Independent films were around before the Hollywood studios got created, and they encompass a great variety of styles, stories, and production values. But for the last several decades, when most of us think of an “indie movie,” a certain type of picture and road to release come to mind: a thought-provoking low-budget offering from a free-spirited writer/director with few or no well-known actors shot in everyday settings, that gets screened at film festivals before slowly making its way into the corners of the mainstream, championed by critics and other influencers. These rough parameters do indeed cover a great deal of post-1970s indie pictures. Many film lovers consider the 1990s as the golden age of independent cinema. That was the decade that saw the rise of Sundance and other indie film festivals. It spawned the creation of independent distributors such as Miramax, Good Machine, and New Line Cinema—as well as the indie-wings of the major Hollywood studios like Sony Pictures Classics, Fox Searchlight, Paramount Vantage, and Warner Independent. And the ‘90s was the era that the Oscars began to recognize and award independent pictures on par with major releases, culminating in 1997 when only one Best Picture nominee, Cameron Crowe's Jerry Maguire, was was a major studio release.

For me, however, the ‘90s were simply the time when indie movies became commercialized and more successfully marketed, and it is the 1980s that deserve the distinction of being the true golden age of independent cinema. As in the ‘70s, countless low-budget horror, action, and exploitation pictures were produced, but the new surge in American markets, bringing an increase in available independent financing, also made possible an explosion in production for British, Australian, and foreign-language pictures. Most significantly, the ‘80s formed an era when young, independent writer/directors, often working with meager resources, started making little dramas and comedies that drew attention from a mass audience. It was the decade that gave us the débuts of John Sayles, Tim Hunter, Gus Van Sant, Jim Jarmusch and Sara Driver, James Cameron and Gale Anne Hurd, John McNaughton, Abel Ferrara, Stuart Gordon, Susan Seidelman, Robert Townsend, Wayne Wang, Alex Cox, Allison Anders, Bill Sherwood, the Coen Brothers, Spike Lee, and Steven Soderbergh.

The last two names on that list of iconic ‘80s indie filmmakers were the most influential for me. Spike Lee and Steven Soderbergh not only made two of my all-time favorite movies, they published the diaries they kept while developing, writing, shooting, editing, and releasing those pictures. For a kid dreaming of one day making his own films, watching these movies over and over on VHS and reading the daily details of their creations felt like a personal gift, delivered directly to me from relatable heroes. Though more talented, driven, and clever than I, they were only a little bit older, and they loved what I loved—thus, they inspired me in ways no other filmmakers had before.

Lee and Soderbergh knew how to write for the tiny budgets they assumed they would be limited to. They kept their casts small and their locations few. And they knew they had to explore something provocative if their little films were going to compete with the giant advertising and distribution wings of the majors. Wisely, they both centered their original screenplays on sex—even putting “sex” in their titles (that’s the ostensible “It” in She’s Gotta Have It). But unlike the innumerable independent exploitation pictures that played drive-ins and grindhouses in previous decades, these sexy movies were not to be the kind of titillating, quasi-softcore excuses for showing nude or scantily clad women. These movies explored how the drive and expression of human sexuality can determine and sometimes distort our personalities, actions, and how others define us. These were serious films that could play to erudite, art-house audiences while also being hilarious, compelling, and highly relatable mainstream fare.

Lee’s début picture came out first and is the more quintessential ‘80s indie movie of the two, in that he made this film for very little money in a run-and-gun, guerrilla-style. He served as writer, producer, director, and editor and played one of the main characters. A native New Yorker, Lee learned his craft at NYU grad school from teachers including Martin Scorsese and my own mentor Roy Frumkes. He shot his black & white, super-16mm, eighty-eight-minute feature in just twelve days during the summer of 1985. His budget was $175,000, which he pulled together from small grants, gifts, loans, and deferred payments. Lee even put himself and his lack of resources at the center of the tiny ad campaign he devised, shooting a trailer that opened with him on a street corner selling tube socks as a way to make ends meet and imploring audiences to check out his new film—“Ya gonna go? Ya gonna go? Ya gonna go?” People did go, first to one lone New York theater, which saw lines around the block for every show. Then the movie gained a wider release, eventually discovered by millions on VHS, which is how I first saw it.

