George Lucas’ 1977 film Star Wars was the Citizen Kane of my generation. It was the film that made us all want to make films when we grew up. While the sheer spectacle of the movie, its visual shock & awe, and the kinetic energy of its editing were unprecedented at the time of its release, I think the film is still every bit as exciting and rich an experience now as it was in 1977. Like Casablanca and The Wizard of Oz, it represents the best of what film can achieve when all the stars align. It demonstrates the power of the medium to thrill, surprise, and inspire. When viewed in its original, non-Special Edition form, the trilogy stands alone, setting the high bar of creative, commercial, cinematic achievement, next to which all Hollywood output will be forever measured.

Because of its unique status in film history and the fact that it has been endlessly “improved” upon, Star Wars is also the best example of how a great film can take on a life of its own and become more powerful than its writer and director could ever have imagined. Comparing the original Star Wars to its altered versions and insipid prequels demonstrates how the power of cinema extends far beyond the vision of a single individual and their ability to realize that vision. I would go as far as to say that the Star Wars trilogy is a rebuttal to purveyors of the auteur theory who adhere to the idea that film is essentially the work of a single person.

These three films illustrate the ways in which filmmaking is a collaboration, not only of director, actors, craftsmen, and technicians, but also of nature, culture, time, fate, and, above all, audience. Star Wars is a trilogy of great movies, and a cultural phenomenon unlike any other in film history, because of the clear vision and persistence of its creator and all the external conditions that existed at the time of its creation. The Star Wars saga illustrates the heights that can be achieved with the convergence of these varied internal and external factors, which make or, more often, break all movies.

Star Wars is now referred to as, Star Wars: Episode IV, A New Hope, as if this milestone in cinema history could ever be simply an entry in a franchise. Of course, that may have been the original intention of writer/director George Lucas when he set out to make his third feature, after the impressive, dystopian, sci-fi art movie THX-1138 (1971) and the immensely popular, groundbreaking, nostalgic coming-of-age picture American Graffiti (1973). Lucas had a sprawling space opera in his head that was much too large for one movie, so he planned to make his third feature out of the first part of his story and then, if that was successful, make more films later—which, of course, he did.

A major inspiration for Star Wars was the Flash Gordon serials of the early days of cinema when young audiences came to see cliffhanger-style short films told in chapters along with cartoons, newsreels, and feature films. The idea of presenting Star Wars as an episodic adventure series which would begin in the middle with Episode IV, was a brilliant way to establish the style and tone of the picture. Twentieth Century Fox, however, felt this approach would be confusing and did not allow Star Wars to be released with an episode number and sub-title as part of the Flash Gordon-style text scroll that begins the movie. This change was the first one that Lucas made upon his first re-release of the film—and just so you don’t think I’m an ideological purist, it's the kind of change I support.

But Star Wars is not just a big-budget homage to the cliffhangers of old. It’s a modern myth that captured the imagination of an entire culture exactly the way great myths always have. Star Wars is not based on a classic novel or any other type of preexisting property like Flash Gordon. Instead, Lucas drew heavily on the writings of Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with A Thousand Faces, to create a story that was at once original while also being archetypal in its characters, relationships, and structures. People who dislike Star Wars dismiss it as a hodgepodge of clichés, but to do so is a major oversimplification and incorrect dismissal of Lucas's achievement. Although the difference between archetype and stereotype is, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder, I would suggest looking at almost any other film that draws on ancient myths for inspiration (including many made by Lucas, like 1988s Willow) to see the difference between creating something entirely new out of what has come before and simply recycling familiar characters and storylines. While the narrative concepts in Star Wars are as old as the Greeks, it nonetheless created the exhilarating feeling of seeing something entirely new when it was released.

