compositions are woven in and out of the picture as both underscore and diegetic music. The various themes and motifs, theories and legends, period attributes and expository information, flow effortlessly around the central narrative of how the young Mozart, after a youth spent traveling around Europe with his father, performing for royalty and nobility, arrives in Vienna, meets the courtiers of the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II, marries, creates his most famous operas, and prematurely dies deeply in debt and unpopular. Though known primarily as a director, Miloš Forman was also a gifted screenwriter. His first two features, Loves of a Blonde (1965) and The Firemen's Ball (1967)—both nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar—are two of the most acclaimed works of the Czechoslovakian New Wave, which grew out of disgust with the communist regime that had taken over that country in the late ‘40s. Forman's first American film, Taking Off (1971), was a hit at that year's Cannes Film Festival, but got panned by American critics and tanked at the box office. Regardless of this commercial failure, Forman was hired to direct the screen version of Ken Kesey's seminal counterculture novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. That 1975 movie was a colossal success and the first film since It Happened One Night (1934) to sweep the Oscars in the five most prominent categories of Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor, and Best Actress. Cuckoo's Nest made Forman an A-list director, a reputation he maintained for the rest of his life, despite his uneven and less-than-prolific filmography. He followed Cuckoo's Nest with the musicals Hair (1979) and Ragtime (1981), but his adaptation of Shaffer's Amadeus would be his masterpiece.

Though known primarily as a director, Miloš Forman was also a gifted screenwriter. His first two features, Loves of a Blonde (1965) and The Firemen's Ball (1967)—both nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar—are two of the most acclaimed works of the Czechoslovakian New Wave, which grew out of disgust with the communist regime that had taken over that country in the late ‘40s. Forman's first American film, Taking Off (1971), was a hit at that year's Cannes Film Festival, but got panned by American critics and tanked at the box office. Regardless of this commercial failure, Forman was hired to direct the screen version of Ken Kesey's seminal counterculture novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. That 1975 movie was a colossal success and the first film since It Happened One Night (1934) to sweep the Oscars in the five most prominent categories of Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor, and Best Actress. Cuckoo's Nest made Forman an A-list director, a reputation he maintained for the rest of his life, despite his uneven and less-than-prolific filmography. He followed Cuckoo's Nest with the musicals Hair (1979) and Ragtime (1981), but his adaptation of Shaffer's Amadeus would be his masterpiece.

With no studios interested in financing a lengthy costume drama about rival classical composers, Forman and Shaffer teamed with one of Cuckoo's Nest’s main producers, Saul Zaentz, who took on Amadeus as an independent production. Zaentz, a gifted producer of prestige pictures, financed his fledgling production company with profits made from signing Credence Clearwater Revival to the Fantasy Records label in 1967 and his subsequent ownership of CCR's publishing rights. Zaentz put together approximately eighteen million dollars to make Amadeus—an astonishing amount for an independent film of that (or any) era. For the American distribution, he partnered with Orion Pictures, a company famous for not interfering in filmmakers' vision or creative process. Thus Forman was able to proceed with his movie—which, even after the Broadway success of the play, seemed a risky venture—secure that he would be able to deliver the film he set out to make.

Forman returned to his native Czechoslovakia to create the Vienna of Mozart's time because the capital city of Prague still contained so many buildings, public streets, and town squares that looked the same as they had during that period. He hired Italian, Czech, and German costumers, wig makers, and theatrical designers, all while deftly navigating the oppressive political regime that had banned him as a traitor when he left for the United States. Thus, the recreation of the era feels authentic and natural, with no scene looking at all like it was shot on a movie set.