She’s Gotta Have It tells the story of Nola Darling, an artistic, professional, attractive Brooklynite in her late twenties, with a liberated attitude towards sex. She is seeing three men: the sweet and stable Jamie; the gorgeous but self-obsessed Greer; and the playfully goofy Mars. Nola loves elements of each guy but is not in love with any of them. She isn’t looking for love, and therefore she refuses to commit to any of her lovers when they each demand to have her for himself. All three men, in their own distinct ways, psychoanalyze Nola with their pet theories about why she needs so much sex. Most of these assumptions turn out to be wrong, and we come to see that Nola is simply a healthy, mature woman who is both in touch and at peace with most aspects of her life, including her sex life.

Lee, a prolific screenwriter all through college and graduate school, began with the title. The ‘80s were perhaps the last years when producers began a project with little more than a marketable title. The practice is often derided for being too commercially minded, but it is, in fact, an excellent way for a small-timer to start writing a feature that could actually get people to go out and buy a ticket. She’s Gotta Have It sounded a little like a porno movie, and it got people laughing when Lee would say it was the title of his next project. It also made it difficult to approach certain actors, grantmakers, and owners of locations he hoped to shoot in, as many thought it sounded like a dirty movie or a film that denigrated women. But Lee believed the provocative title was key to getting across what he most wanted to explore—the cultural double standard that encourages men to pursue and enjoy sex with multiple partners but shames women who engage in the same behavior.

He filled his diary with ideas about the way he wanted his film to look and the type of sexy movies he did not want it to end up like. He began researching the project by talking to female friends. Listening to their experiences, he was shocked to learn how many women he knew had had more than a hundred lovers by the time they were in their mid-twenties. He also immersed himself in literature written by black female authors like Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Sonia Sanchez, and Zora Neale Hurston. Always adamant about making black films for black audiences, Lee was determined to write and cast as his lead a beautiful dark-skinned woman, who loved sex but who was not the “freak” that many man and women labeled her.

He quickly came up with her name, Nola Darling. Being a man, and a young man at that, Lee felt he didn’t know enough about women to write Nola with any depth or authenticity. To make Nola “real,” he and a couple of women friends created a forty-question survey that Lee planned to put to a diverse group of black women. He was surprised to find over women who agreed to respond to these intimate inquiries and allow Lee to record their interview sessions. These were audiotapes, not videotapes, but the types of questions he devised were not all that dissimilar to the interviews the James Spader character in sex, lies, and videotape asks the women he records: questions about their sexual experiences, preferences, boundaries unwilling to cross, and fantasies too extreme to ask for.

Lee had the young stage actress Tracy Camilla Johns in mind for Nola from the get-go. He knew her from his student film days and believed she would respond well to the character and the themes of the story. She fit the bill in terms of being a beautiful, dark-skinned black woman. Lee also knew her as someone completely comfortable with her body and with the way men reacted to her physically. He sent her his earliest screenplay drafts for her notes and feedback, and she was the first actor to commit to the picture.

Lee then concentrated on the three men Nola is involved with, as well as two female supporting characters—Nola’s former roommate, who moved out because of the constant stream of guys in their apartment, and a lesbian friend who pursues Nola as fervently as any of the men. Lee cast Tommy Redmond Hicks, one of the stars of his NYU thesis film, Joe's Bed-Stuy Barbershop: We Cut Heads (1983), as Jamie Overstreet, the most romantic of Nola’s lovers. For the role of the vain Greer Childs, Lee pursued Eriq La Salle, a graduate of Juilliard and NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts who was then an up-and-coming leading man. But before She’s Gotta Have It was ready to start, La Salle had joined the Screen Actors Guild, barring his participation in the non-union, micro-budget production. Lee went with John Canada Terrell, who does an excellent job as the image-obsessed, arrogant Greer, whom Nola dates simply because of how good he is in bed.

For her third lover, the diminutive B-Boy Mars Blackmon, Lee made the unusual choice of casting himself. In some ways, this step was logical in that it meant one fewer actor for him to have to pay, schedule around, and develop a directorial rapport with. As a director already juggling so many other responsibilities, the fact that Lee would also have to concentrate on his own look and performance made some of his collaborators wary that playing Mars would be one hat too many to wear. But the ultra-confident Lee felt that if Woody Allen could do it why couldn’t he? Additionally, The multi-talented Ernest Dickerson, a cinematographer who had come up through NYU grad school with Lee and had shot all his student films, was to photograph She’s Gotta Have It. The two had developed a comfortable, symbiotic working relationship. Without any issues of pride, protocol, or creative authority getting in the way, Dickerson was able to step into the role of director when Lee was in front of the camera.

