Most historical epics, especially those made during the Golden Age of Hollywood, are impressive, grandiose, long, expensive, and, more often then not, dull and dated. They're prestige pictures that studios and filmmakers purport to create for the edification of their audiences, although invariably the greatest benefit accrues to the creators' own reputations and market shares. All too often these films amount to little more than overstuffed melodramas presented on a large, sprawling canvas, that people go see out of a sense of obligation rather than excitement.

One problem with historical epics is that their subjects are frequently more high-minded than dramatic interesting. The characters in these movies tend to be “people so lofty they sound as if they shit marble,” as Mozart complains in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus when he's commissioned to compose operas about old, dead legends. It doesn’t help that many major stars have been badly miscast in these films, especially during the ‘50s and ‘60s. For every perfect pairing of actor to historical figure, such as Charles Laughton as Henry VIII, George C. Scott as General George Patton, or Daniel Day-Lewis as Abraham Lincoln, there are dozens of horrendous casting decisions, like the aging James Stewart as young Charles Lindbergh, John Wayne as a ludicrously implausible Genghis Khan, and Charlton Heston in pretty much every historical role he ever took.

But an even bigger issue than bad casting was the new film formats that the studios developed for use in these pictures. In the silent-movie era, biblical epics brought audiences to the cinemas by the thousands. After the transition to sound, films like C.B. DeMille’s Sign of the Cross reveled in nudity and lascivious (even perverted) sexual content under the guise of presenting a morally instructive narrative. But by the 1950s, long after censorship put an end to this practice and television was threatening the very existence of the movies, film studios had to devise new ways to lure audiences back to theaters. The studio heads wanted movies to be infinitely grander, sharper, more vibrant and more exciting than anything that could be found on TV. And what better content to use as fodder for these gargantuan pictures than the great figures and events of world history? Films so ambitious demanded sweeping, breathtaking images, so the movie studios invented large-format photography processes to generate magnificent footage. Thus began the era of specialty processes like 70mm, VistaVision, 3D, Cinerama, and various anamorphic and non-anamorphic widescreen formats.

But the very technologies that made many of these films so visually distinctive also made them stiff and clunky because the exciting new formats inhibited the storytelling as much or more than they enhanced it. The cumbersome, specialized equipment these processes demanded acted like a creative straitjacket for the directors, actors and technicians who made the films. For example, the size and weight of 70mm equipment necessitated limited camera movement, and the larger negatives produced a narrow depth of field that made it exceedingly difficult to keep in focus actors who were not stationary. The Cinerama process required synchronizing multiple cameras and the accompanying racket made by the trio of film rolls cranking away inside the housing hindered dialogue recording. Narrative films shot in Cinerama have a distinctive rigidity because the extremely wide focal length of the lenses necessitated awkward staging of actors within the frame in order to maintain their eye-lines. Directors of many early widescreen 35mm films were limited to the one fixed anamorphic lens that was available for their specific camera rather than the wealth of conventional lenses available for shooting in the standard process.

When these movies eventually made their way to television and home video, everything that was impressive and powerful about them was lost on the small screen, leaving only the problematic and embarrassing aspects. This tarnished the reputations of many of the best pictures from the genre's heyday, and the films themselves were nearly allowed to rot away into oblivion, as many of the new formats had a far shorter shelf life than conventional 35mm film stock. The rich color images quickly began to fade, and the negatives themselves began to shrink and turn to vinegar after only a few years.

Lawrence of Arabia is the film that most successfully conquered the challenges of epic film production, withstood the critical attacks on the genre, and led the charge of restoration that became the film-preservation movement. The film tells the largely true story of T.E. Lawrence, a repressed British mapmaker enlisted in the army during World War I who rose to become a guerrilla leader of Arab tribesmen fighting against the powerful Turks. I consider Lawrence to be the greatest of all historical epics, and I also think it uses the medium of cinema in ways as remarkably innovative as Birth of a Nation, Citizen Kane or 2001, A Space Odyssey. Like those groundbreaking films, it fully inhabits the giant cinema screen and uses it in ways never thought of before, all the while never losing the dramatic thread of its fascinating story. I’ve seen Lawrence in more formats than any other picture, including 70mm, 35mm, 16mm, VHS, Laserdisc, DVD, BluRay and the recent 8K digital restoration, and I can attest that the film's story holds up in even the weakest presentation. But a viewer can only fully experience this picture by seeing it projected in the highest possible resolution onto the largest possible screen. The visuals in Lawrence of Arabia aren't mere showcases for spectacle, elaborate compositions and strikingly presented locations. Director David Lean utilizes his vast landscapes, rich palette of colors, and ability to juxtapose the relative sizes of people and objects within his gigantic 70mm frame, to convey story points and to emphasize thematic ideas.