When it came to casting, Forman's choice to populate Amadeus predominantly with American actors was far more bold and controversial. By this point, moviegoers of all nations were used to seeing British actors in prestige period pictures, regardless of the country in which the story was set in. Amadeus takes place in Vienna, Austria, during the latter half of the eighteenth century, and even though most of the characters would have spoken German, contemporary audiences would have thought nothing of seeing English actors speaking English dialogue with English accents, as was the case in all of the prior stage productions.  Indeed Forman and Zaentz seriously considered casting Kenneth Branagh, the twenty-four-year-old wunderkind of the London theater, as their Mozart. But after more than a year of casting sessions on two continents, they had decided to go with the American stage actors F. Murray Abraham as Salieri and Jeffrey Jones as Emperor Joseph II (Jones bore a stunning resemblance to portraits of the actual Emperor). With these men in place, the surprising winner of the title role was Tom Hulce, best known for his role as “Pinto” in National Lampoon's Animal House (1978). Hulce proved to be an inspired choice. From his first moment on screen, in a scene expanded from the character's introduction in the play, Hulce's performance as the Wolfgang Mozart imagined by Shaffer is so different from what audiences expect that it shocks us. The Mozart envisioned in Amadeus is a vulgar, immature buffoon who just happens to also be a musical genius. It is this dichotomy more than anything else that stokes Salieri's hatred and drives the narrative and the principal themes of both the play and the film. The contrast between the two characters in the movie is made all the more sharp by the unmistakable differences in Abraham's controlled, ambitious, darkly dignified performance and the loose, unpredictable, seemingly carefree Hulce, who also gifts Mozart with the ludicrously goofy laugh that became one of the movie's iconic signatures.

Indeed Forman and Zaentz seriously considered casting Kenneth Branagh, the twenty-four-year-old wunderkind of the London theater, as their Mozart. But after more than a year of casting sessions on two continents, they had decided to go with the American stage actors F. Murray Abraham as Salieri and Jeffrey Jones as Emperor Joseph II (Jones bore a stunning resemblance to portraits of the actual Emperor). With these men in place, the surprising winner of the title role was Tom Hulce, best known for his role as “Pinto” in National Lampoon's Animal House (1978). Hulce proved to be an inspired choice. From his first moment on screen, in a scene expanded from the character's introduction in the play, Hulce's performance as the Wolfgang Mozart imagined by Shaffer is so different from what audiences expect that it shocks us. The Mozart envisioned in Amadeus is a vulgar, immature buffoon who just happens to also be a musical genius. It is this dichotomy more than anything else that stokes Salieri's hatred and drives the narrative and the principal themes of both the play and the film. The contrast between the two characters in the movie is made all the more sharp by the unmistakable differences in Abraham's controlled, ambitious, darkly dignified performance and the loose, unpredictable, seemingly carefree Hulce, who also gifts Mozart with the ludicrously goofy laugh that became one of the movie's iconic signatures.

While there are plenty of Brits in supporting roles—most significantly Simon Callow, who played Mozart in the original London stage production—they often adopt American accents. Indeed Callow, playing the grandiloquent German actor and down-market theatrical impresario Emanuel Schikaneder in the movie, based his speech patterns and performance style on American actor and theater legend Orson Welles. Key supporting players like Vincent Schiavelli, Christine Ebersole, and Cynthia Nixon also bring an unmistakably American twang to the picture.  Meg Tilly, who caught the eye of many audiences and critics in the previous year’s Psycho II and The Big Chill, was cast as Mozart's wife Constanze, but she had to drop out the day before shooting started due to an injury. Elizabeth Berridge, the star of Tobe Hooper's slasher film The Funhouse (1981) was quickly brought in to replace her. Berridge's performance is one aspect of Amadeus that critics often point out as a weak link. Especially after Tilly went on to her Oscar-nominated role in Agnes of God the following year, many wondered how much better Amadeus might have been with the gifted Meg Tilly in this key role. But I think Berridge makes an ideal partner for Hulce. She seems far more like the simple, saucy, supportive girl this Mozart would fall for, and someone who would stay in love with him despite everything he puts her through in this story. It's easy to see why Mozart's father would instantly disapprove of her so harshly, a key aspect of the narrative. And she conveys a crucial naiveté that would be less intrinsic with Tilly. Berridge also projects the same unmistakable Americaness that drives home how out of place the Mozarts are in the sophisticated milieu of the picture.