Lee’s performance as Mars turned out to be one of the highlights of the movie. The character is so funny he’s almost single-handedly responsible for the dramatic film being viewed as a comedy. This element of laugh-out-loud humor was surprising to most people because Lee, unlike Mars, is a deeply serious, driven, politically motivated artist—not the kind of person anyone considered the funniest guy in the room. Mars, on the other hand, is a wild, uninhibited goofball whose only passions outside of women are basketball and hip-hop. Lee, Dickerson, and costume designer John Michael Reefer went out of their way to accentuate Lee’s less than flattering physical attributes in the way they photographed and dressed Mars. Lee shaved off his facial hair and got a short, fade-style haircut. He wore oversized, thick-rimmed glasses and shot Mars’s close-ups with a wide-angle lens that made him look all the more ridiculous when he leaned into the camera. In addition to his treasured Nike sneakers and the chain around his neck that spelt out MARS in gold lettering, he dressed in short shorts that highlighted his skinny legs and elfin frame. In wide shots where Mars stands next to Nola, she towers over him making their coupling seem all the more comical. But, of course, Nola is involved with Mars specifically because he makes her laugh.

Mars Blackmon turned out to have a life beyond She’s Gotta Have It, appearing in several Nike TV commercials (which Lee directed) with Mars’s hero Michael Jordon, and introducing RUN-DNC on Saturday Night Live. He became a kind of alter ego for Spike Lee.

Lee is a filmmaker who draws heavily from both classic and contemporary cinema when creating his own style. The structure of She’s Gotta Have It was influenced by Akira Kurosawa's iconic Rashomon (1950), in which various characters provide subjective and contradictory versions of the story, and by Warren Beatty's then-recent epic biopic Reds (1981), in which interviews with real-life "witnesses" are employed to help convey and contextualize the historical drama. Lee eschewed realism in favor of a highly stylized approach that would be easy to do on a shoestring budget and that would also stand out from the crowd, as the French New Wave icon Jean-Luc Godard's influential first feature Breathless (1960) had done.

Lee wrote his script as if it were part a documentary about Nola Darling told in the past tense by the people who knew her, and part a traditional, present tense drama told from her perspective. And in his shooting, he pulls from classic Hollywood, the European new wave, and avant-garde cinema. The documentary techniques—such as interviews with the characters and still photographs that establish the time, place, and milieu—are blended with realistic, dramatic scenes and imagined comical interludes, like the classic “dog sequence” in which we see a rogues gallery of men Nola has had to endure and hear the hilariously bad pick-up lines they tried on her. Most of the movie is shot in black & white, but at one point it switches to rich full color for a choreographed dance number. All of the parts are held together with a sonorous jazz score composed by Spike’s father, renowned bassist Bill Lee.

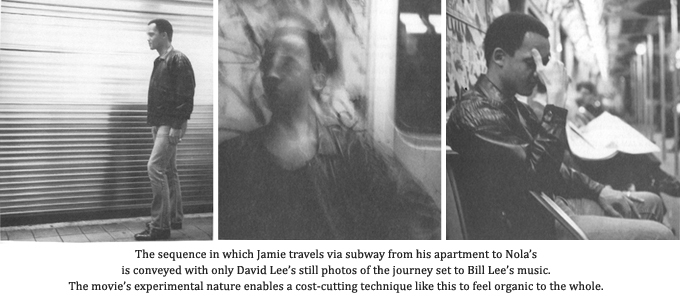

The film utilizes evocative still photography to accomplish several tasks. The opening photomontage of people and places in Brooklyn establishes the neighborhood (both its look and its ethnicity) where the story takes place. A later photomontage indicates the passing of seasons from the hot summer to the cold, snowy winter. A sequence of Nola working in her apartment with quick still images of her art, provides illuminating exposition into her creative life, how she makes her living, and why she lives in a big loft space. At one point, when Nola calls Jamie late at night and asks him to come over, Jamie’s subway trip is conveyed with artistically blurred photos of the actor riding the train—something easy to create without the insurance and permits that would have been required when shooting with 16mm film equipment on the subway.