But Star Wars is not just a big-budget homage to the cliffhangers of old. It’s a modern myth that captured the imagination of an entire culture exactly the way great myths always have. Star Wars is not based on a classic novel or any other type of preexisting property like Flash Gordon. Instead, Lucas drew heavily on the writings of Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with A Thousand Faces, to create a story that was at once original while also being archetypal in its characters, relationships, and structures. People who dislike Star Wars dismiss it as a hodgepodge of clichés, but to do so is a major oversimplification and incorrect dismissal of Lucas's achievement. Although the difference between archetype and stereotype is, to some extent, in the eye of the beholder, I would suggest looking at almost any other film that draws on ancient myths for inspiration (including many made by Lucas, like 1988s Willow) to see the difference between creating something entirely new out of what has come before and simply recycling familiar characters and storylines. While the narrative concepts in Star Wars are as old as the Greeks, it nonetheless created the exhilarating feeling of seeing something entirely new when it was released.

Star Wars felt fresh and exciting because it drew on so many different sources to create its universe. In addition to Campbell's writings and the serialized adventures of early movie matinees, Lucas also looked to Japanese cinema for inspiration. Many of Star Wars's mystical and spiritual aspects can be traced to Eastern religion and the samurai code. Also, Star Wars’ basic plot was directly inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s 1958 film The Hidden Fortress, especially the novel conceit of telling the story through the perspective of the film’s lowliest characters. This clever narrative device of Kurosawa’s is even more brilliantly employed in Star Wars. Lucas drops the audience into the middle of a universe and a storyline about which we know nothing apart from what the opening scroll has told us. Following the relatively ignorant characters of two robots, R2-D2 and C-3PO, enables us to enter the world of Star Wars with ease and Lucas to tell the story with then-unprecedented editorial pacing.

Of course, not everyone loved Star Wars when it was released, and even more people dislike it now. Many claim it (along with Steven Spielberg’s Jaws) began the decline of cinema from a true art form to a strictly commercial enterprise. This is a little like blaming Albert Einstein for nuclear warfare. There is no denying that, unlike almost all of his fellow filmmakers who came of age in the 1970s, George Lucas was as good a businessman as he was a storyteller. Star Wars was made on a modest budget, and Lucas’s ability to maintain ownership of his creation and turn the money it generated into his own empire is almost as impressive an accomplishment as the film itself. But I will argue to my last breath with anyone who claims that Star Wars is not a great film.

Lucas wrote a remarkable screenplay. Naysayers will claim that it is full of wooden, arcane dialogue and paper-thin characters. I can’t contend that the dialogue of this picture is on a level with Ben Hecht or David Mamet any more than I can deny that the acting in this film is on the stiff side. But to dismiss a script that creates an entire universe in the imagination of its audience because of some arch or goofy dialogue completely misses the point. Equating great screenwriting with great dialogue is like judging great cooking by how good a meal looks on the plate: it’s important, yes, but what really counts is how the meal tastes. There's a reason why The Writers Guild of America views contributions of dialogue as the least important component of the screenwriting process.

Star Wars proficiently uses exposition, innuendo, and astute borrowing of familiar themes and tropes to create a grand, sweeping universe of imagined worlds and adventures. What the film shows us is incredible, especially to an audience in 1977, but what it hints at is even more epic. In the movie's first scene of actual exposition (which comes a full 32 minutes into the picture), the young hero Luke Skywalker is given his late father’s lightsaber weapon by his mentor figure Obi-Wan Kenobi. Obi-Wan then speaks to Luke about the past, referring to the Old Republic, the Jedi Knights, the Clone Wars, and the Force. When Luke asks how his father died, Obi-Wan delivers a brief monologue, only twenty-five seconds long, in which he explains the events that occurred prior to the story we are now watching.

This scene, which is rendered all the more powerful through the wistful and evocative John Williams underscore, lays out a backstory so rich that, in the imagination of the audience, its potential seems unlimited. This scene provides more than just exposition and explanation.  It is our entry point into the expansive world of Star Wars, a world that could sustain not just two sequels, but also an unlimited amount of books, games, and other media. The dialogue in this scene is not arcane or paper-thin, and the delivery by Alec Guinness is neither wooden nor stiff. This scene fully engages the mind and draws the audience into the film as active participants, which is exactly what we go to the movies for.