Meg Tilly, who caught the eye of many audiences and critics in the previous year’s Psycho II and The Big Chill, was cast as Mozart's wife Constanze, but she had to drop out the day before shooting started due to an injury. Elizabeth Berridge, the star of Tobe Hooper's slasher film The Funhouse (1981) was quickly brought in to replace her. Berridge's performance is one aspect of Amadeus that critics often point out as a weak link. Especially after Tilly went on to her Oscar-nominated role in Agnes of God the following year, many wondered how much better Amadeus might have been with the gifted Meg Tilly in this key role. But I think Berridge makes an ideal partner for Hulce. She seems far more like the simple, saucy, supportive girl this Mozart would fall for, and someone who would stay in love with him despite everything he puts her through in this story. It's easy to see why Mozart's father would instantly disapprove of her so harshly, a key aspect of the narrative. And she conveys a crucial naiveté that would be less intrinsic with Tilly. Berridge also projects the same unmistakable Americaness that drives home how out of place the Mozarts are in the sophisticated milieu of the picture.

The unusual and unsettling quality of so many American actors in such a European setting telling such a European story helps to upturn the expectations of first-time viewers as they settle in to watch a biographical period piece about classical music composers in eighteenth-century Vienna who routinely watch four-hour operas while wearing powdered wigs and silk stockings. The playful casting and ribald tone of the movie helped make it a hit with suburban audiences and captured the polarity that fascinated Shaffer about Mozart in the first place. When the author embarked on his play, he read through the many letters Mozart wrote over the course of his life in Vienna. Shafer describes these correspondences as like “something written by an eight-year-old. At breakfast he'd be writing this puerile, foul-mouthed stuff to his cousin; by evening, he'd be completing a masterpiece while chatting to his wife.” Shaffer's depiction of Mozart's crassness, delight in scatological humor, and narcissistic insensitivity to other people's feelings helps the author drive home intriguing themes concerning the mystery of genius and the inability of ordinary humans to comprehend extraordinary ones.

While the play concerns itself primarily with Salieri's feud with God over the Divine's unfair distribution of talent, the film uses that conceit to ground and dramatize a fictionalized biography and character study of Mozart. Despite the drawing-room nature of many of its scenes, the film of Amadeus plays out on such a broad and vibrant canvas and is so cinematically visual and full of energy it's hard to believe, if you've never seen the stage version, that it’s based on a play. The cinematography by Forman's frequent collaborator Miroslav Ondříček (who shot the director's early Czech films and his American musicals as well as Lindsay Anderson's If… and O Lucky Man!, George Roy Hill's The World According to Garp, and Mike Nichols' Silkwood) is a sumptuous feast for the eyes. The movie was shot on location in meticulously preserved palaces, churches, museums, apartments, and theaters—including the very opera house where Mozart's Don Giovanni and La clemenza di Tito premiered. That venue, the last wooden opera house left in the world, looked almost exactly as it had two centuries earlier, and Forman was able to place Tom Hulce in the very spot where the real Mozart conducted. The electrical lights were replaced with replicas of the hand-lit chandeliers, rigged with special triple-wick candles that would burn bright enough to photograph the scenes with minimal additional lighting.

But what truly makes Amadeus a superior film is the editing—specifically the ways in which Mozart's music is utilized. More than any other improvement from the stage version to the film is that the original play contains less than nine minutes of music, whereas the movie reverberates with some of the greatest music ever created. Over 100 of the film's 161 minutes feature the score conducted by Sir Neville Marriner and performed by his celebrated Academy of St Martin in the Fields orchestra. As the various beats of the story unfold, we witness Mozart and Salieri conducting their music, playing their music, composing their music, and hearing it as they read it or write it on the page. We see their operas being staged, and the music is edited in such a way that we come to understand how some of the compositions came about (at least as Shaffer fancifully envisions it). Cues from Mozart's Requiem send chills down the spine when they suddenly appear on the soundtrack at key moments. While other inventive uses of music engender smiles and even outright laughter, like the depiction of how Mozart gets the inspiration for his iconic Queen of the Night aria in The Magic Flute, or the ecstatic way he conducts the star of The Abduction from the Seraglio, where we suddenly understand why Mozart's palpable connection with the diva specifically enrages Saliari.