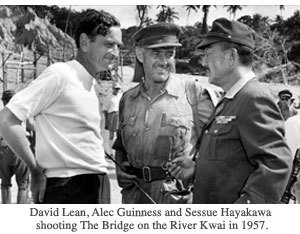

Lean began his career as an editor during the early sound period. By the time Noel Coward selected him to co-direct the prestigious In Which We Serve (another of my hundred favorite films), he had a better working knowledge of how to put a movie together and what makes a great film than most veteran directors. After directing eleven acclaimed but modest British pictures, he teamed up with the ambitious independent producer Sam Spiegel to make The Bridge on the River Kwai. That film won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and although it's a fictional film about WW II, Kwai bears many of the virtues and faults of a historical epic. Having proved their aptitude for the genre, Lean and Spiegel received a colossal budget for Lawrence, their next project, and they also brought to bear the tremendous amount of experience they amassed during their previous collaboration.

Lean entered the production of Lawrence with a clear vision of the unprecedented feats he wanted to accomplish on the big screen, and he had the bankroll to execute those ideas unstintingly and without compromise. The film's most iconic images depict camel-riding figures dwarfed by expanses of virgin sand, emphasizing the preeminence of the natural world over the individual human beings who spend such short amounts of time in it. Lean conveys the sun’s unbearable heat and the desert’s immeasurable distances by lingering at great length on his compositions. Not only does he use the 70mm frame’s unparalleled ability for capturing majestic vistas to convey Lawrence’s feelings of wonder, power and belonging, Lean also puts the format’s lack of agility to his advantage, conveying Lawrence’s feelings of repression, bondage, and devastation. In so many epic films, we're painfully aware of the constraints placed on the filmmaker in telling the story. Here, though, we're completely immersed in the experiences of the characters, whether it's the claustrophobia of Lawrence's first military station, a “nasty, dark little room,” or the feeling of invincibility he discovers when the desert winds ripple through his flowing white Arab robes, or the chaos and confusion of the first Arab National Council he helps bring about.

The 70mm format has such vivid clarity and unforgiving resolution that even the slightest disturbance of sand would register on film, and the latitude of exposure makes the lighting continuity from shot to shot all the more critical. Normally these issues would make it extremely difficult to film multiple takes of sequences in which actors ride across pristine sand dunes or scenes that feature compositional interplay between the characters and the sun, the clouds or the stars. But Lean and cinematographer Frederick Young had the rarified privilege of simply waiting for nature to reset their stages for them. They could stop shooting for days until the celestial elements were in just the right position to achieve a desired shot, or for the wind to blow away any traces of a previous take.

The most famous example of Lean’s mastery of the 70mm format is the first appearance of actor Omar Sharif. Lawrence and his desert guide, Tafas, have drunk from a well that belongs to Sherif Ali (played by Sharif), and when they realize that they have been discovered, they have no choice but to wait for him to ride up to them and administer punishment. Lean holds silently on the static images of the two men standing by the well while its owner approaches. Ali begins as a tiny dot in the frame, barely visible even on the largest of screens. As he gets closer, it becomes clear that he's a man of high status and deadly power. On a small display, the sequence seems absurdly long and flat, but on a giant theater screen it brims with suspense and mystery. It also conveys the immense scale of the deserts that Lawrence will eventually have to cross, and we sense the strange power of this environment to mold men in ways unfathomable to most Westerners.

Visual poetry aside, Lawrence is also atypical of most historical epics because it is an enigmatic character study rather than a pumped-up, dumbed-down presentation of a historical figure. It's ostensibly a war movie, but it features few scenes of battle and minimal violence. In fact, the four-hour picture contains very little action of any kind, and virtually no melodrama. There's also no trace of a love story, an element commonly woven into historical narratives to make them more relatable to female audiences. Quite the contrary, this movie has no female characters at all. Apart from quick glimpses of a harem and the sounds of a burqa-shrouded gathering whose ululations echo through the mountains as Lawrence’s army passes them by, the only woman involved in the film is its brilliant editor Anne V. Coats. Coats introduced Lean to the French New Wave which inspired them to create many of the most memorable elliptical cuts from scene to scene in Lawrence--most notably the early cut from O'Toole blowing out the match to the sun rising in the desert. The amazing visuals are usually get the lion's share of the prize when Lawrence is written about or discussed, but I would argue that the editing, though subtler, is even more impressive. (Anne V. Coats is a fascinating character in her own right, with a career that spans half a century and continues to this day. She has worked with directors as diverse as Ronald Neame, Richard Attenborough, Sidney Lumet, Miloš Forman, David Lynch, Frank Oz and Steven Soderbergh on some of their most acclaimed films, and her collaboration with the great editor-turned-director Lean on this picture was significant.)