This quick-and-dirty, experimental approach and Lee’s willingness to try seemingly anything not only made his first feature economically viable, but the unique combination of styles is part of what gives the picture its vitality. Lee went on to be a director who always draws attention to his filmmaking and who reminds us that we are watching a movie. While these traits can be pretentious and distracting in his later work, they feel utterly of a piece with his subject in She’s Gotta Have It. American movie and TV audiences in the mid to late ‘80s were not used to seeing stories about middle-class blacks living ordinary lives free of guns, drugs, and violence; and as we watch Lee’s film it is appropriate to be asking ourselves why that is. It’s thematically relevant that as we watch the picture we’re constantly reminded of who made it and why it had to be done on such a low budget. Lee and Dickerson’s exploration of the sensuality of African-American skin tones was also something unseen in American movies up to that point, and it remained rare for most of the next thirty years.

She’s Gotta Have It became arguably the most groundbreaking American independent film of all time. Not only epitomizing and launching (along with Jim Jarmusch's Stranger Than Paradise) the American Indie movement of the ‘80s, it transformed African-American cinema in ways that pioneers like Charles Burnett (Killer of Sheep), Gordon Parks (Shaft), Melvin Van Peebles (Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song), and even Sidney Poitier (Uptown Saturday Night) hadn’t done. After countless decades of Hollywood and indie filmmakers depicting black people as servants, killers, dopers, stick-up men, pimps, and whores, Lee delivered an intelligent, accessible comedy about the everyday emotional lives of urban, professional people of color. It was celebrated by a wide range of audiences in and outside of America.

While Lee fully acknowledges the importance of his début feature—not only to his career but also to the history of cinema—he is not a big fan of it. Perhaps, like many directors looking at their early work, he only sees the flaws and the things that now embarrass him. But Lee should never feel anything but pride about She’s Gotta Have It—not only for the intelligence and insightfulness of the writing, the playfulness of the filmmaking, the iconic stature of some of the characters but also for the raw, “by any means necessary” nature of the production. She’s Gotta Have It works, at least in part, because of, not in spite of, the humble, youthful, “broke-ass” qualities that infuse every frame. The movie radiates with the unbounded energy and rule-breaking bravado of a young filmmaker setting out to both make a name for himself and change how his people are depicted and treated by one of the most significant, and opinion-shaping industries in America. He succeeded on both counts. She’s Gotta Have It would not have been as good if made by an experienced filmmaker with a large budget. For proof, one need look no further than Lee’s remake of the movie as a ten-episode Netflix series in 2017.

At that time, Lee set out to update his story for a new generation. He embraced the feminist aspects of the premise and hired many female writers to pen episodes. Unfortunately, however, the Nola Darling of the 2017 She’s Gotta Have It is a far cry from the self-possessed, free-spirited, independent woman of the 1986 version. The updated Nola Darling veers cringingly close to the stereotype of a winey, self-absorbed, and entitled millennial. Most of the other characters, especially Nola’s three lovers, are bland and insignificant. (Jamie and Greer are somewhat interchangeable in this version.) The reimagined She’s Gotta Have It, like so many remakes, maintains the basic ideas of the original story but contains none of its revolutionary and revealing power.

Unlike Spike Lee, Steven Soderbergh worked with experienced producers when making his first indie feature. With their help, he secured a cast of established actors and a $1.2 million budget. In his published diary he lays out how he grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where, as a teen, he made Super 8 and 16mm home movies. Rather than going the film school route, he moved to Los Angles to pursue professional filmmaking, working at a series of industry-related jobs ranging from cue card holder, to copywriter, to game show editor and composer. He edited a music video for the band Yes, who was so happy with his work they invited him to edit the concert video they planned in conjunction with their 9012Live tour. When Soderbergh turned them down, they countered with an offer to direct the project and he accepted—snagging a Grammy Award nomination for Best Music Video, Long Form, for the piece. All this time he was writing screenplays on spec and for hire, and making small, experimental films in black and white 16mm.

After several disappointing stops and starts, Soderbergh moved back to Baton Rouge and wrote a screenplay he had been thinking about for over a year. He was surprised by the enthusiastic response from everyone he showed the script to, including several experienced producers. They encouraged him to reconsider shooting the movie for a micro-budget in black and white with a cast of unknowns, as he’d been planning, and to send it out to established, up-and-coming actors. But first, he had to commit to the only title anyone thought was any good. Various drafts went under several pretentious or silly titles such as 46:02, Retinal Retention, Charged Coupling Device, Mode: Visual, and Hidden Agendas. But all his readers felt the only halfway decent option he’d come up with was Sex, Lies, and Videotape (the eventual lead producer Robert Newmyer suggested the use of all lowercase letters).