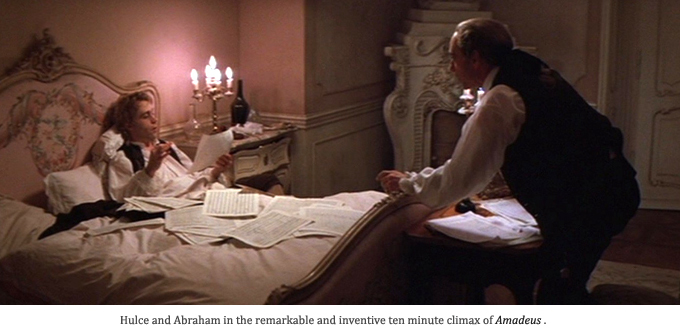

The magnificent use of music culminates in a long fictional scene in which Mozart, on his deathbed, dictates his final composition to Salieri. It's a climax unlike anything seen before in film or on stage—depending on sound rather than spoken dialogue, action, or visuals to convey its meaning. As the two characters discuss what the various instruments and singers will do at each bar of music, we hear what they're describing on the soundtrack. Both men can clearly hear the same music in their heads, but only one of them is capable of creating it.

The film's narrative pacing and the masterful way everything is held together and moved along by the music are the main reasons why this lengthy movie can be enjoyed over and over again, the way a beloved comedy or animated children's fantasy often can. The deft hands of Forman, Shaffer, and editors Nena Danevic and Michael Chandler bring an enchanting lightness to what, on the surface, is a dark and often grim story about a spiteful man's murderous jealousy and the tragic downfall of one of the greatest artistic geniuses in history. Watching Amadeus repeatedly as a kid was one of the gateways to my passion for film editing. Getting sucked in by the power of the dialogue-free scenes—especially those of Mozart conducting his operas—was far more thrilling than any action sequence I had seen to date. I was stunned that the specific order of shots cut in rhythm to this incredible music could have such a visceral and exhilarating effect on me. It became a favorite movie long before I started to seriously study film, and it has always remained high on my 100 favorite films list.

Unfortunately, Amadeus is one of those movies that, despite being a Best Picture winner and one of the most well-remembered films of its decade, is no longer easy to find in its original version. Forman and Zaentz's first fine cut came in at three hours and was given an “R” rating by the Motion Picture Association of America. As Forman would recount decades later, he worried that a three-hour running time might be too much for a mainstream audience that was already being asked to watch a historical period picture about classical music with no movie stars. Zaentz had his investment money to protect and Forman had his reputation to consider, so twenty minutes were removed, including a scene of nudity. The result was a shorter theatrical version with a “PG” rating.

Yet these cuts were neither compromises nor cynical concessions made strictly to improve the bottom line. They were the essential final creative decisions made by the filmmakers. No maximum running time or requirement for a family-friendly MPAA rating was imposed on Forman, who was working outside the purview of a studio and had final cut on the picture. The 160-minute version Forman and his team arrived at in 1984 was the definitive version. It is the film that won the hearts of audiences and critics, and the film that became a part of cinema history, winning eight Oscars, four BAFTAs, four Golden Globes, a César, and numerous other major awards. Still, in 2002, Forman decided to revert back to his three-hour fine cut, and Warner Brothers, which by then owned the rights, reissued that edition as Amadeus: The Director's Cut.

"Director's Cut" is an elusive and problematic term. Its most basic definition is the penultimate version of a movie a director and editor complete and submit to a studio, assuming there is a studio financing and releasing the picture. In such cases, the studio, which has the power to determine the final cut, gives notes on the director’s cut, previews that version with test audiences, and determines how to possibly “improve” the movie. There are many well-documented cases when studios have ruined a filmmaker’s work by re-cutting it out of stupidity, lack of understanding and creative ability, or fears that the movies will not do well financially. These examples are responsible for the second definition of Director's Cut: the latter-day reconstruction of a feature (either by the director, a studio, or a distribution entity that years later gains control of both the rights to a movie and the original negative and other source materials used to create it) into a new version that more closely adheres to the presumed intention of the director. Sam Peckinpah's Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973)—another one of my 100 favorite films—is the best example I know of where the “director’s cut,” is the best and most definitive version of a film, even though it is not actually Peckinpah's final cut, but merely an approximation of what the director and his editors would have wanted to deliver had they been allowed to finish their film properly.