It is our entry point into the expansive world of Star Wars, a world that could sustain not just two sequels, but also an unlimited amount of books, games, and other media. The dialogue in this scene is not arcane or paper-thin, and the delivery by Alec Guinness is neither wooden nor stiff. This scene fully engages the mind and draws the audience into the film as active participants, which is exactly what we go to the movies for.

The vast universe suggested by this scene, and many others like it throughout Star Wars, is infinitely more fascinating than the one Lucas shows us in the prequels he made twenty years later. Comparing the original three pictures with the prequels that followed demonstrates the power of well-placed, contextualized dialogue to paint limitless ideas in the mind of a moviegoer and how much more engaging this technique is than using a computer to paint colorful images for a passive audience to watch.

Of course, I can’t blame Lucas for trying to push the technical envelope in those later films. Special effects are another aspect of the original Star Wars that make it so, well, special. Before Star Wars, science fiction was not taken seriously, apart from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, A Space Odyssey and a handful of smaller films. Special effects were not yet viewed as an art unto themselves. What Lucas did for the craft of visual effects is comparable to what Walt Disney did for animation or what Jim Henson did for puppetry. He took an art form that was considered substandard, and primarily for kids, and he reinvented it on a far grander scale, legitimizing it for every kind of audience.

Although Star Wars utilizes all the same basic techniques that were around when The Wizard of Oz was made, Lucas modernized them, made them sophisticated, and gave a new generation of craftsmen the opportunity to build and improve on what had been created 40 years before. The most significant technical breakthrough that resulted from Star Wars was John Dykstra’s invention of motion control. This computer-controlled system allowed a camera to perfectly duplicate moves over and over so it could make identical passes on miniatures, paintings, and scale models for multiple exposures on 65mm film stock. This new technique enabled the effects shots in Star Wars to achieve the same kind of movement through the frame as non-effects shots, and it created an infinitely more dramatic and visceral feel to these types of images.

Motion control, combined with the unequaled skill of the artists and technicians behind the special effects and the rapid editorial style Lucas and his wife, film editor Marcia Lucas (American Graffiti, Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore, Taxi Driver), developed made the film look unlike anything that had come before it. Combat photography was another major inspiration for Lucas, especially 16mm films of aerial dogfighting during World War II. His desire to make his space dogfights as exciting and realistic as real footage taken from inside the cockpits of fighter planes is what drove the innovations in special effects that he pioneered.

Star Wars became one of the most beloved and successful films of all time. Lucas produced two sequels in the early 1980s that not only lived up to expectations but also, in many ways, exceeded them. The general consensus is that the trilogy's second film, The Empire Strikes Back, is an even better movie, but I can’t go quite that far. While the sequel may improve on many of the weaknesses in the original film, it could never be the unprecedented and revolutionary achievement of the first picture, nor does it stand on its own as a fully realized and self-contained narrative. In those respects, Star Wars is one-of-a-kind.

For the follow-up to Star Wars, Lucas wisely turned the screenwriting and directing chores (and the evidence suggests that he did view these jobs as chores) over to others so that he could concentrate on creating and producing the films and building his empire. As if to validate all my convictions about film working best as a collaborative medium rather than the work of a single auteur, The Empire Strikes Back surpassed Star Wars in several major ways. The screenplay was written by Raiders of the Lost Ark scribe, Lawrence Kasdan, who took over from legendary writer Leigh Bracket (The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo, The Long Good-Bye) when she passed away. The screenplay brilliantly follows Lucas’s original storyline while adding humor, character, and much-improved dialogue. For Kasdan, Empire was every bit as much a job for hire as Raiders was, but he proved up to the task in both cases. He was the perfect choice to convey Lucas’s ideas, maintaining and expanding the world that had been created and having a ton of fun running around in it.