It’s difficult to overestimate how critical the selection of this title was. Readers of this blog are all too aware of my rants about the longstanding trend of saddling movies with forgettable, interchangeable, single-word titles. Well, here’s a prime example of how a title can make a little film into a cultural phenomenon. Does anyone really think this picture would have become what it became had it not been given such a tantalizing and descriptive moniker? sex, lies, and videotape suggests something intimate, deceitful, and contemporary, intermingled in a potentially sinful combination. The title engenders a provocative curiosity while at the same time it literally states exactly what the movie is about.

The plot of Soderbergh’s film revolves around four outwardly functional but inwardly dysfunctional people: a sexually repressed housewife, Ann Bishop Mullany; her lawyer husband, John; her bartender sister Cynthia, who is having an affair with John; and John’s college buddy, Graham Dalton, who has come to town for a visit. Graham turns out to be a different guy than either John remembers or Ann expects. He has developed a novel way of channeling his sexual desires and preventing the dishonesty and harm he believes all intimate relationships eventually engender. Graham’s presence disrupts the lives of the three other characters in a profound way.

Soderbergh uses the consumer video camcorder, by then a commonplace yet still somewhat novel piece of technology, to explore how people distanced themselves from each other. Graham needs the separation that a video recording provides to allow himself to react purely to another person without worrying about any potential ramifications that could result from his feelings or behavior. Graham’s reserve, his perceived commitment to honesty, and his unusual ways of navigating the world make him fascinating to Ann and to an audience. Most of us, as viewers, see elements of ourselves in all four of the main characters in sex, lies, and videotape, which is part of why the film succeeds on so many levels with such a broad audience.

Soderbergh and his producers Newmyer, John Hardy, and Nancy Tenenbaum sent the script out to both rising and established stars such as Tim Daly, David Duchovny, David Hyde Pierce, Brooke Shields, and Jennifer Jason Leigh. Most name actors were reluctant to work with an untried director. Many agents of actresses refused to even look at a script they assumed would be pornographic. Soderbergh had written the role of Ann with Elizabeth McGovern (Once Upon a Time in America, Racing with the Moon, She's Having a Baby) in mind. But McGovern’s agents refused to even show her a script called sex, lies, and videotape. Theater and TV actress Laura San Giacomo, who would end up playing Cynthia, was represented by the same agency. She got ahold of the script, loved it, and was desperate to get cast in it, but her agents and manager warned her that it would end her career. When his first choice for Cynthia, Jennifer Jason Leigh, signed on to star in George Armitage's fantastic, if little seen, Miami Blues, Soderberg worked hard with San Giacomo’s people to sign the relative unknown, and she became the first actor attached to the project. San Giacomo’s casting was fortuitous for the film and the actress, as Leigh’s star power might have overwhelmed the rest of the ensemble, and sex, lies, and videotape launched San Giacomo as star of the big and small screen. In addition to being a compelling ingénue, the native New Yorker quickly and adeptly adopted a Southern accent similar to that of Andie MacDowell, who would eventually play the lead sister.

When MacDowell, a fashion model turned actress, read sex, lies, and videotape she instantly connected with the material. While her own persona and life experience differed greatly from the character of Ann Bishop Mullany, MacDowell had grown up around women just like Ann. She knew them and, more importantly, she understood them. She didn’t see Ann as a stereotypical prissy, bored, beautiful-but-frigid Southern housewife, but rather as a complex individual wrestling with issues she felt were impolite to speak of or even think about. But MacDowell’s only acting experience had been a small part in the brat-pack showcase St. Elmo's Fire (1985) and her infamous debut as Jane in the highbrow, award-seeking picture Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984).

Soderbergh was reluctant to cast MacDowell based on what he knew of her work, but when she came in to audition she knocked him out with her interpretation. He was convinced no one else should even be seen for the part. His producers feared the first time director had simply fallen for the model’s stunning looks. When he brought her back for another audition for all the producers, she delivered the same solid reading, and she was given the part that rescued her reputation and set the course for her decades-long acting career.