Frequently, “director’s cut” is no more than a misleading marketing term used by a studio that wants to generate press and renewed interest in a movie they plan to reissue by making changes, with little to no input from the original filmmaker, such as the 1992 release of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, The Director's Cut. But the definition that is now the most prevalent is the revisionist form of “directors cut,” which is a contemporary re-edit by directors who return decades later to films they regard as flawed or out of step with various modern standards, and reconstruct them into something they feel better about. Charlie Chaplin's 1940's re-release of his 1925 silent masterpiece The Gold Rush is probably the first instance of this practice. A more recent example is the 2012 digital restoration of Michael Cimino's infamous 1980 studio-bankrupting western epic, Heaven's Gate. Purveyors of the auteur theory of filmmaking would have us believe that it is the right of the director, as the artist primarily responsible for all aspects of collaborative creative work, to make revisions to his or her final product whenever they wish. But these updated versions often destroy that director's work—to say nothing of the artistic efforts of countless craftsmen intimately involved in bringing a great picture to the screen.

The three-hour cut of Amadeus falls mostly into the first category of director's cut, in that it was the first fine cut Forman completed with his editors and creative team. But, since it is the only version to be digitally transferred to high-definition video for BluRay, streaming, and theatrical reissue, it has become the de facto definitive version of the picture. Only those of us lucky enough to have access to an original 35mm release print can view this movie under ideal circumstances as it was meant to be seen by all the artists involved, including the director.

After Amadeus: The Director's Cut was issued, Forman gave countless interviews about how this early cut was always his preferred version and that it best represented his vision of the film. But for many years after the triumphant success of Amadeus in 1984, both he and Shaffer gave numerous interviews and participated in making-of documentaries about the film in which they discussed all the creative reasons why they removed certain scenes and sequences in the final cutting of their movie. With great pride, they pontificated on how much they loved certain scenes but had to take them out for the good of the picture. For example, there are two scenes in which Mozart visits a wealthy man (played by Kenneth McMillan) for the purpose of instructing his daughter in piano. In the first scene, the man insults Mozart by showing more interest in his distractingly loud dogs than in the great artist’s skills at the piano, so Mozart storms out. It's a good scene and an example of the deeper examination in the longer version of how Saliari schemes to humiliate and discredit Mozart. But its main function is to set up a later scene in which the now sick and destitute Mozart returns to the man’s home to ask again for employment and, when none is forthcoming, to beg for money. Forman believed this scene featured Tom Hulce's best work in the picture, and it pained him to cut it. But cut it he did, because he knew the overall film played better without this extraneous plotline.

The most significant change comes earlier in the picture when Constanze, angry with her husband that he will not submit examples of his work to obtain a royal teaching position, visits Salieri and asks for his help. In both versions, Salieri looks at Mozart's work and is astonished to discover that his rival’s first drafts look like completed compositions, with no corrections of any kind, as if Mozart just wrote out fully finished music like he was taking dictation from God. As Salieri flips from piece to piece, we hear snatches of Mozart's melodies playing inside Salieri's mind as he reads the notes on the pages. He grows angrier and angrier as he comes to realize the full extent of how superior a composer Mozart is to him. He throws the sheet music on the floor, leaves the room in disgust, and removes the crucifix from his wall, burning it in a fireplace. He swears that from now on, he and God are enemies because God chooses for his Earthly instrument a boastful, smutty, infantile boy like Mozart and grants Salieri only the ability to recognize the incarnation.