The visual effects and sound design also took a major leap forward with this picture, which had a considerably larger budget than Star Wars and even more talent working on it. For the director, Lucas turned to one of his mentors, Irvin Kershner, director of many instalments in popular franchises (including the enjoyable Never Say Never Again, the serviceable The Return of a Man Called Horse, and the quite awful Robocop II). Kershner, Kasdan, and Lucas proved an incredible team. The film works on nearly every level. Even people who don’t like Star Wars have difficulty completely dismissing Empire.

The final film in the Star Wars Trilogy is not as well-loved as the first two, but I consider it a worthy conclusion to this unique series. It suffers a bit from re-treading some of the same ground as the previous two films—the third act of this story is essentially the same as the third act of Star Wars—and it doesn’t quite achieve its predecessors' emotional highs and lows. However, the movie explores and resolves most of the series’ key themes while providing a great deal of cinematic excitement.

Lawrence Kasdan served again as screenwriter with Richard Marquand (Eye of the Needle, Jagged Edge) taking over the direction. Marquand, who died young and is therefore not around to defend himself, is often blamed for the faults of this film, but I think this movie turned out pretty much exactly like what George Lucas wanted. As far as I'm concerned, everything in the picture works. True, it would have been fascinating to see how Jedi would have turned out if Steven Spielberg had been able to direct it, as Lucas originally wanted, or if some of the others who were considered had signed on (such as David Lynch), but Marquand does a fine job with the intentionally more upbeat final chapter in the series. Kasdan believed that the character of Han Solo (played by Harrison Ford) should get killed in this film. Many, including Ford, agreed, and that outcome would have given the picture a level of tragedy and emotional resonance that might have enriched it. But the entire story of Jedi is one of redemption and triumph as much as the story of Empire is one of loss and facing up to unpleasant truths. Those who dismiss the happy ending of this movie are missing the point and should be watching Chinatown instead.

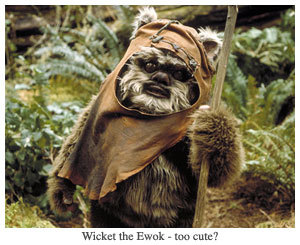

The biggest complaint most fans have about Return of the Jedi is the presence of the Ewoks: fuzzy little bear-creatures that help the heroes achieve victory in the final battle. I concede that they are probably too cute and goofy to succeed as the metaphor for America’s failure in Vietnam that Lucas intended with this climax, in which primitive warriors defeat an enemy with superior technology and funding. But I find the sequences on the Moon of Endor to be entirely consistent with the rest of the action in the Star Wars trilogy, Ewoks and all. The way in which the lighthearted forest fight is intercut with the epic space battle above and the psychological lightsaber duel between Luke Skywalker, Darth Vader, and the Emperor on the Death Star space station add layers of complexity to this climax that match, and sometimes outdo, the endings of the previous two films. In any case, Jedi is nowhere near as condescending and childish as almost everything in the unwatchable Star Wars prequels. It amazes me that some people actually consider this film inferior to the last of the prequels, Revenge of the Sith. Sitting through any of the prequels is like watching someone else play a video game you hate for two hours.

The biggest complaint most fans have about Return of the Jedi is the presence of the Ewoks: fuzzy little bear-creatures that help the heroes achieve victory in the final battle. I concede that they are probably too cute and goofy to succeed as the metaphor for America’s failure in Vietnam that Lucas intended with this climax, in which primitive warriors defeat an enemy with superior technology and funding. But I find the sequences on the Moon of Endor to be entirely consistent with the rest of the action in the Star Wars trilogy, Ewoks and all. The way in which the lighthearted forest fight is intercut with the epic space battle above and the psychological lightsaber duel between Luke Skywalker, Darth Vader, and the Emperor on the Death Star space station add layers of complexity to this climax that match, and sometimes outdo, the endings of the previous two films. In any case, Jedi is nowhere near as condescending and childish as almost everything in the unwatchable Star Wars prequels. It amazes me that some people actually consider this film inferior to the last of the prequels, Revenge of the Sith. Sitting through any of the prequels is like watching someone else play a video game you hate for two hours.