Lawrence creates an oddly insular world populated entirely by men and boys, which makes it even more homoerotic than historical epics like Ben Hur and Spartacus that blatantly hint at their characters' bisexual exploits. Most historians agree that the real T.E. Lawrence was gay, but the film does not make this a focal point of the narrative (which would have been impossible anyway due to '60s-era censorship). Instead, Lean and screenwriter Robert Bolt give their Lawrence a distinctive “otherness” that is not merely sexual. There's a strange undercurrent to the character's mercurial personality that's difficult to pin down but fascinating to contemplate. Is he a sensualist who gets turned on by denying himself the most basic of human comforts and necessities? Is he a masochist who discovers that he's actually a sadist? Is he a man with a God complex who claims to be just an ordinary soldier? Is he an unstable person who himself isn't sure if he's blessed with extraordinary powers or simply verging on insanity? In an almost surreal moment near the end of the first half, when Lawrence and his young servant finally reach the Suez Canal after crossing the Sinai Desert, a British motorcycle rider (voiced by Lean) shouts out, "Who are you?" over and over, but Lawrence does not answer. This is the central question of the film. We are never truly clear what drives T.E. Lawrence, which is the main reason we want to revisit this lengthy movie again and again.

Even decades after its release, Lawrence barely feels dated, and I attribute this timelessness more than anything to Peter O'Toole. When he was cast in the lead role, O’Toole was an young stage actor with striking good looks and an androgynous, slightly awkward quality, perfect for this very different kind of action hero. O’Toole’s screen presence is at once robust and frail, contained and explosive. He is ingratiatingly charming but madly obsessive. O’Toole carries the colossal picture with grace, subtlety, and power, which is especially impressive since this was his cinematic debut. The actor’s clumsy movements and odd speaking voice brought the enigmatic character to life in exactly the way Lean and Bolt wanted: Lawrence's peculiarities cause nearly everyone in the film to underestimate him at first, but his strange self-confidence gives him an authority radically different from that of conventional military men, and his singular presence, which verges on the divine, inspires the various Arab tribes to unite and follow him on missions that would otherwise seem suicidal.

Lean and Spiegel threw a wide net when it came to casting their Arab characters. For the critical role of Sherif Ali, Lawrence’s fiercely loyal comrade, the filmmakers auditioned well-known French, German and even Indian character actors before realizing that they already had within their midst an Arab movie star with the looks and talent to become an international sensation. Omar Sharif had originally been hired for the minor role of the guide who first takes Lawrence into the desert. At the time, Sharif was an unknown outside of the Middle East but a hugely popular romantic leading man in his home country of Egypt. And after the French star Alain Delon turned down the chance to play Ali right before the start of production, Sharif stepped into the role that launched his impressive Hollywood career. The distinctly Middle Eastern matinee idol already had impeccable acting chops and a melodious command of the English language. Arguably, the actor's dark complexion and chiseled features made him even more impossibly handsome than O’Toole, and the dynamic between the two unusual young stars is one of the film’s greatest pleasures.

Sharif also lent Lawrence an additional layer of authenticity that many films in the genre lack. Casting white actors in heavy make-up to play non-white historical figures was commonplace in the 1960s, and the practice badly dates many films of the genre, with a similarity to blackface that can be uncomfortable for contemporary viewers to watch. Even Lawrence isn't wholly innocent of this; its top-billed stars are Alec Guinness, who plays the Arab Prince Faisal, and Anthony Quinn, who places the Bedouin shaikh Auda abu Tayi.  Quinn, a Mexican actor who played characters of virtually every ethnicity over his long career, does not raise too many objections even today, and there's a striking resemblance between him and photographs of the actual Auda abu Tayi. It's a little harder to overlook Guinness’s deep green eyes and his signature soft-spoken English lilt, but Guinness nevertheless does the picture infinitely more good then harm. From a practical standpoint, his participation was vital to getting the movie made: after winning the best actor Oscar for Bridge on the River Kwai, his previous collaboration with Lean, Guinness was the only cast member (other than Quinn) who could qualify as bonafide, contemporary movie star and a guarantee of some of box office returns for the immensely expensive project. But even from an artistic standpoint, Guinness's Cheshire Cat-like performance perfectly suits the script’s depiction of Faisal as a consummately pragmatic politician; even more of an upper-class sophisticate then the British officers he deals with.