There were several false starts, with money and with some casting falling apart at the last minute, as is par for the course on any independent production. But when Soderbergh landed James Spader—the former teen bad-boy of Tuff Turf, Pretty in Pink, and Less Than Zero, who had recently graduated to dark adult roles in films like Wall Street and Jack's Back—momentum built. Spader also suggested Peter Gallagher for the role of John. Gallagher (The Idolmaker, Summer Lovers, High Spirits) was an inspired choice, as he was able to find humor and personality in the least dimensional of the four main roles.

While Soderbergh conceded to shoot the picture in color, he insisted on filming in Baton Rouge, believing the story needed to take place far away from Los Angeles or any other movie-oriented city. He hired cinematographer Walt Lloyd (Down Twisted), one of the only directors of photography who would consider working with a crew of the director’s friends rather than a team of his own choosing. By all accounts, the making of sex, lies, and videotape was a pleasant, stress-free affair, unlike the experience of most low-budget features. The cast and crew enjoyed their brief time working with Soderbergh, and then they all went off to other projects, leaving the director in Baton Rouge to begin editing his film. Soderbergh cut the feature on a ¾-inch video system, used mainly for editing TV news, which was available to him at his friend Larry Blake’s local sound editing facility. Soderberg and Blake worked happily on the picture and sound edit respectively, with little pressure to meet a deadline.

Soderbergh submitted the finished feature to what was then called the Utah/US Film Festival or the “Park City” film fest, of which Robert Redford was the chairman. One of Soderbergh’s many early industry side-hustles had been as a limo driver for that festival in past years, and he returned in 1989 as both a driver and a director with a film in competition. With his thin frame and reserved demeanor, he cut an unimpressive figure while introducing his little picture to festival attendees. But when the screening ended, audiences leapt to their feet. sex, lies, and videotape did not win the Grand Jury Prize—Nancy Savoca’s True Love took that top honor—but it received the Audience Award and, more importantly, it sold to Miramax pictures, a new independent releasing company started by Bob and Harvey Weinstein.

The Weinsteins brought sex, lies, and videotape to the Cannes Film Festival, where it was booked to play the Directors' Fortnight, Cannes' showcase for up-and-coming filmmakers. Through a twist of fate, a feature dropped out of the main competition’s slate, and sex, lies, and videotape was selected to take its place. Soderbergh foresaw a backlash around this last-minute upstart entering the competition at the venerated festival. But to his surprise, the movie took home the Best Actor award for Spader and the Palme D'Or for himself, making Soderbergh the youngest winner of the festival’s most coveted prize.

One of the pictures edged out by sex, lies, and videotape was Spike Lee’s third feature, Do The Right Thing, which I maintain was the best picture of 1989. Critic Roger Ebert claimed that if Lee’s masterpiece didn’t win the Palme D'Or he would never attend Cannes again, a statement he quickly walked back after the ceremony. One of the pictures edged out by sex, lies, and videotape was Spike Lee’s third feature, Do The Right Thing, which was favored to win and which I maintain was the best picture of 1989. Critic Roger Ebert claimed that if Lee’s masterpiece didn’t win the Palme D'Or he would never attend Cannes again, a statement he quickly walked back after the awards ceremony.

Lee felt blindsided when his highly acclaimed film won no awards, but focused his ire not on Soderbergh’s last minute entry but on that year’s jury president, renowned German filmmaker Wim Wenders. Jurist Sally Field confided in Lee that Wenders found his character Mookie from Do The Right Thing to be “unheroic,” which Lee considered an absurd statement. But even Lee, and the many others who didn’t think sex, lies, and videotape worthy of Cannes’ highest honor, did not dispute its value or Soderbergh’s accomplishment.

Both Soderbergh and Lee had tapped into the zeitgeist the way only a few films each decade ever can—and these two 1989 releases never lost any of their cultural relevance over the intervening decades. Lee’s theme of racial tension heating up to an explosive breaking point foreshadowed the 1991 beating of African-American motorist Rodney King by white LAPD officers and the riots that resulted when those police officers were found not guilty of using excessive force against King. Thirty years later, Do The Right Thing is every bit as timely, tragic, and powerful as it was in 1989, illuminating an institutionalized system of racism and oppression that has been part of our culture since the birth of the United States and will continue to divide us until we fully deal with worst aspects of our history.