In 1997, George Lucas re-released the Star Wars trilogy in so-called “Special Editions,” which he claimed corrected the “mistakes” he made in the films and enabled him to finally add what was technically impossible to do at the time. What a bunch of shit. This statement implies that the imperfections in Star Wars have to do with its special effects or production values. But no computer could fix the things that are legitimate weaknesses in the movie—you can’t digitally turn Mark Hamill's acting style into that of the young Montgomery Clift.

I consider the act of tinkering with a film after its release to be an unforgivable desecration. I do not accept that it is the right of a film’s creator to change his work just because he wasn’t able to fully realize his original vision. A classic film is much larger and more important than an artist’s intentions. Changing the content of a film after its release is not like remastering a film’s picture, or even remixing its soundtrack. It is not even on the level of creating colorized versions of black-and-white films, or 3D versions of two-dimensional films. Rather, it is tampering with a film’s DNA, its fundamental nature. It’s a Frankensteinian undertaking wherein modern techniques and contemporary social, political, and moral attitudes are infused into something in which they did not and could not organically occur. It creates a domino effect, with each change altering the whole until the entire film is compromised.

Works of art and popular culture should stand as testaments to the time in which they were created so that we can study and learn from them. I think it should be against the Director’s Guild of America code to make these kinds of changes (although I’m sure they would never go for that—the tinkering process furthers the notion that a movie is the creative property of a director). Instead, a great and beloved film belongs to everyone who loves it. As the kids in South Park pointed out, “What would we have if the Beatles updated “The White Album” every few years?” It is a fool's errand to attempt the kind of changes Lucus inflicted on his work, and I think one has to be in a certain kind of denial to look at the altered Star Wars films and think they are improvements. Sure, it may make them more accessible to little kids who prefer the prequels, but those kids will grow up and probably reevaluate their original assessments—just as kids like me who grew up with Roger Moore as James Bond came around to preferring Sean Connery by the time we were fifteen or so. Even if little kids don’t change their minds, are little kids really the audience for whom these films are exclusively intended?

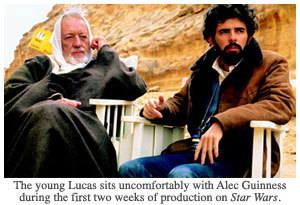

The most drastic changes to Star Wars in the Special Edition occur in the Mos Eisly spaceport sequence. Mos Eisly is an environment which I’m sure Lucas imagined as much more alive with activity than what he shot during his first two weeks of production in Tunisia while dealing with weather delays, equipment failures, and the usual host of problems a major production. But what he did capture feels totally credible, as does every other environment in the first Star Wars film. This palpable sense of a place that has been used and inhabited comes from the fact that these settings were first physically built and then enhanced through groundbreaking editing and through Ben Burtt’s brilliant use of sound design. In the Special Edition, however, Lucas fills the spaceport with digital characters that upstage the main action and remove any semblance of realism the setting once had. It further diminishes Mos Eisly from the dangerous place we’re supposed to believe it is and turns it into a cartoon version of a futuristic town with goofy little characters bumbling around.

One can only imagine what a difficult undertaking it must have been for George Lucas to make the original Star Wars. Apart from Alan Ladd Jr., the head of Twentieth Century Fox, who put up the money, few people believed in the film. It is well-documented that Lucas did not get along with the British crew while shooting the movie. In addition, Industrial Light and Magic, the company he put together to create the special effects, was a dysfunctional group of hippies who generated less than four seconds of usable film after one year and hundreds of tens of thousands of dollars. Even his peers didn’t understand why he wasted time on this kiddy flick. One can view Lucas as a misunderstood genius who made his film despite all the terrible forces arrayed against him. Or one can view him as I do: as a talented and dedicated filmmaker who benefited from all these obstacles placed in his way. The result of all his efforts and setbacks is not a compromised near miss, but one of the greatest and most successful films of all time.