Quinn, a Mexican actor who played characters of virtually every ethnicity over his long career, does not raise too many objections even today, and there's a striking resemblance between him and photographs of the actual Auda abu Tayi. It's a little harder to overlook Guinness’s deep green eyes and his signature soft-spoken English lilt, but Guinness nevertheless does the picture infinitely more good then harm. From a practical standpoint, his participation was vital to getting the movie made: after winning the best actor Oscar for Bridge on the River Kwai, his previous collaboration with Lean, Guinness was the only cast member (other than Quinn) who could qualify as bonafide, contemporary movie star and a guarantee of some of box office returns for the immensely expensive project. But even from an artistic standpoint, Guinness's Cheshire Cat-like performance perfectly suits the script’s depiction of Faisal as a consummately pragmatic politician; even more of an upper-class sophisticate then the British officers he deals with.

Rounding out the cast as Lawrence’s military superiors are Jack Hawkins, Anthony Quayle, and the always-welcome Claude Rains. Each actor brings depth and subtlety to his small role, but, more importantly, the three men create a context for O’Toole’s portrayal of Lawrence, which is in such contrast to their easily comprehensible personas. None of the film's characters can truly grasp what drives its strange central figure, and the audience becomes more and more fascinated as we see him through the different perspectives of the more understandable individuals.

The film created a template that countless epics, including Dances With Wolves, The Last Samurai, and Avatar, would follow: a white man rejects societal norms by going native and then rises to become the leader and eventual savior of an indigenous culture. But what sets Lawerence apart from its successors is that it simultaneously celebrates and criticizes the exploits it chronicles. Thirty years before the W. W. Beauchamp character in Clint Eastwood and David Webb People’s Unforgiven forever changed the way we view the heroes of the American Western, Lean and Bolt gave us Jackson Bentley (played by Arthur Kennedy) in Lawrence. Bentley is an American journalist who romanticizes and plays up the myth of Lawrence for his Western readers. Lawrence seems as much based on the writings of Lowell Thomas (the inspiration for the Bently character) as on T.E. Lawrence’s own book Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Many have called the film factually inaccurate, but the filmmakers' approach of printing the legend while simultaneously questioning it renders Lawrence virtually immune to this type of criticism. In the end we come out with the oddly satisfying sensation that we know less about the real T.E. Lawrence than we did going in, which makes us want to revisit Lawrence of Arabia over and over--and why I would never brand it with the moniker of my least favorite genre, a mere bio-pic.

The one downside to telling Lawrence’s story in such a complete, objective and mystifying style, is that it makes the second half of the movie far less exciting and enjoyable than the first half. The first, much longer, part of the film delights, amazes and entertains in ways that actually becomes more and more enjoyable with each subsequent viewing. The better you know the story and the film, the more you excited you get as you anticipate upcoming sequences. Almost everything we see before the intermission depicts Lawrence’s ascent, and his astounding victories and accomplishments, whereas part two concerns the political maneuvers that undid many of his achievements, his failure to win national self-determination for the Arabs and his decent into a kind of madness. But the fact that the second half of Lawrence is not as endless rewatchable as the first doesn’t diminish the film's brilliance. Lesser historical pictures settle for paying lip service or even ignoring the ultimate outcomes of their heroes’ deeds, but Lawrence, better than any other epic, demonstrates how failing to learn from history dooms us to repeat it.

Lawrence also had many lessons to teach audiences and film studios decades after it was made. In the late 1980s, film historian Robert A. Harris undertook a mission to restore the film to its original glory. When it became evident that many of the great movies made during the introduction of large format processes were fading and becoming unwatchable, Harris and his partner Jim Painten, along with high-profile allies like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg, successfully convinced Columbia Pictures to put up the substantial sum required to salvage, repair and fully restore the film’s negative, and to give the restored version a full scale theatrical re-release. Harris, under Lean’s supervision and with help from Anne V. Coats, not only located and reintegrated all the footage that had been cut from the film over the years, he repaired every scratch and blemish on the camera negative, and then generated new prints on modern 70mm film stock.

The restored Lawrence was a huge success when it hit theaters in February of 1989. It created new enthusiasm for classic movies and, at a time when the quality of theaters owned by cinema chains was in a deplorable state, awakened a renewed appreciation for seeing films on big screens in large, well-maintained cinemas. The success of the reissue not only enabled Harris to go on to restore other great films that were in danger of being lost, like Spartacus, My Fair Lady and Vertigo, but it created a sea change in the film industry. Studios saw new value in maintaining their archive of old movies, high-end home video formats came into vogue, and Ted Turner stopped making cheap colorized video versions of his library of old titles, and instead launched cable networks that prided themselves on restoring and presenting these films on television as properly and accurately as possible. Those of us who love cinema history and watching films in theaters owe an immeasurable debt to Lawrence of Arabia, not only because it set the gold standard for historical epics, but also because it reminded us why we love going to the movies in the first place.