On first look, sex, lies, and videotape would seem to have been centered on something far less foundational to our society, the inventive use of a technologic fad. But Soderbergh’s film ended up foretelling the way much of humanity would soon use video technology to connect and distance ourselves from each other. Until this time, though consumer video cameras were becoming commonplace in American homes, and their voyeuristic nature made them a natural subject for cinema, we rarely saw them in movies, let alone seeing a film that revolved around one. But cameras would soon inundate and fundamentally change culture. Not long after sex, lies and videotape screened at Cannes, former teen heartthrob Rob Lowe became embroiled in a scandal involving a homemade video of him engaged in a sex act with a minor—the first of dozens of celebrity “sex-tape” scandals that would become a fixture of the ‘90s. Just one year after Lowe’s potentially career-ending home video became national news, he starred with James Spader in the well-reviewed Curtis Hanson/David Koepp thriller Bad Influence. In it, Lowe’s bad-boy Alex teaches Spader’s milquetoast Michael to be an assertive risk-taker, even at one point, as a dark practical joke, videotaping Michael having sex.

In 1989 it would have been impossible to imagine a world where everyday people of all ages send snapshots of their genitalia to people they’ve just met, or where watching videos of strangers having sex would be considered preferable by large swaths of the population to actually engaging in the physical act of love with another human being. Yet when we revisit sex, lies and videotape with modern eyes, its subject matter seems as contemporary as any current release.

The profound impact of sex, lies, and videotape reaches beyond its ability to capture the mood and preoccupations of its era. The Weinsteins capitalized on the prestigious Cannes win and ran with it, expanding their plans for a limited art-house circuit release and instead putting the little feature into suburban theaters and multiplexes all over the country. The film returned $25 million off its $1.2 million budget, making it more profitable than the year’s biggest grossing studio hit, Batman.

The potential for millions in revenue on a single indie movie transformed the industry and made the Utah/US Film “Park City” Festival (with its name changed in 1992 to the Sundance Film Festival) into an industry event. Sundance became, like Cannes, every bit as much a film market as a film festival. Prior to ‘89, “Park City” was a showcase for movies from underrepresented groups, with a strong contingent of queer cinema, feminist cinema, and experimental cinema, combined with small-scale but prestige studio pictures that needed an extra boost. Other major forces in the indie world had gotten a commercial boost from this festival. The Coen brothers and Jim Jarmusch had launched their careers there five years prior with Blood Simple and Stranger than Paradise. But 1989 was the first time the festival had gotten a commercial boost from a film. And while there had been a market for indie films before 1989, sex, lies, and videotape made this type of picture an industry unto itself.

This restructuring of the film industry resulted in many pros and cons, but I don’t hold the downstream effects of a picture as deservedly successful as sex, lies, and videotape responsible for the changes to cinema it indirectly provoked, any more than I hold Jaws and Star Wars responsible for what they begat. However, these extra-textural elements do make this tiny little film all the more fascinating. What’s most impressive is that the movie holds up so well many decades later. Rather than being a quaint glimpse into how people of a bygone era were affected by a technological fad, the themes Soderbergh introduced are all the more relevant to our contemporary, social-media obsessed, online porn-addicted, infinitely connected yet profoundly disconnected society.

Steven Soderbergh and Spike Lee were both filmmakers ahead of their time but with radically different approaches to their chosen medium. Soderbergh remains a reserved student of human behavior who approached his subject matter almost like an alien anthropologist. Lee remains an in-your-face participant who aggressively pointed out everything he saw that was beautiful, hilarious, underrepresented, unfair, and otherwise worthy of paying attention to. And their careers followed similar paths—both achieving mainstream success with major studio pictures yet frequently returning to their indie roots to make tiny, low-budget experimental features. But whereas Lee seems like he’ll be making films until he drops dead, as if trying to compensate for all the filmmakers of color that came before him who never got the opportunity to create a half-century-long legacy of work, Soderbergh has often toyed with retiring from filmmaking. He claims that there is nothing new to be discovered in the medium (though he seems to constantly undermine that conclusion). I can’t say I’ve loved everything these two titans of indie cinema have done as much as the films that first put them on the map. But I will always make a point to see their latest work, and I still return again and again to their début features and to the perennially inspiring books they wrote about their experiences making those industry-changing movies.