Encountering and overcoming roadblocks is a director's job. Ideas and intentions are a dime a dozen in the world of filmmaking. But a director is not just someone with “a vision.” The skill to find solutions to problems and transform disasters into improvements on an original intention is the essence of directing. The challenges a director faces over the course of bringing a film to fruition are every bit as important to the end result as his original ideas.

Lucas benefited tremendously from the state of the studio system at the time he started making movies. The 1970s were a time of amazing artistic freedom and cinematic experimentation. Films like Bonnie and Clyde, Easy Rider, The Godfather, The Exorcist, The Last Picture Show, and Taxi Driver were revolutionizing the industry and exposing audiences to more personal cinematic experiences. Lucas famously battled with Universal Pictures over the final versions and releases of his first two films. These fights, and the support he got from audiences and critics, were a large part of what enabled him to approach Star Wars as independently as he did and to make the kinds of clever maneuvers that not only got the film made but allowed him to retain ownership of it. The level of artistry the British craftsmen put into the making of a movie (a movie that they apparently didn’t believe in) is a testament to the state of film production practices in England and the importance of their contributions. The incredible sets, costumes, and cinematography created for this picture on its fairly limited budget are the results of a great number of talented individuals. The time and money those hippies spent at Industrial Light and Magic was not a wasted year; it was a year spent inventing the means to achieve the vision Lucas had, and it resulted in the ability to create special effects that still don’t look dated, goofy, or old-fashioned even forty years later.

And let's not forget the contributions of the actors. Lucas is known to have spent months trying to re-voice C-3PO in post-production to make him into the slick, used-car-salesmen-character he had originally envisioned. But he eventually realized that actor Anthony Daniels (who, like many of the English actors, was hired to be the body but not the voice of his character) had created such a strong characterization that to change it would be to diminish it. The result is the fussy English butler robot that became one of the most iconic and best-loved characters in film. For a glimpse at the way things might have been, compare C-3PO with any of the digital characters in the Star Wars prequels—all of whom, I’m sure, turned out exactly the way Lucas envisioned them.

To point out the importance of collaboration in an undertaking as major as Star Wars is not to take anything away from Lucas’ achievement as a visionary filmmaker. However, to compare a movie director to a painter, as Lucas frequently has, is to diminish the contributions of hundreds of artists and reduce them to mere tools that one true artist uses and discards according to his genius whims. A film is not a painting, a piece of sheet music, nor a novel. It is not something that one person can create alone. The invention of digital technology has empowered directors to have more control over their films, but the more directors like Lucas try to turn filmmaking into painting, the smaller and stiffer and less “alive” films become. One only needs to look at the three Star Wars prequels for inarguable proof.

A film is not like a robot that an inventor can build piece by piece. It is more like a child that a parent must raise. It has a life of its own. A director must try to guide that life in the direction he wants, but he can never force it to completely conform to his will, any more than a parent can mold their child like a piece of clay. That road, of course, leads to the Dark Side.

All the changes Lucas made to the original Star Wars trilogy would not be so terrible if he was not trying to remove the films' original versions from the collective memory and replace them with his updated versions. Many of his contemporaries have seen the light and realized the folly in “improving” their earlier works. Steven Spielberg acknowledged his mistake in returning and making changes to his favorite of his films, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, when it was re-released on its 25th anniversary. Five years later for the BluRay, and all of E.T.’s subsequent releases, the film was returned to its original form with the “special edition” not even packaged as a bonus feature. One can only hope that once George Lucas has left this planet, the people to whom he entrusts his legacy will believe that the best way to honor that legacy will be to return his creations to their original form. I have faith that it will happen. A great film is more powerful and more important than the iron will of its creator. And all three Star Wars movies deserve to be regarded as great films.