This sequence features some of the best moments in Amadeus. But in the longer version, it's augmented by Salieri's demand for quid pro quo. He claims he will help Mozart only if Constanze has sex with him. At first, she refuses, but later, she returns to Salieri with every intention of sleeping with him. Salieri, who long ago swore an oath of chastity if God would bestow musical talent upon him, is humiliated when he sees Constanze disrobing. Paralyzed, he orders her out.  It's easy to understand how a scene like this would come about during the writing process. It's a dramatic, if not especially innovative, conceit for the villain to force the protagonist's wife into compromising her virtue to help ensure her and her husband's future. And the surprise of Salieri's reaction to seeing her naked flesh is effective. But, as Forman and Shaffer discovered in editing, the scene in which Saliari reads Mozart's sheet music is so powerful, such a cinematic and thematically relevant depiction of Saliari's humiliation, that the following scene in which Constanze submits to him could never top or even equal it. Therefore, the later scene became redundant and was rightly removed.

It's easy to understand how a scene like this would come about during the writing process. It's a dramatic, if not especially innovative, conceit for the villain to force the protagonist's wife into compromising her virtue to help ensure her and her husband's future. And the surprise of Salieri's reaction to seeing her naked flesh is effective. But, as Forman and Shaffer discovered in editing, the scene in which Saliari reads Mozart's sheet music is so powerful, such a cinematic and thematically relevant depiction of Saliari's humiliation, that the following scene in which Constanze submits to him could never top or even equal it. Therefore, the later scene became redundant and was rightly removed.

Whether or not the real Mozart was able to write perfectly rendered final compositions in first draft form is a subject debated by music scholars, but no filmmaker has ever possessed this ability. Movies are constantly revised from the page to the shooting to the editing. This ever-evolving process dictates requirements to a director as much as the inverse. When writing the script, Shaffer and Forman could envision the way the scene of Saliari reading Mozart's sheet music would play, but they could not know exactly how potent and effective it would be until they shot, recorded, and put it all together in the editing room. In collaboration with Neville Marriner, they devised which snatches of music would be heard as Saliari flips through Mozart's written works; the melodies he hears shifting abruptly as the astonished maestro glances from one piece to another. The moment is a brilliant cinematic conceit, but only when placed into the body of the film does the clarity of its expository and emotional impact declare itself. The scene is special in part because of the thrilling quality of the music, the cutting, and Abraham's performance, but also because it is a scene unlike any other found in any movie before—unlike the convectional trope of Saliari demanding sex from Constanze.

During that amazing scene, as Saliari reads Mozart's sheet music, we hear the bitter old man’s narration about what it was like for him to see Mozart's handwritten work: “Displace one note and there would be diminishment. Displace one phrase, and the structure would fall.” Yet twenty years after completing his greatest work of art, Miloš Forman seemed to ignore those words. He returned to his penultimate version, one which restored scenes he'd always enjoyed but discarded the hard work he had put into making his film as perfect as it could be in the critical final months of its gestation. Amadeus: The Director's Cut is not a terrible movie that drags or confuses or infuriates the viewer, but it is a diminished work with a less sublime structure and pace. It is not the thrilling epic drama that flies by like a ninety-minute comedy and makes you want to watch it all over again as soon as it ends. And it is not the refined feature the world fell in love with when it hit theaters in 1984. I have no beef with alternative editions of films existing as supplements to their official theatrical versions, but I consider it a cinematic sin when those revised editions replace the primary versions that a team of filmmakers collectively worked on, scrutinized, tested, and intentionally launched into the world.

The way we view, discuss, and consume movies has changed dramatically since the 1980s. It is common now for any popular film (and even some that bomb) to exist in multiple formats. This variety of formats and versions should make for more choices, not fewer. Celluloid and digital, standard and IMAX, 2D and 3D, and even color and black & white editions of the same movie are released simultaneously, to say nothing of the multitude of ways in which we view films today. So, the very idea of a definitive version of a film is more elusive now. Yet in cases like this one, the only easily accessible option is the inferior "Director's Cut." It's still an excellent film, to be sure, but a mediocrity when compared to the genius of the original. Now that all the principal creative authors of Amadeus are dead, I fear the collective memory of this wonderful movie will grow fainter, all the time fainter, until no one sees it at all.